In geology, felsic is a modifier describing igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz. It is contrasted with mafic rocks, which are relatively richer in magnesium and iron. Felsic refers to silicate minerals, magma, and rocks which are enriched in the lighter elements such as silicon, oxygen, aluminium, sodium, and potassium. Felsic magma or lava is higher in viscosity than mafic magma/lava, and have low temperatures to keep the felsic minerals molten.

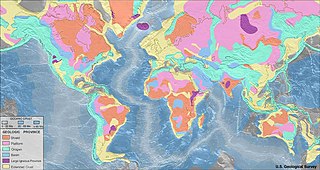

Granite is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies underground. It is common in the continental crust of Earth, where it is found in igneous intrusions. These range in size from dikes only a few centimeters across to batholiths exposed over hundreds of square kilometers.

Gabbro is a phaneritic, mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is chemically equivalent to rapid-cooling, fine-grained basalt. Much of the Earth's oceanic crust is made of gabbro, formed at mid-ocean ridges. Gabbro is also found as plutons associated with continental volcanism. Due to its variant nature, the term gabbro may be applied loosely to a wide range of intrusive rocks, many of which are merely "gabbroic". By rough analogy, gabbro is to basalt as granite is to rhyolite.

A mafic mineral or rock is a silicate mineral or igneous rock rich in magnesium and iron. Most mafic minerals are dark in color, and common rock-forming mafic minerals include olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. Common mafic rocks include basalt, diabase and gabbro. Mafic rocks often also contain calcium-rich varieties of plagioclase feldspar. Mafic materials can also be described as ferromagnesian.

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized silicate grains, cemented together by another mineral. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

The rubidium–strontium dating method (Rb–Sr) is a radiometric dating technique, used by scientists to determine the age of rocks and minerals from their content of specific isotopes of rubidium (87Rb) and strontium. One of the two naturally occurring isotopes of rubidium, 87Rb, decays to 87Sr with a half-life of 49.23 billion years. The radiogenic daughter, 87Sr, produced in this decay process is the only one of the four naturally occurring strontium isotopes that was not produced exclusively by stellar nucleosynthesis predating the formation of the Solar System. Over time, decay of 87Rb increases the amount of radiogenic 87Sr while the amount of other Sr isotopes remains unchanged.

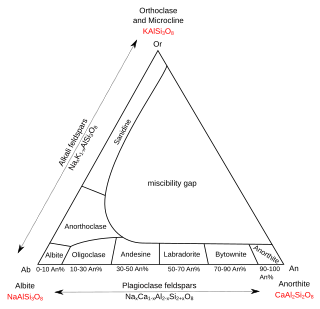

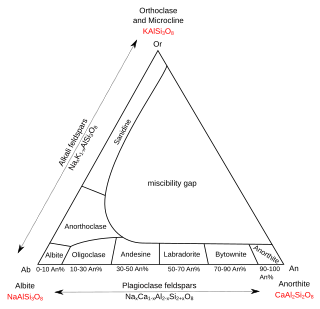

Feldspar is a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the plagioclase (sodium-calcium) feldspars and the alkali (potassium-sodium) feldspars. Feldspars make up about 60% of the Earth's crust and 41% of the Earth's continental crust by weight.

Plagioclase ( PLAJ-(ee)-ə-klayss, PLAYJ-, -klayz) is a series of tectosilicate (framework silicate) minerals within the feldspar group. Rather than referring to a particular mineral with a specific chemical composition, plagioclase is a continuous solid solution series, more properly known as the plagioclase feldspar series. This was first shown by the German mineralogist Johann Friedrich Christian Hessel (1796–1872) in 1826. The series ranges from albite to anorthite endmembers (with respective compositions NaAlSi3O8 to CaAl2Si2O8), where sodium and calcium atoms can substitute for each other in the mineral's crystal lattice structure. Plagioclase in hand samples is often identified by its polysynthetic crystal twinning or "record-groove" effect.

Anorthite (an = not, ortho = straight) is the calcium endmember of the plagioclase feldspar mineral series. The chemical formula of pure anorthite is CaAl2Si2O8. Anorthite is found in mafic igneous rocks. Anorthite is rare on the Earth but abundant on the Moon.

Andesite is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predominantly of sodium-rich plagioclase plus pyroxene or hornblende.

Anorthosite is a phaneritic, intrusive igneous rock characterized by its composition: mostly plagioclase feldspar (90–100%), with a minimal mafic component (0–10%). Pyroxene, ilmenite, magnetite, and olivine are the mafic minerals most commonly present.

Within the field of geology, Bowen's reaction series is the work of the Canadian petrologist Norman L. Bowen, who summarized, based on experiments and observations of natural rocks, the sequence of crystallization of common silicate minerals from typical basaltic magma undergoing fractional crystallization. Bowen's reaction series is able to explain why certain types of minerals tend to be found together while others are almost never associated with one another. He experimented in the early 1900s with powdered rock material that was heated until it melted and then allowed to cool to a target temperature whereupon he observed the types of minerals that formed in the rocks produced. He repeated this process with progressively cooler temperatures and the results he obtained led him to formulate his reaction series which is still accepted today as the idealized progression of minerals produced by cooling basaltic magma that undergoes fractional crystallization. Based upon Bowen's work, one can infer from the minerals present in a rock the relative conditions under which the material had formed.

Restite is the residual material left at the site of melting during the in place production of magma.

Cumulate rocks are igneous rocks formed by the accumulation of crystals from a magma either by settling or floating. Cumulate rocks are named according to their texture; cumulate texture is diagnostic of the conditions of formation of this group of igneous rocks. Cumulates can be deposited on top of other older cumulates of different composition and colour, typically giving the cumulate rock a layered or banded appearance.

In geology, igneous differentiation, or magmatic differentiation, is an umbrella term for the various processes by which magmas undergo bulk chemical change during the partial melting process, cooling, emplacement, or eruption. The sequence of magmas produced by igneous differentiation is known as a magma series.

Fractional crystallization, or crystal fractionation, is one of the most important geochemical and physical processes operating within crust and mantle of a rocky planetary body, such as the Earth. It is important in the formation of igneous rocks because it is one of the main processes of magmatic differentiation. Fractional crystallization is also important in the formation of sedimentary evaporite rocks or simply fractional crystallization is the removal of early formed crystals from an Original homogeneous magma so that the crystals are prevented from further reaction with the residual melt.

Magmatic water, also known as juvenile water, is an aqueous phase in equilibrium with minerals that have been dissolved by magma deep within the Earth's crust and is released to the atmosphere during a volcanic eruption. It plays a key role in assessing the crystallization of igneous rocks, particularly silicates, as well as the rheology and evolution of magma chambers. Magma is composed of minerals, crystals and volatiles in varying relative natural abundance. Magmatic differentiation varies significantly based on various factors, most notably the presence of water. An abundance of volatiles within magma chambers decreases viscosity and leads to the formation of minerals bearing halogens, including chloride and hydroxide groups. In addition, the relative abundance of volatiles varies within basaltic, andesitic, and rhyolitic magma chambers, leading to some volcanoes being exceedingly more explosive than others. Magmatic water is practically insoluble in silicate melts but has demonstrated the highest solubility within rhyolitic melts. An abundance of magmatic water has been shown to lead to high-grade deformation, altering the amount of δ18O and δ2H within host rocks.

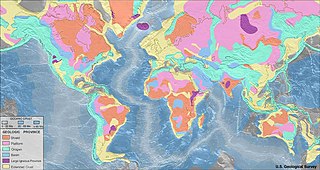

Igneous rock, or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

S-type granites are a category of granites first proposed in 1974. They are recognized by a specific set of mineralogical, geochemical, textural, and isotopic characteristics. S-type granites are over-saturated in aluminium, with an ASI index greater than 1.1 where ASI = Al2O3 / (CaO + Na2O +K2O) in mol percent; petrographic features are representative of the chemical composition of the initial magma as originally put forth by Chappell and White are summarized in their table 1.

I-type granites are a category of granites originating from igneous sources, first proposed by Chappell and White (1974). They are recognized by a specific set of mineralogical, geochemical, textural, and isotopic characteristics that indicate, for example, magma hybridization in the deep crust. I-type granites are saturated in silica but undersaturated in aluminum; petrographic features are representative of the chemical composition of the initial magma. In contrast S-type granites are derived from partial melting of supracrustal or "sedimentary" source rocks.