Hyecho was a Korean Buddhist monk from Silla, one of Korea's Three Kingdoms. He is primarily remembered for his account of his travels in medieval India, the Wang Ocheonchukguk Jeon.

Hinduism in Afghanistan is practiced by a tiny minority of Afghans, about 30-40 individuals as of 2021, who live mostly in the cities of Kabul and Jalalabad. Afghan Hindus are ethnically Pashtun, Hindkowan (Hindki), Punjabi, or Sindhi and primarily speak Dari, Pashto, Hindko, Punjabi, Sindhi, and Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu).

Wang ocheonchukguk jeon is a travelogue by Buddhist monk Hyecho from the Kingdom of Silla, who traveled from Korea to India, in the years 723 - 727/728 CE.

Zunbil, also written as Zhunbil, or Rutbils of Zabulistan, was a royal dynasty south of the Hindu Kush in present southern Afghanistan region. They were a dynasty of Hephthalite origin. They ruled from circa 680 AD until the Saffarid conquest in 870 AD. The Zunbil dynasty was founded by Rutbil, the elder brother of the Turk Shahi ruler, who ruled over the Hephthalite kingdom from his capital in Kabul. The Zunbils are described as having Turkish troops in their service by Arabic sources like Tarikh al-Tabari and Tarikh-i Sistan. However the term "Turk" was used in an inaccurate and loose way.

The Hindu Shahis, also referred to as the Kabul Shahis and Uḍi Śāhis, were a Rajputa dynasty established between 843 CE and 1026 CE. They endured multiple waves of conquests for nearly two centuries and their core territory was described as having contained the regions of Eastern Afghanistan and Gandhara, encompassing the area up to the Sutlej river in modern day Punjab, expanding into the Kangra Valley. The empire was founded by Kallar in c. 843 CE after overthrowing Lagaturman, the last Turk Shahi king.

The Nezak Huns, also Nezak Shahs, was a significant principality in the south of the Hindu Kush region of South Asia from circa 484 to 665 CE. Despite being traditionally identified as the last of the four Hunnic states in South Asia, their ethnicity remains disputed and speculative. The dynasty is primarily evidenced by coinage inscribing a characteristic water-buffalo-head crown and an eponymous legend.

The Turk Shahis or Kabul Shahis were a dynasty of Western Turk, or mixed Turko-Hephthalite, or a group of Hephthalites origin, that ruled from Kabul and Kapisa to Gandhara in the 7th to 9th centuries AD. They may have been of Khalaj ethnicity. The Gandhara territory may have been bordering the Kashmir kingdom and the Kannauj kingdom to the east. From the 560s, the Western Turks had gradually expanded southeasterward from Transoxonia, and occupied Bactria and the Hindu Kush region, forming largely independent polities. The Turk Shahis may have been a political extension of the neighbouring Western Turk Yabghus of Tokharistan. In the Hindu Kush region, they replaced the Nezak Huns – the last dynasty of Bactrian rulers with origins among the Xwn (Xionite) and/or Huna peoples.

The Lawīk dynasty was the last native dynasty which ruled Ghazni prior to the Ghaznavid conquest in the present-day Afghanistan. Lawiks were originally Hindus, but later became Muslims. They were closely related to the Hindu Shahis, and after 877, ruled under the Hindu Shahi suzerainty.

The Tokhara Yabghus or Yabghus of Tokharistan were a dynasty of Western Turk–Hephthalite sub-kings with the title "Yabghus", who ruled from 625 CE in the area of Tokharistan north and south of the Oxus River, with some smaller remnants surviving in the area of Badakhshan until 758 CE. Their legacy extended to the southeast where it came into contact with the Turk Shahis and the Zunbils until the 9th century CE.

