The People Power Revolution, also known as the EDSA Revolution or the February Revolution, was a series of popular demonstrations in the Philippines, mostly in Metro Manila, from February 22 to 25, 1986. There was a sustained campaign of civil resistance against regime violence and electoral fraud. The nonviolent revolution led to the departure of Ferdinand Marcos, the end of his 20-year dictatorship and the restoration of democracy in the Philippines.

Fabian Crisologo Ver was a Filipino military officer who served as the Commanding Officer of the Armed Forces of the Philippines under President Ferdinand Marcos.

Camp General Rafael T. Crame is the national headquarters of the Philippine National Police (PNP) located along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in Quezon City. It is situated across EDSA from Camp Aguinaldo, the national headquarters of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). Prior to the establishment of the civilian PNP, Camp Crame was the national headquarters of the Philippine Constabulary, a gendarmerie-type military police force which was the PNP's predecessor.

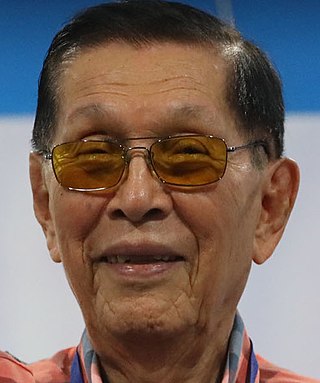

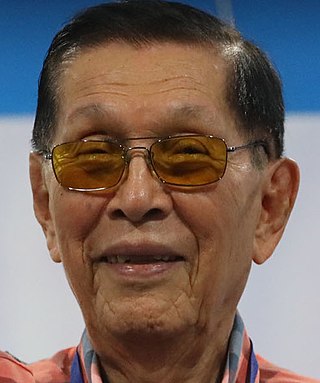

Juan Valentin Furagganan Ponce Enrile Sr.,, also referred to by his initials JPE, is a Filipino politician and lawyer who served as 21st President of the Senate of the Philippines from 2008 to 2013 and known for his role in the administration of Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos; his role in the failed coup that helped hasten the 1986 People Power Revolution and the ouster of Marcos; and his tenure in the Philippine legislature in the years after the revolution. Enrile has served four terms in the Senate, in a total of twenty-two years, he holds the third longest-tenure in the history of the upper chamber. In 2022, at the age of 98, he returned to government office as the Chief Presidential Legal Counsel in the administration of President Bongbong Marcos.

Gregorio "Gringo" Ballesteros Honasan II, is a Filipino politician and a cashiered Philippine Army officer who led unsuccessful coups d'état against President Corazon Aquino. He played a key role in the 1986 EDSA Revolution that toppled President Ferdinand Marcos, and participated in the EDSA III rallies in 2001 that preceded the May 1 riots near Malacañang Palace.

The history of the Philippines, from 1965 to 1986, covers the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. The Marcos era includes the final years of the Third Republic (1965–1972), the Philippines under martial law (1972–1981), and the majority of the Fourth Republic (1981–1986). By the end of the Marcos dictatorial era, the country was experiencing a debt crisis, extreme poverty, and severe underemployment.

The Four Day Revolution is a 1988 Australian television film directed by Robert Markowitz and written by David Williamson. The story is about the journey and the love affair of an American foreign correspondent set during the final years of Ferdinand Marcos' dictatorship in the Philippines, from the assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr. in 1983 to the People Power Revolution in 1986, as well as other key events that led to the ouster of Marcos.

From 1986 to 1987, there were several plots to overthrow Philippine President Corazon Aquino involving various members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines. A significant number of the military participants in these attempts belonged to the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), while others were identified loyalists of former President Ferdinand Marcos, who had been deposed in the People Power Revolution in late February 1986.

Corazon Aquino became the 11th President of the Philippines following the People Power Revolution or EDSA 1, and spanned a six-year period from February 25, 1986, to June 30, 1992. Aquino's relatively peaceful ascension to the Philippine presidency signaled the end of authoritarian rule of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, and drew her and the Filipino people international acclaim and admiration.

