Founding and first 90 years

The cemetery was founded in 1884, and was the only cemetery in the area until Forest Lawn Memorial Park was constructed in 1906. [3] The site was heavily wooded, and its 4 percent grade provided good drainage. [4]

The burial ground was purchased by local builder Len C. Davis in 1919 and incorporated in late December [5] with capital stock worth $20,000 ($300,000 in 2024 dollars). (Each stock was worth $100 par value.) [6] A perpetual care trust [a] was also established for the first time. [8] Significant improvements were made [8] which included the addition of a 40-foot (12 m) high, electrically illuminated arch over the entrance on Glenwood Road. [9] Construction of a $14,000 ($246,802 in 2024 dollars), [10] 18-receiving vault chapel began in 1921. [11]

Mausoleum construction

The cemetery began planning for a large mausoleum in 1920, [12] although it was not begun until 1923. The mausoleum was 1,060 feet (320 m) long, [13] running along Sonora Avenue between W. Kenneth and Glenwood Roads. [9] [b] The $400,000 [14] ($7,339,029 in 2024 dollars), one-story [13] structure was made of reinforced concrete [15] and consisted of 12 distinct "buildings". [16] The interior of the mausoleum was clad in marble and had bronze finishings and cathedral glass windows. [13] [15] "Quaint" electric lamps provided interior illumination, [14] while skylights in the roof of each "building" provided additional light. [15] The mausoleum contained a total of 3,400 crypts. [13] Each crypt was 5 feet (1.5 m) high, [15] and there were five crypts in each room. [13] A dry-air circulation system in each crypt helped to encourage desiccation and reduce odor. [15] The cemetery assigned several sections of the mausoleum to local fraternal orders for burial of their dead. [13] The mausoleum also featured a number of "private rooms". Each private room contained two or more crypts, and had its own exterior window. [15] In the center of the mausoleum was a 60-foot (18 m) wide, 90-foot (27 m) deep [14] new chapel [13] [15] with white stucco exterior walls. [14] The chapel itself was clad in marble and mosaic tile [4] [14] and seated 200. It featured Italian vases 6 feet (1.8 m) high in which plants grew. [14] The chapel also contained 2,000 niches for the emplacement of cremation urns. [15]

The $60,000 ($1,107,305 in 2024 dollars) first phase of the construction consisted of a structure 35 feet (11 m) deep and 300 feet (91 m) long, containing 400 crypts. This portion of the mausoleum was constructed by local builder C.A. Cornell. [16]

In August 1924, the cemetery began construction on the north mausoleum, which expanded capacity to 5,700 crypts. [4] [14]

The original chapel, mausoleum, and cemetery office are all in the Spanish Colonial Revival style. [3] [c] [d]

A separate chapel in the Spanish Colonial style was constricted in the early 1920's, located in a central location on the cemetery grounds. In the late 1920's a crematory was added to the back end of the chapel, with two retorts. The first cremation was on May 23, 1932. The cremated remains were given to the family. At a later date two more retorts were added, making a total of four.

Hepburn ownership

By 1929, the 25-acre (10 ha) cemetery had 4,000 interments, [18] with about 10 percent of lots sold. [17] Len C. Davis and his wife divorced that same year. The cemetery was one of the disputed assets in the case. [19] In July 1930, a court ordered Len Davis to divest his interest in the cemetery in order to pay alimony to his wife. [20]

Davis sold the cemetery for $2 million ($41,400,000 in 2024 dollars) in March 1931 to a group of investors that included E. H. Dimity, Charles H. Johnston, and William H. Kittle. The new owners planned to build a large new mausoleum along Kenneth Road, and move the cemetery's main entrance there. [17] These plans were never acted on.

