Tularemia, also known as rabbit fever, is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. Symptoms may include fever, skin ulcers, and enlarged lymph nodes. Occasionally, a form that results in pneumonia or a throat infection may occur.

A lymphocyte is one of the subtypes of a white blood cell in a vertebrate's immune system. Lymphocytes include natural killer cells, T cells, and B cells. They are the main type of cell found in lymph, which prompted the name "lymphocyte".

Chlamydia trachomatis, commonly known as chlamydia, is a bacterium that can replicate only in human cells. It causes chlamydia, which can manifest in various ways, including: trachoma, lymphogranuloma venereum, nongonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, salpingitis, pelvic inflammatory disease. C. trachomatis is the most common infectious cause of blindness and the most common sexually transmitted bacterium.

Listeria is a genus of bacteria that, until 1992, contained 10 known species, each containing two subspecies. As of 2019, 20 species were identified. Named after the British pioneer of sterile surgery Joseph Lister, the genus received its current name in 1940. Listeria species are Gram-positive, rod-shaped, and facultatively anaerobic, and do not produce endospores. The major human pathogen in the genus Listeria is L. monocytogenes. It is usually the causative agent of the relatively rare bacterial disease listeriosis, an infection caused by eating food contaminated with the bacteria. Listeriosis can cause serious illness in pregnant women, newborns, adults with weakened immune systems and the elderly, and may cause gastroenteritis in others who have been severely infected.

Legionella pneumophila is a thin, aerobic, pleomorphic, flagellated, non-spore-forming, Gram-negative bacterium of the genus Legionella. L. pneumophila is the primary human pathogenic bacterium in this group and is the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease, also known as legionellosis.

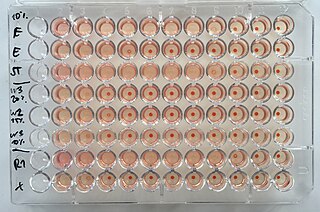

The hemagglutination assay and the hemagglutination inhibition assay were developed in 1941–42 by American virologist George Hirst as methods for quantifying the relative concentration of viruses, bacteria, or antibodies.

Coccidia (Coccidiasina) are a subclass of microscopic, spore-forming, single-celled obligate intracellular parasites belonging to the apicomplexan class Conoidasida. As obligate intracellular parasites, they must live and reproduce within an animal cell. Coccidian parasites infect the intestinal tracts of animals, and are the largest group of apicomplexan protozoa.

Virulence factors are molecules produced by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa that add to their effectiveness and enable them to achieve the following:

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is a Gram-negative bacterium that is unusual in its tropism to neutrophils. It causes anaplasmosis in sheep and cattle, also known as tick-borne fever and pasture fever, and also causes the zoonotic disease human granulocytic anaplasmosis.

Medical microbiology , the large subset of microbiology that is applied to medicine, is a branch of medical science concerned with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. In addition, this field of science studies various clinical applications of microbes for the improvement of health. There are four kinds of microorganisms that cause infectious disease: bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses, and one type of infectious protein called prion.

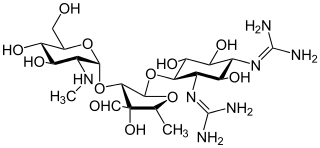

G418 (Geneticin) is an aminoglycoside antibiotic similar in structure to gentamicin B1. It is produced by Micromonospora rhodorangea. G418 blocks polypeptide synthesis by inhibiting the elongation step in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Resistance to G418 is conferred by the neo gene from Tn5 encoding an aminoglycoside 3'-phosphotransferase, APT 3' II. G418 is an analog of neomycin sulfate, and has similar mechanism as neomycin. G418 is commonly used in laboratory research to select genetically engineered cells. In general for bacteria and algae concentrations of 5 μg/mL or less are used, for mammalian cells concentrations of approximately 400 μg/mL are used for selection and 200 μg/mL for maintenance. However, optimal concentration for resistant clones selection in mammalian cells depends on the cell line used as well as on the plasmid carrying the resistance gene, therefore antibiotic titration should be done to find the best condition for every experimental system. Titration should be done using antibiotic concentrations ranging from 100 μg/mL up to 1400 μg/mL. Resistant clones selection could require from 1 to up to 3 weeks.

Bartonella bacilliformis is a proteobacterium, Gram negative aerobic, pleomorphic, flagellated, motile, coccobacillary, 2–3 μm long, 0.2–0.5 μm wide, and a facultative intracellular bacterium.

A pneumococcal infection is an infection caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, which is also called the pneumococcus. S. pneumoniae is a common member of the bacterial flora colonizing the nose and throat of 5–10% of healthy adults and 20–40% of healthy children. However, it is also a cause of significant disease, being a leading cause of pneumonia, bacterial meningitis, and sepsis. The World Health Organization estimate that in 2005 pneumococcal infections were responsible for the death of 1.6 million children worldwide.

Multidrug tolerance or antibiotic tolerance is the ability of a disease-causing microorganism to resist being killed by antibiotics or other antimicrobials. It is mechanistically distinct from multidrug resistance: It is not caused by mutant microbes, but rather by microbial cells that exist in a transient, dormant, non-dividing state. Microorganisms that display multidrug tolerance can be bacteria, fungi or parasites.

Virus quantification involves counting the number of viruses in a specific volume to determine the virus concentration. It is utilized in both research and development (R&D) in commercial and academic laboratories as well as production situations where the quantity of virus at various steps is an important variable. For example, the production of viral vaccines, recombinant proteins using viral vectors and viral antigens all require virus quantification to continually adapt and monitor the process in order to optimize production yields and respond to ever changing demands and applications. Examples of specific instances where known viruses need to be quantified include clone screening, multiplicity of infection (MOI) optimization and adaptation of methods to cell culture. This page discusses various techniques currently used to quantify viruses in liquid samples. These methods are separated into two categories, traditional vs. modern methods. Traditional methods are industry-standard methods that have been used for decades but are generally slow and labor-intensive. Modern methods are relatively new commercially available products and kits that greatly reduce quantification time. This is not meant to be an exhaustive review of all potential methods, but rather a representative cross-section of traditional methods and new, commercially available methods. While other published methods may exist for virus quantification, non-commercial methods are not discussed here.

The antibodies from lymphocyte secretions (ALS) assay is an immunological assay to detect active diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid etc. Recently, ALS assay nods the scientific community as it is rapidly used for diagnosis of Tuberculosis. The principle is based on the secretion of antibody from in vivo activated plasma B cells found in blood circulation for a short period of time in response to TB-antigens during active TB infection rather than latent TB infection.