Sauria is the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of Archosauria and Lepidosauria, and all its descendants. Since most molecular phylogenies recover turtles as more closely related to archosaurs than to lepidosaurs as part of Archelosauria, Sauria can be considered the crown group of diapsids, or reptiles in general. Depending on the systematics, Sauria includes all modern reptiles or most of them as well as various extinct groups.

Dinocephalosaurus is a genus of long necked, aquatic protorosaur that inhabited the Triassic seas of China. The genus contains the type and only known species, D. orientalis, which was named by Chun Li in 2003. Unlike other long-necked protorosaurs, Dinocephalosaurus convergently evolved a long neck not through elongation of individual neck vertebrae, but through the addition of neck vertebrae that each had a moderate length. As indicated by phylogenetic analyses, it belonged in a separate lineage that also included at least its closest relative Pectodens, which was named the Dinocephalosauridae in 2021. Like tanystropheids, however, Dinocephalosaurus probably used its long neck to hunt, utilizing the fang-like teeth of its jaws to ensnare prey; proposals that it employed suction feeding have not been universally accepted. It was probably a marine animal by necessity, as suggested by the poorly-ossified and paddle-like limbs which would have prevented it from going ashore.

Archosauromorpha is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs rather than lepidosaurs. Archosauromorphs first appeared during the late Middle Permian or Late Permian, though they became much more common and diverse during the Triassic period.

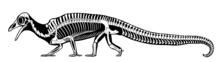

Tanystropheus is an extinct genus of archosauromorph reptile which lived during the Triassic Period in Europe, Asia, and North America. It is recognisable by its extremely elongated neck, longer than the torso and tail combined. The neck was composed of 13 vertebrae strengthened by extensive cervical ribs. Tanystropheus is one of the most well-described non-archosauriform archosauromorphs, known from numerous fossils, including nearly complete skeletons. Some species within the genus may have reached a total length of 6 meters (20 ft), making Tanystropheus the longest non-archosauriform archosauromorph as well. Tanystropheus is the namesake of the family Tanystropheidae, a clade collecting many long-necked Triassic archosauromorphs previously described as "protorosaurs" or "prolacertiforms".

Neodiapsida is a clade, or major branch, of the reptilian family tree, typically defined as including all diapsids apart from some early primitive types known as the araeoscelidians. Modern reptiles and birds belong to the neodiapsid subclade Sauria.

Protorosaurus is an extinct genus of reptile. Members of the genus lived during the late Permian period in what is now Germany and Great Britain. Once believed to have been an ancestor to lizards, Protorosaurus is now known to be one of the oldest and most primitive members of Archosauromorpha, the group that would eventually lead to archosaurs such as crocodilians and dinosaurs.

Avicephala is a potentially polyphyletic grouping of extinct diapsid reptiles that lived during the Late Permian and Triassic periods characterised by superficially bird-like skulls and arboreal lifestyles. As a clade, Avicephala is defined as including the gliding weigeltisaurids and the arboreal drepanosaurs to the exclusion of other major diapsid groups. This relationship is not recovered in the majority of phylogenetic analyses of early diapsids and so Avicephala is typically regarded as an artificial or unnatural grouping. However, the clade was recovered again in 2021 following a redescription of Weigeltisaurus, raising the possibility that the clade may be valid after all, although subsequent analyses have not supported this result.

Hovasaurus is an extinct genus of basal diapsid reptile. It lived in what is now Madagascar during the Late Permian and Early Triassic, being a survivor of the Permian–Triassic extinction event and the paleontologically youngest member of the Tangasauridae. Fossils have been found in the Permian Lower and Triassic Middle Sakamena Formations of the Sakamena Group, where it is amongst the commonest fossils. Its morphology suggests an aquatic ecology.

Megalancosaurus is a genus of extinct reptile from the Late Triassic Dolomia di Forni Formation and Zorzino Limestone of northern Italy, and one of the best known drepanosaurids. The type species is M. preonensis; a translation of the animal's scientific name would be "long armed reptile from the Preone Valley."

Hypuronector is a genus of extinct drepanosaur reptile from the Late Triassic Lockatong Formation of New Jersey. The etymology of the name translates as "deep-tailed swimmer from the lake", in reference to its assumed aquatic habits hypothesized by its discoverers. Hypuronector was related to the arboreal Megalancosaurus. It was a small animal, estimated to be only 12 cm (4.7 in) long in life. So far dozens of specimens of Hypuronector are known, though scientists have not found any complete skeletons. This makes attempts to reconstruct Hypuronector's body or lifestyle highly speculative and controversial.

