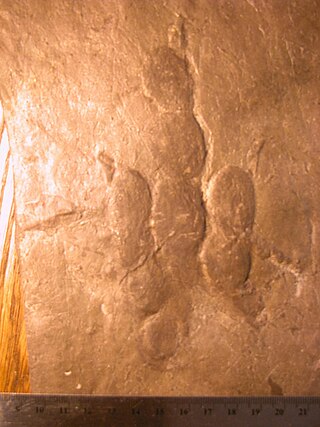

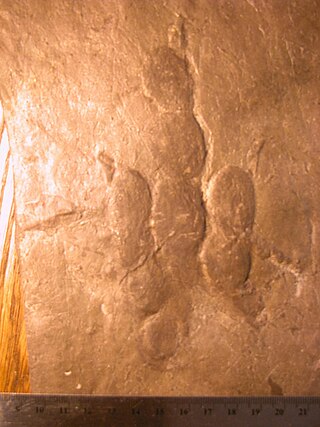

Grallator ["GRA-luh-tor"] is an ichnogenus which covers a common type of small, three-toed print made by a variety of bipedal theropod dinosaurs. Grallator-type footprints have been found in formations dating from the Early Triassic through to the early Cretaceous periods. They are found in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, Brazil and China, but are most abundant on the east coast of North America, especially the Triassic and Early Jurassic formations of the northern part of the Newark Supergroup. The name Grallator translates into "stilt walker", although the actual length and form of the trackmaking legs varied by species, usually unidentified. The related term "Grallae" is an ancient name for the presumed group of long-legged wading birds, such as storks and herons. These footprints were given this name by their discoverer, Edward Hitchcock, in 1858.

Gwyneddosaurus is a possibly invalid genus of extinct aquatic tanystropheid reptile. The type species, G. erici was described in 1945 by Wilhelm Bock, who identified it as a coelurosaurian dinosaur related to Podokesaurus. Its remains were found in the Upper Triassic Lockatong Formation of Montgomery County, eastern Pennsylvania, and the holotype includes skull fragments, several vertebra, ribs, gastralia, partial shoulder and hip bones, and several forelimb and hindlimb elements found in soft shale, while the paratype includes a femur and a tibia. The type specimen is ANSP 15072 and it was discovered by Bock's four-year-old son while the paratype is only listed as ?(ASNP coll.). It was not a large animal; the type skeleton was estimated by Bock as 18 centimetres (7.1 in) long, and its thigh bone was only 23 millimeters long (0.91 in).

The Triassic Lockatong Formation is a mapped bedrock unit in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. It is named after the Lockatong Creek in Hunterdon County, New Jersey.

The Purgatoire River track site, also called the Picketwire Canyonlands tracksite, is one of the largest dinosaur tracksites in North America. The site is located on public land of the Comanche National Grassland, along the Purgatoire ("Picketwire") River south of La Junta in Otero County, Colorado.

The Cow Branch Formation is a Late Triassic geologic formation in Virginia and North Carolina in the eastern United States. The formation consists of cyclical beds of black and grey lacustrine (lake) mudstone and shale. It is a konservat-lagerstätte renowned for its exceptionally preserved insect fossils, along with small reptiles, fish, and plants. Dinosaur tracks have also been reported from the formation.

Prorotodactylus is a dinosauromorph or pterosauromorph ichnogenus known from fossilized footprints found in Poland and France. The prints may have been made by a dinosauromorph that was a precursor to the dinosaurs, possibly closely related to Lagerpeton. Fossils of Prorotodactylus date back to the early Olenekian stage of the Early Triassic, making it the oldest known dinosauromorph. Its presence during this time extends the range of the dinosaur stem lineage to the start of the Early Triassic, soon after the Permian-Triassic extinction event. Prorotodactylus is the only ichnogenus within the ichnofamily Prorotodactylidae. Two ichnospecies are known, the type P. mirus and P. lutevensis.

Paleontology in Pennsylvania refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The geologic column of Pennsylvania spans from the Precambrian to Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Pennsylvania was submerged by a warm, shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The armored fish Palaeaspis appeared during the Silurian. By the Devonian the state was home to other kinds of fishes. On land, some of the world's oldest tetrapods left behind footprints that would later fossilize. Some of Pennsylvania's most important fossil finds were made in the state's Devonian rocks. Carboniferous Pennsylvania was a swampy environment covered by a wide variety of plants. The latter half of the period was called the Pennsylvanian in honor of the state's rich contemporary rock record. By the end of the Paleozoic the state was no longer so swampy. During the Mesozoic the state was home to dinosaurs and other kinds of reptiles, who left behind fossil footprints. Little is known about the early to mid Cenozoic of Pennsylvania, but during the Ice Age it seemed to have a tundra-like environment. Local Delaware people used to smoke mixtures of fossil bones and tobacco for good luck and to have wishes granted. By the late 1800s Pennsylvania was the site of formal scientific investigation of fossils. Around this time Hadrosaurus foulkii of neighboring New Jersey became the first mounted dinosaur skeleton exhibit at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The Devonian trilobite Phacops rana is the Pennsylvania state fossil.

