The Vincennes porcelain manufactory was established in 1740 in the disused royal Château de Vincennes, in Vincennes, east of Paris, which was from the start the main market for its wares.

Chinese export porcelain includes a wide range of Chinese porcelain that was made (almost) exclusively for export to Europe and later to North America between the 16th and the 20th century. Whether wares made for non-Western markets are covered by the term depends on context. Chinese ceramics made mainly for export go back to the Tang dynasty if not earlier, though initially they may not be regarded as porcelain.

"Blue and white pottery" covers a wide range of white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration is commonly applied by hand, originally by brush painting, but nowadays by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. The cobalt pigment is one of the very few that can withstand the highest firing temperatures that are required, in particular for porcelain, which partly accounts for its long-lasting popularity. Historically, many other colours required overglaze decoration and then a second firing at a lower temperature to fix that.

Hard-paste porcelain is a ceramic material that was originally made from a compound of the feldspathic rock petuntse and kaolin fired at very high temperature, usually around 1400 °C. It was first made in China around the 7th or 8th century, and has remained the most common type of Chinese porcelain.

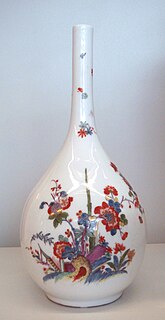

The manufacture nationale de Sèvres is one of the principal European porcelain manufactories. It is located in Sèvres, Hauts-de-Seine, France. It is the continuation of Vincennes porcelain, founded in 1738, which moved to Sèvres in 1756. It has been owned by the French crown or government since 1759, and has always maintained the highest standards of quality. Almost immediately, it replaced Meissen porcelain as the standard-setter among European porcelain factories, retaining this position until at least the 19th century.

Chinese ceramics show a continuous development since pre-dynastic times and are one of the most significant forms of Chinese art and ceramics globally. The first pottery was made during the Palaeolithic era. Chinese ceramics range from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or kilns, to the sophisticated Chinese porcelain wares made for the imperial court and for export. Porcelain was a Chinese invention and is so identified with China that it is still called "china" in everyday English usage.

Plymouth porcelain was the first English hard paste porcelain, made in the county of Devon from 1768 to 1770. After two years in Plymouth the factory moved to Bristol in 1770, where it operated until 1781, when it was sold and moved to Staffordshire as the neucleus of New Hall porcelain, which operated until 1835. The Plymouth factory was founded by William Cookworthy. The porcelain factories at Plymouth and Bristol were among the earliest English manufacturers of porcelain, and the first to produce the hard-paste porcelain produced in China and the German factories led by Meissen porcelain.

Jean-Baptiste Régis was a French Jesuit missionary in imperial China.

Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare was a Jesuit missionary to China. Born in Cherbourg, he departed for China in 1698, and worked as a missionary in Guangxi.

Jean-Baptiste Du Halde was a French Jesuit historian specializing in China. He did not travel to China, but collected seventeen Jesuit missionaries' reports and provided an encyclopedic survey of the history, culture and society of China and "Chinese Tartary," that is, Manchuria.

China–France relations, also known as Sino-French relations or Franco-Chinese relations, refers to the interstate relations between China and France.

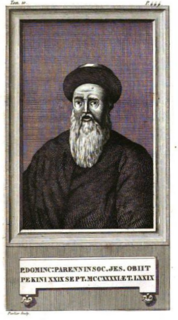

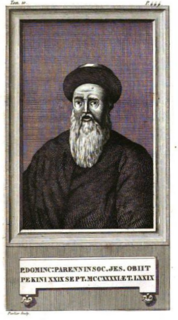

Dominique Parrenin or Parennin巴多明 was a French Jesuit missionary to China.

Dehua porcelain, more traditionally known in the West as Blanc de Chine, is a type of white Chinese porcelain, made at Dehua in the Fujian province. It has been produced from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to the present day. Large quantities arrived in Europe as Chinese export porcelain in the early 18th century and it was copied at Meissen and elsewhere. It was also exported to Japan in large quantities.

Dong'e County falls under the jurisdiction of Liaocheng Prefecture-level city, in the Shandong Province of China. It is located on the left (northern) bank of the Yellow River, some 100 km (62 mi) upstream from the provincial capital Jinan.

Jingdezhen porcelain is Chinese porcelain produced in or near Jingdezhen in southern China. Jingdezhen may have produced pottery as early as the sixth century CE, though it is named after the reign name of Emperor Zhenzong, in whose reign it became a major kiln site, around 1004. By the 14th century it had become the largest centre of production of Chinese porcelain, which it has remained, increasing its dominance in subsequent centuries. From the Ming period onwards, official kilns in Jingdezhen were controlled by the emperor, making imperial porcelain in large quantity for the court and the emperor to give as gifts.

Orientalism in early modern France refers to the interaction of pre-modern France with the Orient, and especially the cultural, scientific, artistic and intellectual impact of these interactions, ranging from the academic field of Oriental studies to Orientalism in fashions in the decorative arts.

The Nevers manufactory was a French manufacturing centre for faience in the city of Nevers. The first factory was started around 1588 by three Italian brothers, who brought the majolica tradition with them. A porcelain manufactury in Nevers was also mentioned in 1844 by Alexandre Brongniart, but little is known about it.

French porcelain has a history spanning a period from the 17th century to the present. The French were heavily involved in the early European efforts to discover the secrets of making the hard-paste porcelain known from Chinese and Japanese export porcelain. They succeeded in developing soft-paste porcelain, but Meissen porcelain was the first to make true hard-paste, around 1710, and the French took over 50 years to catch up with Meissen and the other German factories.

Chinese Tartary is an archaic geographical term used especially during the time of the Qing Dynasty. The term was used as early as 1734 on a map created by the French geographer and cartographer Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697–1782) who published the map in the Nouvel atlas de la Chine, de la Tartarie Chinoise et du Thibet in 1738. D’Anville’s map was based on work ordered by the Emperor of China and conducted by Chinese under the supervision of the Jesuits. Also published in 1738 was A description of the empire of China and Chinese-Tartary together with the kingdoms of Korea, and Tibet by Father Jean-Baptiste Du Halde. He went on to write in 1741 The General History of China Containing a Geographical, Historical, Chronological, Political and Physical Description of the Empire of China, Chinese-Tartary, Corea and Thibet. Modern areas today that were described by their work as falling within Chinese Tartary included: