Related Research Articles

Public finance refers to the monetary resources available to governments and also to the study of finance within government and role of the government in the economy. As a subject of study, it is the branch of economics which assesses the government revenue and government expenditure of the public authorities and the adjustment of one or the other to achieve desirable effects and avoid undesirable ones. The purview of public finance is considered to be threefold, consisting of governmental effects on:

- The efficient allocation of available resources;

- The distribution of income among citizens; and

- The stability of the economy.

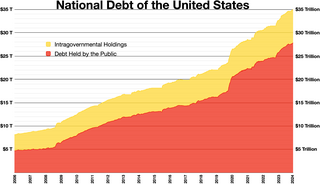

The national debt of the United States is the total national debt owed by the federal government of the United States to Treasury security holders. The national debt at any point in time is the face value of the then-outstanding Treasury securities that have been issued by the Treasury and other federal agencies. The terms "national deficit" and "national surplus" usually refer to the federal government budget balance from year to year, not the cumulative amount of debt. In a deficit year the national debt increases as the government needs to borrow funds to finance the deficit, while in a surplus year the debt decreases as more money is received than spent, enabling the government to reduce the debt by buying back some Treasury securities. In general, government debt increases as a result of government spending and decreases from tax or other receipts, both of which fluctuate during the course of a fiscal year. There are two components of gross national debt:

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) is an agreement, among all the 27 member states of the European Union (EU), to facilitate and maintain the stability of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Based primarily on Articles 121 and 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, it consists of fiscal monitoring of member states by the European Commission and the Council of the European Union, and the issuing of a yearly Country-Specific Recommendation for fiscal policy actions to ensure a full compliance with the SGP also in the medium-term. If a member state breaches the SGP's outlined maximum limit for government deficit and debt, the surveillance and request for corrective action will intensify through the declaration of an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP); and if these corrective actions continue to remain absent after multiple warnings, a member state of the eurozone can ultimately also be issued economic sanctions. The pact was outlined by a European Council resolution in June 1997, and two Council regulations in July 1997. The first regulation "on the strengthening of the surveillance of budgetary positions and the surveillance and coordination of economic policies", known as the "preventive arm", entered into force 1 July 1998. The second regulation "on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure", sometimes referred to as the "dissuasive arm" but commonly known as the "corrective arm", entered into force 1 January 1999.

The 2004 Greek financial audit was a 2004 investigation into the true extent of Greece's public finances. It examined government revenue, spending and the level of Greek government borrowing.

The Barnett formula is a mechanism used by the Treasury in the United Kingdom to automatically adjust the amounts of public expenditure allocated to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales to reflect changes in spending levels allocated to public services in England, Scotland and Wales, as appropriate. The formula applies to a large proportion, but not the whole, of the devolved governments' budgets − in 2013–14 it applied to about 85% of the Scottish Parliament's total budget.

The economy of Wales is part of the wider economy of the United Kingdom, and encompasses the production and consumption of goods, services and the supply of money in Wales.

The economy of Scotland is an open mixed economy, mainly services based, which is the second largest economy amongst the countries of the United Kingdom. It had an estimated nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of £218.0 billion in 2023, including oil and gas extraction in the country's continental shelf region. Since the Acts of Union 1707, Scotland's economy has been closely aligned with the economy of the rest of the United Kingdom (UK), and England has historically been its main trading partner. Scotland conducts the majority of its trade within the UK: in 2017, Scotland's exports totalled £81.4 billion, of which £48.9 billion (60%) was within the UK, £14.9 billion with the European Union (EU), and £17.6 billion with other parts of the world. Scotland's imports meanwhile totalled £94.4 billion including intra-UK trade leaving Scotland with a trade deficit of £10.4 billion in 2017.

The United States budget comprises the spending and revenues of the U.S. federal government. The budget is the financial representation of the priorities of the government, reflecting historical debates and competing economic philosophies. The government primarily spends on healthcare, retirement, and defense programs. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office provides extensive analysis of the budget and its economic effects. CBO estimated in February 2024 that Federal debt held by the public is projected to rise from 99 percent of GDP in 2024 to 116 percent in 2034 and would continue to grow if current laws generally remained unchanged. Over that period, the growth of interest costs and mandatory spending outpaces the growth of revenues and the economy, driving up debt. Those factors persist beyond 2034, pushing federal debt higher still, to 172 percent of GDP in 2054.

Full fiscal autonomy (FFA) – also known as devolution max, devo-max, or fiscal federalism – is a particular form of far-reaching devolution proposed for Scotland and for Wales. The term has come to describe a constitutional arrangement in which instead of receiving a block grant from His Majesty's Treasury as at present, the Scottish Parliament or the Senedd would receive all taxation levied in Scotland or Wales; it would be responsible for most spending in Scotland or Wales but make payments to the UK government to cover Scotland or Wales's share of the cost of providing certain UK-wide services, largely defence and foreign relations. Scottish/Welsh fiscal autonomy – stopping short of full political independence – is usually promoted by advocates of a federal United Kingdom.