The Reform the Armed Forces Movement, also referred to by the acronym RAM, was a cabal of officers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) known for several attempts to seize power in the Philippines during the 1980s and 1990s. In 1986, some of these officers launched a failed coup d'état against Ferdinand Marcos, prompting a large number of civilians to attempt to prevent Marcos from wiping the RAM rebels out. This eventually snowballed into the 1986 People Power revolution which ended the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and forced him into exile. RAM later attempted six coups d'état against the administration of Corazon Aquino.

Victor Batac was the former director of the Directorate for Logistics of the Philippine National Police.

1986 in the Philippines details events of note that happened in the Philippines in the year 1986.

The People Power Revolution was a series of popular demonstrations in the Philippines that began in 1983 and culminated in 1986. The methods used amounted to a sustained campaign of civil resistance against regime violence and electoral fraud. This case of nonviolent revolution led to the toppling of dictator Ferdinand Marcos and the restoration of the country's democracy.

The Siege at Hotel Delfino in Tuguegarao, Cagayan in the Philippines, took place on March 4, 1990. A private army estimated at 300 men seized the hotel under the command of suspended Cagayan governor Rodolfo "Agi" Aguinaldo, a fierce critic of the administration of President Corazon Aquino and the Communist insurgency in the Philippines. The incident was an offshoot of the 1989 Philippine coup d'état attempt that Aguinaldo publicly supported, which prompted his suspension and arrest. The standoff ended violently after several hours, leaving 14 people dead, including a general who tried to arrest him.

Victor Navarro Corpus was a Filipino military officer and public official best known for his 1970 defection from the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to the New People's Army of the Communist Party of the Philippines during the authoritarian regime of Ferdinand Marcos, for his defection from the NPA in 1976, his return to the AFP after the 1986 People Power Revolution, and his later role as chief of the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (ISAFP).

The military history of the Philippines during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, especially the 14-year period between Marcos' proclamation of Martial Law in September 1972 and his eventual ouster through the People Power Revolution of 1986, was characterized by rapid changes linked to Marcos' use of the military as his "martial law implementor".

The February 1986 Reform the Armed Forces Movement coup was set in motion by the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) under the leadership of Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile to depose then-president Ferdinand Marcos, but was discovered and aborted in its earliest stages on February 22, 1986. The coup's intent was to take advantage of the public disruption arising from revelations of cheating during the 1986 Philippine presidential election, and replace Marcos with a military junta which would include Enrile, Philippine Constabulary Chief Fidel V. Ramos, then-Presidential Candidate Corazon Aquino, and Roman Catholic Cardinal Jaime Sin, among others, which Enrile and the RAM Colonels would control from behind the scenes.

On August 28, 1987, a coup d'état against the government of Philippine President Corazon Aquino was staged by members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) belonging to the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) led by Colonel Gregorio Honasan, who had been a former top aide of ousted Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile, one of the instigators of the People Power Revolution that brought Aquino to power in 1986. The coup was repelled by military forces loyal to Aquino within the day, although Honasan managed to escape.

On January 27, 1987, a coup d'état against the government of Philippine President Corazon Aquino was staged by civilian and military supporters of Aquino's deposed predecessor, Ferdinand Marcos. The soldiers were members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) who belonged to the Guardians Brotherhood, Inc (GBI) led by Colonel Oscar Canlas. They launched failed attacks on Philippine Air Force (PAF) installations at Villamor Air Base in Pasay and Sangley Point Air Station in Cavite, and occupied the GMA-7 television station in Quezon City for 61 hours before surrendering on January 29.

The siege of the Manila Hotel was an occupation of the Manila Hotel, a luxury hotel in the Philippine capital Manila, led by former vice-presidential candidate Arturo Tolentino and other military and civilian supporters of deposed President Ferdinand Marcos as part of a coup attempt to overthrow his successor, Corazon Aquino and restore him to power, on 6–8 July 1986. The coup failed to gain extensive support, and ended on 8 July with the departure of most participants and the surrender of others.