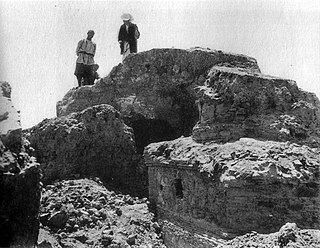

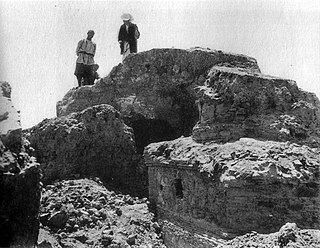

The Fondukistan monastery was a Buddhist monastery located at the very top of a conical hill next to the Ghorband Valley, Parwan Province, about 50 kilometers northwest of Kabul. The monastery dates to the early 8th century CE, with a terminus post quem in 689 CE obtained through numismatic evidence, so that the Buddhist art of the site has been estimated to around 700 CE. This is the only secure date for this artistic period in the Hindu Kush, and it serves as an important chronological reference point.

Khair Khaneh is an archaeological site located near Kabul, Afghanistan that was excavated in the 1930s by Joseph Hackin.

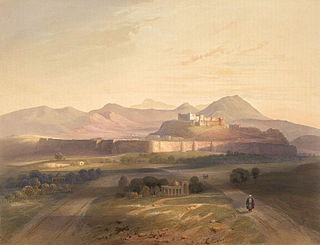

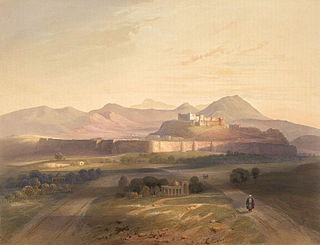

Tepe Sardar, also Tapa Sardar or Tepe-e-Sardar, is an ancient Buddhist monastery in Afghanistan. It is located near Ghazni, and it dominates the Dasht-i Manara plain. The site displays two major artistic phases, an Hellenistic phase during the 3rd to 6th century CE, followed by a Sinicized-Indian phase during the 7th to 9th century.

Alkhis was a ruler of the area of Zabul, with its capital at Gazan (Ghazni) in Afghanistan in the early decades of the 8th century CE. He was the son of Khuras. He expanded his territory as far north of the region of Band-e Amir, west of Bamiyan. Although not listed in contemporary Chinese sources, Alkhis may have been a member of the Zunbil ruler of Zabulistan, and was probably of the same ethnicity as the nearby Turk Shahis ruling in Kabul at that time.

The Seal of Khingila is an historical seal from the region of Bactria, on southern Central Asia. The seal was published recently by Pierfrancesco Callieri and Nicholas Sims-Williams. It is now in the private collection of Mr. A. Saeedi (London). Kurbanov considers it as a significant Hephthalite seal. It has also been considered as intermediate between the Kidarites and the Hephthalites.

Tepe Maranjan, previously known as Siyah Sang, is a small hill in southeastern Kabul, Afghanistan.

Barha Tegin was the first ruler of the Turk Shahis. He is only known in name from the accounts of the Muslim historian Al-Biruni and reconstructions from Chinese sources, and the identification of his coinage remains conjectural.

Khingala, also transliterated Khinkhil, Khinjil or Khinjal, was a ruler of the Turk Shahis. He is only known in name from the accounts of the Muslim historian Ya'qubi and from an epigraphical source, the Gardez Ganesha. The identification of his coinage remains conjectural.

Bo Fuzhun, also Bofuzhun was a ruler of the Turk Shahis. He is only known in name from Chinese imperial accounts and possibly numismatic sources. The identification of his coinage remains conjectural.

Shōshin Kuwayama is a Japanese historian and archaeologist. He has been Professor Emeritus at the Institute for Research in the Humanities at Kyoto University, and is credited with contributing to the "formation of an entire generation of scholars in Japan and abroad". Kuwayama is one of the leading scholars in the area of historical interactions between China and India, and especially researches the southern Hindukush region. He led extensive archaeological projects in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Hindu Shahi–Saffarid wars were a series of military conflicts fought between the forces of the Hindu Shahis and the Saffarids.