Paleontology in Utah refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Utah. Utah has a rich fossil record spanning almost all of the geologic column. During the Precambrian, the area of northeastern Utah now occupied by the Uinta Mountains was a shallow sea which was home to simple microorganisms. During the early Paleozoic Utah was still largely covered in seawater. The state's Paleozoic seas would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, fishes, and trilobites. During the Permian the state came to resemble the Sahara desert and was home to amphibians, early relatives of mammals, and reptiles. During the Triassic about half of the state was covered by a sea home to creatures like the cephalopod Meekoceras, while dinosaurs whose footprints would later fossilize roamed the forests on land. Sand dunes returned during the Early Jurassic. During the Cretaceous the state was covered by the sea for the last time. The sea gave way to a complex of lakes during the Cenozoic era. Later, these lakes dissipated and the state was home to short-faced bears, bison, musk oxen, saber teeth, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. Formally trained scientists have been aware of local fossils since at least the late 19th century. Major local finds include the bonebeds of Dinosaur National Monument. The Jurassic dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis is the Utah state fossil.

Tanytrachelos is an extinct genus of tanystropheid archosauromorph reptile from the Late Triassic of the eastern United States. It contains a single species, Tanytrachelos ahynis, which is known from several hundred fossil specimens preserved in the Solite Quarry in Cascade, Virginia. Abundant fossils of Tanytrachelos are found in a series of lakebed sediments that were deposited over the course of about 350 thousand years in a lake which existed approximately 230 million years ago. Some fossils are very well-preserved and include the remains of soft tissues. Tanytrachelos is the most likely trackmaker of the ichnogenus Gwyneddichnium.

The Nugget Sandstone is a Late Triassic to Early Jurassic geologic formation that outcrops in Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah, western United States.

The 20th century in ichnology refers to advances made between the years 1900 and 1999 in the scientific study of trace fossils, the preserved record of the behavior and physiological processes of ancient life forms, especially fossil footprints. Significant fossil trackway discoveries began almost immediately after the start of the 20th century with the 1900 discovery at Ipolytarnoc, Hungary of a wide variety of bird and mammal footprints left behind during the early Miocene. Not long after, fossil Iguanodon footprints were discovered in Sussex, England, a discovery that probably served as the inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World.

Edward Hitchcock erected the ichnogenus Bifurculapes, meaning "two little forked feet," for trace fossils that were discovered in the Early Jurassic Turners Falls Formation in the Deerfield Basin of Massachusetts. They are insect or crustacean trackways that consist of two rows of two to three tracks per series, with the two larger tracks being oriented parallel or oblique to the trackway axis. The third track, when present, is much smaller than the other two and is oriented approximately perpendicular to the trackway axis. Medial drag marks sometimes are present between the track rows. In trace fossil classification schemes based on behavior, Bifurculapes is considered a repichnion, or locomotion trace. Getty (2020) considered Bifurculapes to represent locomotion under water based on the orientation of some trackways relative to sedimentary structures called current lineations.

This article records new taxa of trace fossils of every kind that are scheduled to be described during the year 2019, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to trace fossil paleontology that are scheduled to occur in the year 2019.

Dromopus is a reptilian ichnogenus commonly found in assemblages of ichnofossils dating to the late Pennsylvanian to the late Permian. It has been found throughout Europe, as well as in the United States, Canada, and Morocco. Several ichnospecies have been named; only the type ichnospecies D. lacertoides is definitively recognized.

Protochirotherium, also known as Protocheirotherium, is a Late Permian?-Early Triassic ichnotaxon consisting of five-fingered (pentadactyl) footprints and whole tracks, discovered in Germany and later Morocco, Poland and possibly also Italy. The type ichnospecies is P. wolfhagenense, discovered by R. Kunz in 1999 alongside Chirotherium tracks, was named and described in 2004 and re-evaluated in 2007; a second ichnospecies, P. hauboldi, also exists, which was initially described as an ichnospecies of Brachychirotherium. Protochirotherium-like prints have also been documented from the Late Permian of Italy, possibly representing the oldest known fossils of mesaxonic archosauromorphs.

Wakinyantanka is an ichnogenus of footprint produced by a large theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota. Wakinyantanka tracks are large with three long, slender toes with occasional impressions of a short hallux and narrow metatarsals. Wakinyantanka was the first dinosaur track to be discovered in the Hell Creek Formation, which remain rare in the preservational conditions of the rocks. The potential trackmakers may be a large oviraptorosaur or a small tyrannosaurid.

Brachychirotherium is an ichnogenus, a form taxon based on footprints. It is a type of chirothere, a term referring to the footprints of five-toed Triassic reptiles with a short fifth digit, leaving an appearance similar to a reverse human hand print. Brachychirotherium was first characterized from fossils found in Triassic beds in Germany, but has since been found in France, South Africa, Argentina, Peru, Bolivia, and North America.

Rhynchosauroides is an ichnogenus, a form taxon based on footprints. The organism producing the footprints was likely a lepidosaur and may have been a sphenodont, an ancestor of the modern tuatara. The footprint consists of five digits, of which the fifth is shortened and the first highly shortened.

Amphisauropus is an amphibian ichnogenus commonly found in assemblages of ichnofossils dating to the Permian to Triassic. It has been found in Europe, Morocco, and North America.

Batrachichnus is an amphibian ichnogenus commonly found in assemblages of ichnofossils dating to the Mississippian to Triassic of North America, South America, and Europe. The animal producing the tracks was likely a temnospondyl. B. slamandroides is the smallest known tetrapod footprint, produced by an animal with an estimated body length of just 8 millimeters (0.31 in)