Local real estate developer David W. Hepburn was hired that same year to manage the cemetery, and purchased the burial ground some time between 1930 and 1946. [21] [e]

The cemetery completed a multi-year, $3 million ($39,600,000 in 2024 dollars) building project in 1949. [22] [23] The full extent of the project was not clear, but included a new wall around the property. The cemetery at that time planned to erect a 25,000-crypt mausoleum, [23] but this effort was never begun. In time Hepburn's son, David N. Hepburn, took over the cemetery's management. [24] David N. Hepburn was a highly respected cemetery operator both in the state and California and at one point was president of the Cemetery Association of America. [25] Grand View Memorial stopped scattering ashes in its various memorial gardens and terraces in the late 1970s after the buildup of remains became too noticeable. The cemetery started storing cremains for five years, and buried them if they were not claimed. [26] David N. Hepburn retired in 1990, after which Jack Grossman was employed as superintendent of the cemetery. [24]

Grand View Partners ownership

The Hepburns sold the cemetery to a new firm, Grand View Partners, in 1991. [21] Marsha Lee Howard, a veteran cemetery industry professional, was hired as the new superintendent. Howard employed her brother, Tom Trimble, as a groundskeeper from 1991 until 2003. [27] In 1998, people living near the cemetery complained about smoke and odors emanating from the burial ground's crematory. The cemetery was warned by the South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD; a state air pollution control agency) that its crematory was not in compliance with state and federal pollution control laws and regulations. [28] After a complaint by a plot owner, [f] a 1998 inspection of the cemetery by the Cemetery and Funeral Bureau (CFB) of the California Department of Consumer Affairs turned up numerous record-keeping problems, and the cemetery was fined $52,200 ($100,702 in 2024 dollars). [30]

Howard ownership

In 1999, Grand View partners sold the cemetery to Marsha Lee Howard and Moshe Goldsman. [24] [29] According to Howard's brother, Tom Trimble, the cemetery was already in disarray and disrepair when it was offered for sale. Howard purchased the property both as a means of advancing her career and because she wanted to restore the burial ground. [27] Howard lacked the money to buy Grand View outright, so she sought an investment partner. [27] Howard was the majority owner, with 51 percent. Moshe Goldsman was the sole minority owner, with the remaining 49 percent. [31]

According to Trimble, there were extensive cemetery practice, maintenance, and record-keeping problems at Grand View long before Howard purchased the burial ground. [31] The cemetery, he said, had no functioning lawn or tree care equipment, many headstones were leaning or had toppled over, and all irrigation was done by hand. Howard purchased a riding lawn mower, began regular mowing of the site, and started straightening headstones. She also had an irrigation sprinkler system installed in section M, the largest section at Grand View. [27]

The CFB inspected the cemetery again in 1999 after another complaint was filed, and once more fined Howard $52,200 ($98,529 in 2024 dollars) for failing to keep proper records. [30]

Howard suffered from Type 1 diabetes, and beginning in September 2002 suffered three life-threatening diabetes-related illnesses which left her hospitalized for long periods of time. According to Trimble, management of the cemetery declined significantly during these periods. [27]

Complaints about the crematory's smoke and odors continued. SCAQMD issued three notices that the cemetery had violated air pollution control standards, and one order of abatement by the end of 2003. Howard was required to make $37,000 ($63,244 in 2024 dollars) in crematory equipment upgrades and limit operations of the crematory to limit pollution. [28]

From early 2001 to mid 2005, the CFB received nine complaints from families complaining about cemetery operations. The CFB investigated, but could not verify the complaints. The agency did, however, issue a warning letter to Grand View Memorial in 2004 about its failure to maintain cemetery markers and plot boundary barriers in an acceptable condition. [30]

2005 scandal

In the spring of 2004, the state of California enacted legislation giving the CFB authority to inspect cemeteries and other burial sites on an annual basis (not just when a complaint was filed). [29] [32]

