Paganism is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. In the time of the Roman empire, individuals fell into the pagan class either because they were increasingly rural and provincial relative to the Christian population, or because they were not milites Christi. Alternative terms used in Christian texts were hellene, gentile, and heathen. Ritual sacrifice was an integral part of ancient Graeco-Roman religion and was regarded as an indication of whether a person was pagan or Christian. Paganism has broadly connoted the "religion of the peasantry".

Wicca is a modern pagan syncretic religion. Scholars of religion categorize it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and was introduced to the public in 1954 by Gerald Gardner, a retired British civil servant. Wicca draws upon a diverse set of ancient pagan and 20th-century hermetic motifs for its theological structure and ritual practices.

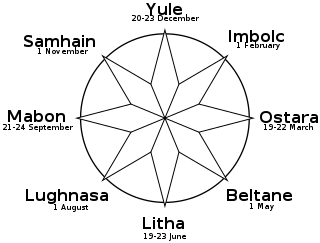

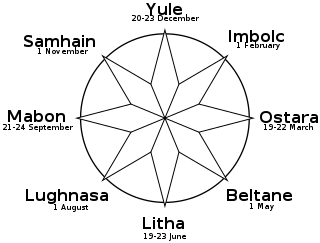

The Wheel of the Year is an annual cycle of seasonal festivals, observed by many modern pagans, consisting of the year's chief solar events and the midpoints between them. While names for each festival vary among diverse pagan traditions, syncretic treatments often refer to the four solar events as "quarter days", with the four midpoint events as "cross-quarter days". Differing paths of modern paganism may vary regarding the precise timing of each celebration, based on such distinctions as lunar phase and geographic hemisphere.

Ukko, Äijä[ˈæi̯jæ] or Äijö[ˈæi̯jø], parallel to Uku in Estonian mythology, is the god of the sky, weather, harvest and thunder in Finnish mythology.

Ár nDraíocht Féin: A Druid Fellowship, Inc. is a non-profit religious organization dedicated to the study and further development of modern Druidry.

Traditional Sámi spiritual practices and beliefs are based on a type of animism, polytheism, and what anthropologists may consider shamanism. The religious traditions can vary considerably from region to region within Sápmi.

Finnish paganism is the indigenous pagan religion in Finland and Karelia prior to Christianisation. It was a polytheistic religion, worshipping a number of different deities. The principal god was the god of thunder and the sky, Ukko; other important gods included Jumo (Jumala), Ahti, and Tapio. Jumala was a sky god; today, the word "Jumala" refers to all gods in general. Ahti was a god of the sea, waters and fish. Tapio was the god of forests and hunting.

The Finno-Samic languages are a hypothetical subgroup of the Uralic family, and are made up of 22 languages classified into either the Sami languages, which are spoken by the Sami people who inhabit the Sápmi region of northern Fennoscandia, or Finnic languages, which include the major languages Finnish and Estonian. The grouping is not universally recognized as valid.

Profanity in Finnish is used in the form of intensifiers, adjectives, adverbs and particles. There is also an aggressive mood that involves omission of the negative verb ei while implying its meaning with a swear word.

The sky often has important religious significance. Many religions, both polytheistic and monotheistic, have deities associated with the sky.

Finland is a predominantly Christian nation where 66.6% of the Finnish population of 5.5 million are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (Protestant), 30.6% are unaffiliated, 1.1% are Orthodox Christians, 0.9% are other Christians and 0.8% follow other religions like Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, folk religion etc. These statistics do not include, for example, asylum seekers who have not been granted a permanent residence permit.

The Mari religion, also known as Mari paganism, is the ethnic religion of the Mari people, a Volga Finnic ethnic group based in the republic of Mari El, in Russia. The religion has undergone changes over time, particularly under the influence of neighbouring monotheisms. In the last few decades, while keeping its traditional features in the countryside, an organised Neopagan-kind revival has taken place.

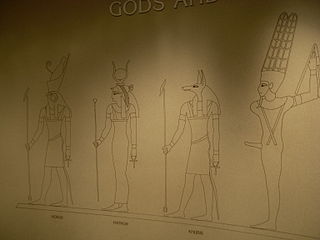

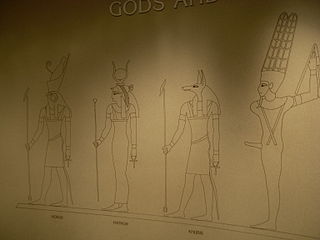

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the belief in a singular God who is, in most cases, transcendent. In religions that accept polytheism, the different gods and goddesses may be representations of forces of nature or ancestral principles; they can be viewed either as autonomous or as aspects or emanations of a creator deity or transcendental absolute principle, which manifests immanently in nature. Polytheists do not always worship all the gods equally; they can be henotheists, specializing in the worship of one particular deity, or kathenotheists, worshiping different deities at different times.

Maavalla Koda is a religious organisation uniting adherents of the two kinds of Estonian native religion or Estonian Neopaganism: Taaraism and Maausk.

Estonian Neopaganism, or the Estonian native faith, is the name, in English, for a grouping of contemporary revivals of the indigenous Pagan religion of the Estonian people.

Druidry, sometimes termed Druidism, is a modern spiritual or religious movement that promotes the cultivation of honorable relationships with the physical landscapes, flora, fauna, and diverse peoples of the world, as well as with nature deities, and spirits of nature and place. Theological beliefs among modern Druids are diverse; however, all modern Druids venerate the divine essence of nature.

Uralic neopaganism encompasses contemporary movements which have been reviving or revitalising the ethnic religions of the various peoples who speak Uralic languages. The movement has taken place since the 1980s and 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and alongside the ethnonational and cultural reawakening of the Finnic peoples of Russia, the Estonians and the Finns. In fact, Neopagan movements in Finland and Estonia have much older roots, dating from the early 20th century.

Caucasian Neopaganism is a category including movements of modern revival of the autochthonous religions of the indigenous peoples of the Caucasus. It has been observed by scholar Victor Schnirelmann especially among the Abkhaz and the Circassians.

Karhun kansa (Finnish: ['kɑrhun ˈkɑnsɑ] is a religious community based on indigenous Finnish spiritual tradition. The community was officially recognized by the Finnish state in December 2013. "Karhun kansa" is Finnish for "People of the Bear". The bear, known as Otso, is the most sacred animal in the Finnish spiritual tradition, and said to be the mythical ancestor of all humankind. Karhun kansa is part of Suomenusko, the contemporary revival of pre-Christian polytheistic ethnic religion of the Finns. Some members of Karhun kansa call their faith 'väenusko' rather than 'suomenusko'. The first part of the term 'väenusko' stems from a Finnish word 'väki', which refers to people, and also both unseen and visible powers that are part of traditional Finnic mythology.