Drepanosaurus is a genus of arboreal (tree-dwelling) reptile that lived during the Triassic Period. It is a member of the Drepanosauridae, a group of diapsid reptiles known for their prehensile tails. Drepanosaurus was probably an insectivore, and lived in a coastal environment in what is now modern day Italy, as well as in a streamside environment in the midwestern United States.

Vallesaurus is an extinct genus of Late Triassic elyurosaur drepanosauromorph. First found in Northern Italy in 1975, it is one of the most primitive drepanosaurs. V. cenenis is the type species, which was first mentioned in 1991 but only formally described in 2006. A second species, V. zorzinensis, was named in 2010.

Langobardisaurus is an extinct genus of tanystropheid archosauromorph reptile, with one valid species, L. pandolfii. Its fossils have been found in Italy and Austria, and it lived during the Late Triassic period, roughly 228 to 201 million years ago. Langobardisaurus was initially described in 1994, based on fossils from the Calcare di Zorzino Formation in Northern Italy. Fossils of the genus are also known from the Forni Dolostone of Northern Italy and the Seefeld Formation of Austria.

Helveticosaurus is an extinct genus of diapsid marine reptile known from the Middle Triassic of southern Switzerland. It contains a single species, Helveticosaurus zollingeri, known from the nearly complete holotype T 4352 collected at Cava Tre Fontane of Monte San Giorgio, an area well known for its rich record of marine life during the Middle Triassic.

Weigeltisauridae is a family of gliding neodiapsid reptiles that lived during the Late Permian, between 259.51 and 251.9 million years ago. Fossils of weigeltisaurids have been found in Madagascar, Germany, Great Britain, and Russia. They are characterized by long, hollow rod-shaped bones extending from the torso that probably supported wing-like membranes. Similar membranes are also found in several other extinct reptiles such as kuehneosaurids and Mecistotrachelos, as well as living gliding lizards, although each group evolved these structures independently.

Protorosauria is an extinct, likely paraphyletic group of basal archosauromorph reptiles from the latest Middle Permian to the end of the Late Triassic of Asia, Europe and North America. It was named by the English anatomist and paleontologist Thomas Henry Huxley in 1871 as an order, originally to solely contain Protorosaurus. Other names which were once considered equivalent to Protorosauria include Prolacertiformes and Prolacertilia.

Pamelaria is an extinct genus of allokotosaurian archosauromorph reptile known from a single species, Pamelaria dolichotrachela, from the Middle Triassic of India. Pamelaria has sprawling legs, a long neck, and a pointed skull with nostrils positioned at the very tip of the snout. Among early archosauromorphs, Pamelaria is most similar to Prolacerta from the Early Triassic of South Africa and Antarctica. Both have been placed in the family Prolacertidae. Pamelaria, Prolacerta, and various other Permo-Triassic reptiles such as Protorosaurus and Tanystropheus have often been placed in a group of archosauromorphs called Protorosauria, which was regarded as one of the most basal group of archosauromorphs. However, more recent phylogenetic analyses indicate that Pamelaria and Prolacerta are more closely related to Archosauriformes than are Protorosaurus, Tanystropheus, and other protorosaurs, making Protorosauria a polyphyletic grouping.

Allokotosauria is a clade of early archosauromorph reptiles from the Middle to Late Triassic known from Asia, Africa, North America and Europe. Allokotosauria was first described and named when a new monophyletic grouping of specialized herbivorous archosauromorphs was recovered by Sterling J. Nesbitt, John J. Flynn, Adam C. Pritchard, J. Michael Parrish, Lovasoa Ranivoharimanana and André R. Wyss in 2015. The name Allokotosauria is derived from Greek meaning "strange reptiles" in reference to unexpected grouping of early archosauromorph with a high disparity of features typically associated with herbivory.

Azendohsauridae is a family of allokotosaurian archosauromorphs that lived during the Middle to Late Triassic period, around 242-216 million years ago. The family was originally named solely for the eponymous Azendohsaurus, marking out its distinctiveness from other allokotosaurs, but as of 2022 the family now includes four other genera: the basal genus Pamelaria, the large horned herbivore Shringasaurus, and two carnivorous genera grouped into the subfamily-level subclade Malerisaurinae, Malerisaurus and Puercosuchus, and potentially also the dubious genus Otischalkia. Most fossils of azendohsaurids have a Gondwanan distribution, with multiple species known across Morocco and Madagascar in Africa as well as India, although fossils of malerisaurine azendohsaurids have also been found in the southwestern United States of North America.

Avicranium is a genus of extinct drepanosaur reptile known from the Chinle Formation of the late Triassic. The type species of Avicranium is Avicranium renestoi. "Avicranium" is Latin for "bird cranium", in reference to its unusual bird-like skull, while "renestoi" references Silvio Renesto, a paleontologist known for studies of Italian drepanosaurs.