Canadian public debt, or general government debt, is the liabilities of the government sector. Government gross debt consists of liabilities that are a financial claim that requires payment of interest and/or principal in future. They consist mainly of Treasury bonds, but also include public service employee pension liabilities. Changes in debt arise primarily from new borrowing, due to government expenditures exceeding revenues.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is a non-departmental public body funded by the UK Treasury that provides independent economic forecasts and independent analysis of the public finances.

The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003 (FRBMA) is an Act of the Parliament of India to institutionalize financial discipline, reduce India's fiscal deficit, improve macroeconomic management and the overall management of the public funds by moving towards a balanced budget and strengthen fiscal prudence. The main purpose was to eliminate revenue deficit of the country and bring down the fiscal deficit to a manageable 3% of the GDP by March 2008. However, due to the 2007 international financial crisis, the deadlines for the implementation of the targets in the act was initially postponed and subsequently suspended in 2009. In 2011, given the process of ongoing recovery, Economic Advisory Council publicly advised the Government of India to reconsider reinstating the provisions of the FRBMA. N. K. Singh is currently the Chairman of the review committee for Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003, under the Ministry of Finance (India), Government of India.

Government spending in the United Kingdom, also referred to as public spending, is the total spent by Central Government departments and certain other bodies as authorised by Parliament through the Estimates process. It includes net spending by the three devolved governments: the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Executive.

The United Kingdom national debt is the total quantity of money borrowed by the Government of the United Kingdom at any time through the issue of securities by the British Treasury and other government agencies.

Audits of Greece's public finances during the period 2009–2010 were undertaken by the EU authorities. Since joining the Euro zone, Greece's public finances markedly deviated from the debt and deficit limits set by Stability and Growth Pact.

The federal budget of Russia is the leading element of the budget system of Russia. It is a major state financial plan for the fiscal year, which has the force of law after its approval by the Russian parliament and signed into law by the President of Russia.

The Fourteenth Finance Commission of India was a finance commission constituted on 2 January 2013. The commission's chairman was former Reserve Bank of India governor Y. V. Reddy and its members were Sushma Nath, M. Govinda Rao, Abhijit Sen, Sudipto Mundle, and AN Jha. The recommendations of the commission entered force in April 2015; they take effect for a five-year period from that date.

Taxation in Wales typically comprises payments to one or more of the three different levels of government: the UK government, the Welsh Government, and local government.

From 1999 to 2022 Wales has had a negative fiscal balance, due to public spending in Wales exceeding tax revenue. For the 2018–19 fiscal year, the fiscal deficit was about 19.4 percent of Wales's estimated GDP, compared to 2 percent for the United Kingdom as a whole. All UK nations and regions except for East, South East England and London have a deficit. Wales' fiscal deficit per capita of £4,300 is the second highest of the economic regions, after the Northern Ireland fiscal deficit, which is nearly £5,000 per capita.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "About Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland". www.gov.scot.

- 1 2 "The State of the State 2016-17 | Devolved governments of the UK Deloitte" (PDF).

- ↑ Swinney, John (2022-08-24). "GERS figures: Why Scotland's deficit is falling faster than UK Government".

- ↑ "Government Expenditure and Revenue in Scotland (GERS): 2018 to 2019".

- ↑ "Why are the Gers figures contested?". BBC News. 23 August 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "Controversial financial figures are failing to give true picture of taxes and expenditure in Scotland". National Newspaper. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "Finance committee" (PDF). Scottish Government. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "GERS publications". Scottish Government website. Scottish Government. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ Cuthbert, Jim; Cuthbert, Margaret; Ashcroft, Brian; Malloy, Eleanor; Tissier, Sarah Le (December 2, 1998). "A critique of GERS: government expenditure and revenue in Scotland". Quarterly Economic Commentary. 24 (1): 49–58 – via pureportal.strath.ac.uk.

- ↑ "GERS 1999" (PDF). Scottish Government. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "GERS methodology changes" (PDF). University of Glasgow.

- ↑ "A New GERS".

- ↑ "Playing politics with the 'dismal science'". BBC News. March 9, 2016.

- ↑ McLaren, John (25 August 2016). "GERS sinks White Paper's economic arguments for independence". The Herald. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish public spending deficit rises, say latest Gers figures". BBC News. March 12, 2014.

- ↑ Webb, Merryn Somerset (May 16, 2014). "Scotland's fiscal independence is inevitable". Archived from the original on 2017-03-15. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ↑ Merryn Somerset Webb [@MerrynSW] (March 16, 2017). "I took that blog down and corrected its while back! It was wrong you see..." (Tweet). Retrieved 11 September 2017– via Twitter.

- ↑ Graeme Roy (28 March 2017). "Estimating Scotland's fiscal position". Fraser of Allander Institute.

- ↑ Murphy, Richard. "Why economic data provided by London will not help the Scottish independence debate".

- ↑ Michael Glackin. "Proper statistics are elementary to economic policy, dear Watson". The Times. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ↑ Kevin Hague (7 September 2017). "Economic facts have become the SNP's enemy and latest deficit figures lay that bare". Daily Record. Retrieved 13 November 2018.