The first annual inspection of Grand View Memorial Park [29] [32] occurred in May 2005. [33] [g] The results of that inspection were made public in late October 2005. [34] [35] During the inspection, CFB inspectors discovered about 4,000 cremated remains [30] [32] [h] in cardboard boxes [29] and plastic containers [32] in storage rooms and on the floor of the mausoleum, [30] [29] in mausoleum crypts which should have held full-body remains, [37] in the chapel, and in a dumpster. [30] [29] [i] Most of the remains dated to the 1930s and 1940s, with smaller numbers from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. [29] [37] A few remains were from the 1990s. [37] Some containers had spilled, and the remains of several people were mixed together on the floor. [39] The remains of seven individuals were found in the chapel in temporary crypts, having never been permanently interred. [29] [33]

CFB inspectors found the cemetery's records in very poor condition. The records room was infested with rodents, [37] and records regarding some of the remains were so incomplete or were missing altogether that the remains could not be identified. [30] Maps of in-ground burials, mausoleum full-body crypt and cremains niche burials, and chapel burials were missing [40] or extremely inaccurate, sometimes showing remains where none were found and sometimes not depicting burials which others records indicated had occurred. [33] Later investigations revealed that a large number of cremated remains had been buried throughout the cemetery without records kept regarding their location. [36] Crematory records were in similar poor condition. [36]

The cemetery itself was in general disarray. Most areas were overgrown, and there were numerous dead trees and bushes. All buildings were in disrepair. [33] Groundskeeping tools, trash, [33] caskets and grave markers were scattered over the property [37] and throughout public buildings. [33] [j] So much trash and rodent feces had accumulated in the mausoleum that visitors could not access some crypts or niches. [33] In the below-ground portion of the mausoleum, cremation niches were broken (exposing urns), some urns had been removed from niches, and trash was scattered on the floor. [36]

As state officials combed through the cemetery's records, they discovered that Grand View had sold the same plot several times, [29] [38] disinterred bodies from graves and then resold the plots, disinterred bodies without state authorization, buried multiple bodies in a plot that should have held one person, and either failed to place markers on graves or willfully discarded or recycled markers. [30] [40] Advance purchase contracts for plots were inaccurate or incomplete. [40] They also discovered that Howard had removed $40,000 from the perpetual care trust fund as a "loan" but never repaid it. [30]

The CFB issued an order suspending all operations at Grand View Memorial Park. The cemetery was prohibited from selling new graves [30] or soliciting new business. [29] Burials could continue if already planned, or if planned for plots which had already been purchased. [29] Howard and Goldsman's state licenses to operate a cemetery were suspended, [29] and Howard was no longer permitted to act as the burial ground's superintendent. [30] The CFB launched a broader investigation into the cemetery's practices with an eye to turning over evidence to the Los Angeles County District Attorney for possible criminal prosecution. [29] Howard denied knowing that any cremated remains were being stored or that bodies had been improperly buried in the chapel. [29]

Those with loved ones buried at Grand View Memorial Park, and those who had purchased plot there, were outraged at the revelations, and within 10 days of the news had filed a numerous civil lawsuits against the cemetery in Los Angeles Superior Court. [30] [34] [k]

The CFB executed a search warrant against Grand View Memorial Park on November 2, 2005. [29] An examination of the cemetery's financial records indicated that Howard had commingled corporate funds with her personal assets and those of other businesses she owned. She used cemetery income to pay her personal bills and purchase items for her personal use. [36] [l] Inspectors also found some cemetery records had been destroyed. [40] The agency then accused Howard, Goldsman, and the cemetery as a corporation with 14 major violations of state law and regulations, including fraud, improper use of funds, mishandling of remains, negligence, and reselling graves. [31]

Closure and limited reopening

Although Howard had used the cemetery's caretaker lodge as her private residence for years, [36] [41] after November 5, 2005, she was barred by the CFB from entering the cemetery grounds. [29] She was left destitute by her suspension, lost her health insurance, and was able to pay for diabetic medication only after receiving financial help from a friend. She lived in her car, [27] as she was able to access the caretaker's lodge only during the day. When power was cut to the cemetery, Howard was forced to store her insulin (which required refrigeration) elsewhere. [27] Howard was found dead in the caretaker's lodge on November 4, 2006. [42] [43] She had long suffered from diabetes and emphysema [44] and was in very poor health. Her family did not express surprise at her demise. [42] A coroner later ruled that she had died from natural causes due to complications from her diabetes (acute diabetic ketoacidosis). [44] After Howard's death, her brother Tom Trimble inherited her estate. He was appointed special administrator of Grand View Memorial Park by a probate court the first week of January 2007. [41] [m]

Moshe Goldsman, the cemetery's minority owner, was appointed interim operator by the CFB. [38] [45] He closed Grand View Memorial Park to all visitors and family members on June 13, 2006, [42] after he was unable to pay the $40,000 to $50,000 a month ($62,390 to $77,988 in 2024 dollars) it took to pay employee salaries and the insurance, mortgage, and utility bills. [38]

The City of Glendale reopened Grand View Memorial Park to visitors on August 27, 2006. Thereafter, the city paid the cost for the cemetery to remain open each Sunday from noon to 4 PM. [42] The cost the city $31,000 a month ($48,352 in 2024 dollars). [46]

In October 2006, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Anthony Mohr placed Grand View Memorial Park under a preservation order, which barred anyone from altering or destroying the cemetery or any of its buildings, grounds, or contents. The following December, Judge Mohr placed a preservation of evidence order on the property to specifically protect any evidence relating to the ongoing lawsuit being pursued by aggrieved families. [41] On February 2, 2007, the first cremation interment was made at the cemetery since the suspension of its operating license on November 5, 2005. This was followed by the first full-body in-ground burial (in a two-person plot which already had one burial) in March 2007. The $2,000 ($3,033 in 2024 dollars) cost of burials were born by the individuals, as the cemetery was closed and could not provide staff or services. [34]

The City of Glendale voted in June 2007 to spend $187,600 ($284,486 in 2024 dollars) for maintenance and $79,800 ($121,013 in 2024 dollars) for staff to keep Grand View open from July 2007 to June 2008. By this time, the cemetery was in need of extensive maintenance. No irrigation, tree trimming, or weed control had occurred for more than a year. [35] [n] By August 2007, the city was facing a $400,000 ($454,935 in 2024 dollars) maintenance bill to make the cemetery safe for visitors. [47] California's extreme, ongoing drought had killed at least 36 trees, all of which were in danger of toppling. Another 200 trees were so badly damaged that they posed an immediate risk of dropping branches on visitors, and the lack of irrigation had rendered the entire cemetery an extreme fire hazard. [48] When other stakeholders balked at sharing the cost, the city won a public nuisance abatement order. Under existing law, this allowed the city to engage in maintenance activities at the site without the court or owners' consent in order to ensure that public health and safety were preserved. [47] The abatement order also allowed the city to pursue reimbursement from the owners at a later date. [48] [o]

Second closure and abatement

Winning the nuisance abatement order forced the full closure of Grand View Memorial Park, barring all families and visitors from the graveyard. Abatement work began on December 27, 2007. The entire cemetery was covered by an above-ground irrigation system, the knee-high grass was mowed, and the pruning and removal of trees began at an estimated cost of $105,400 ($154,074 in 2024 dollars). [50] [p] Four abandoned vehicles (including a hearse) were also removed, and repairs were made to all cemetery buildings to secure them against unauthorized entry. [52] [q] Goldman agreed to use accrued interest in the perpetual care fund to pay these costs. Although abatement was expected to end about the end of February 2008, neither the city nor Goldsman said if the cemetery would reopen. [50]

Some time after the initial abatement effort was completed, the Los Angeles Superior Court ordered Grand View Memorial Park opened every other Sunday and on holidays to allow visitation of graves. [53]

Legal issues

As legal proceedings against Grand View Memorial Park progressed, several families sought and won permission from the Superior Court to have their loved ones disinterred from the cemetery. In one case, a family discovered 10 to 20 cremated remains buried alongside a relative. [49]

By July 2007, the lawsuits against the cemetery were beginning to move forward. The court identified $6 million ($9,100,000 in 2024 dollars) in insurance and $20,000 to $40,000 ($30,329 to $60,658 in 2024 dollars) in perpetual care fund interest which could be used to settle the legal actions against Grand View. [45]

The cemetery owners, families, and the CFB settled part of the lawsuit at the end of August 2007. Moshe Goldsman, the sole remaining living stockholder, admitted to three violations of law, all of which concerned taking money from the perpetual care fund. To settle these claims, Goldsman agreed to sell the cemetery within three years and to reimburse the perpetual care fund $50,000 ($75,823 in 2024 dollars). [31]

The remainder of the legal proceedings against Grand View were settled in March 2010. By this time, all the lawsuits had been consolidated into a single class action. The agreement provided for the cemetery and its insurers to establish a $500,000 ($720,967 in 2024 dollars) fund for the restoration of the cemetery, pay $1.1 million ($1,600,000 in 2024 dollars) in legal fees, and pay $2.2 million ($3,200,000 in 2024 dollars) to the estimated 2,500 to 3,000 claimants harmed by the cemetery's actions. Paul Ayers, one of the lead attorneys for the plaintiffs, agreed to oversee the restoration, which included obtaining, cleaning, organizing, and possibly restoring cemetery records; identifying and properly interring all cremated remains; installing an in-ground irrigation system; and reseeding much of the cemetery's lawns. [53]

The restoration work began in December 2010, during which the cemetery was closed for 5 months, reopening on Memorial day weekend 2011. Using plans drawn up by a landscape architect, between $300,000 and $400,000 ($432,580 to $576,774 in 2024 dollars) was spent installing the permanent in-ground irrigation system and planting new trees, shrubs, and grass. The cemetery office was cleaned and a rodent-proof records storage space constructed, and the roof in the West Mausoleum was repaired. [51]

About the cemetery

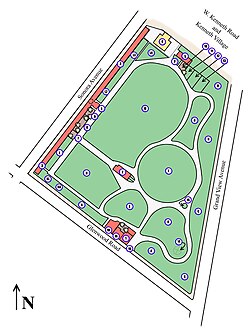

Grand View Memorial Park and Crematory is located at 1341 Glenwood Road in Glendale, California. The 25-acre (10 ha) cemetery [23] [49] has 112,000 spaces for interments. [38] About 44,000 spaces exist for in-ground, full-body burials; [49] the remaining spaces can accommodate only cremated remains. As of 2007, there were about 40,000 total burials at Grand View, and about 2,000 in-ground burial plots remained. [35] [49] [50] [r] There is unused space along W. Kenneth Road which could be used to expand in-ground burial space, and the roads in the cemetery could be narrowed to provide even more additional room. [35]

The cemetery has a very large West Mausoleum [51] running nearly the entire length of the site along Sonora Avenue, and a much smaller North Mausoleum near the entrance on W. Kenneth Road. [35] Section M is the largest section at Grand View Memorial Park and Crematory. Rows are often perpendicular to one another, but row markers are above-ground and aid in identifying the locations of plots. [55] The main mausoleum has above-ground and a below-ground floor. [36] The building in the cemetery's northern corner has been leased since about 2004 to St. Kevork Armenian Church, although it was formerly used for cemetery purposes. [47]

The cemetery perpetual care fund had a principal of about $1 million ($1,500,000 in 2024 dollars) in January 2008. At that time, the fund generated about $2,000 ($2,921 in 2024 dollars) in interest income each month, and the St. Kevork lease brought in another $1,200 ($1,753 in 2024 dollars) a month. [50]

The American Legion named Grand View Memorial its "official" burial site for veterans in 1923. [56] By 1949, about 200 active duty and retired members of the armed forces had been buried there. [57]

In 2006, Grand View Memorial Park had about a dozen employees. [38]