Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron, copper, silver, tin, lead and zinc. Smelting uses heat and a chemical reducing agent to decompose the ore, driving off other elements as gases or slag and leaving the metal behind. The reducing agent is commonly a fossil-fuel source of carbon, such as carbon monoxide from incomplete combustion of coke—or, in earlier times, of charcoal. The oxygen in the ore binds to carbon at high temperatures, as the chemical potential energy of the bonds in carbon dioxide is lower than that of the bonds in the ore.

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content in contrast to that of cast iron. It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions, which give it a wood-like "grain" that is visible when it is etched, rusted, or bent to failure. Wrought iron is tough, malleable, ductile, corrosion resistant, and easily forge welded, but is more difficult to weld electrically.

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. Blast refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

Bog iron is a form of impure iron deposit that develops in bogs or swamps by the chemical or biochemical oxidation of iron carried in solution. In general, bog ores consist primarily of iron oxyhydroxides, commonly goethite.

The Wealden iron industry was located in the Weald of south-eastern England. It was formerly an important industry, producing a large proportion of the bar iron made in England in the 16th century and most British cannon until about 1770. Ironmaking in the Weald used ironstone from various clay beds, and was fuelled by charcoal made from trees in the heavily wooded landscape. The industry in the Weald declined when ironmaking began to be fuelled by coke made from coal, which does not occur accessibly in the area.

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a bloom. The mix of slag and iron in the bloom, termed sponge iron, is usually consolidated and further forged into wrought iron. Blast furnaces, which produce pig iron, have largely superseded bloomeries.

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation. Finery forges were used as early as the 3rd century BC in China. The finery forge process was replaced by the puddling process and the roller mill, both developed by Henry Cort in 1783–4, but not becoming widespread until after 1800.

A stamp mill is a type of mill machine that crushes material by pounding rather than grinding, either for further processing or for extraction of metallic ores. Breaking material down is a type of unit operation.

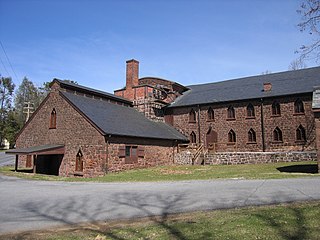

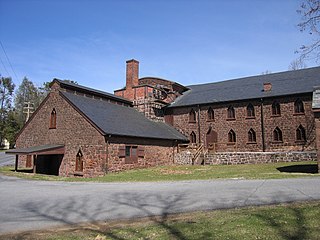

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a designated National Historic Landmark that is administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania in the United States. The furnace was a leading Pennsylvania iron producer from 1742 until it was shut down in 1883. The furnaces, support buildings and surrounding community have been preserved as a historical site and museum, providing a glimpse into Lebanon County's industrial past. The site is the only intact charcoal-burning iron blast furnace in its original plantation in the Western Hemisphere. Established by Peter Grubb in 1742, Cornwall Furnace was operated during the American Revolution by his sons Curtis and Peter Jr. who were major arms providers to George Washington. Robert Coleman acquired Cornwall Furnace after the Revolution and became Pennsylvania's first millionaire. Ownership of the furnace and its surroundings was transferred to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1932.

Schmidmühlen is a municipality in the district of Amberg-Sulzbach in Bavaria in Germany. It is situated at the junction of the Vils and Lauterach rivers.

Fichtelberg is a municipality in the district of Bayreuth in Bavaria in Germany. It is a state-recognised climatic spa (Luftkurort).

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor, Syria and Greece; by the end of the Emperor Trajan's reign, the Roman Empire had grown further to encompass parts of Britain, Egypt, all of modern Germany west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum, Judea, Armenia, Illyria, and Thrace. As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.

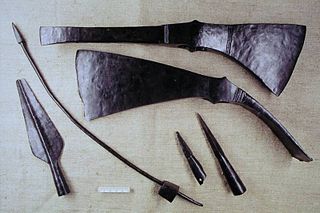

Archaeometallurgical slag is slag discovered and studied in the context of archaeology. Slag, the byproduct of iron-working processes such as smelting or smithing, is left at the iron-working site rather than being moved away with the product. As it weathers well, it is readily available for study. The size, shape, chemical composition and microstructure of slag are determined by features of the iron-working processes used at the time of its formation.

Mining in the Upper Harz region of central Germany was a major industry for several centuries, especially for the production of silver, lead, copper, and, latterly, zinc as well. Great wealth was accumulated from the mining of silver from the 16th to the 19th centuries, as well as from important technical inventions. The centre of the mining industry was the group of seven Upper Harz mining towns of Clausthal, Zellerfeld, Sankt Andreasberg, Wildemann, Grund, Lautenthal und Altenau.

The Erzberg mine is a large open-pit mine located in Eisenerz, Styria, in the central-western part of Austria, 60 km north-west of Graz and 260 km south-west of the capital, Vienna. The deposit lies at the Northern fringes of the Eastern greywacke zone, a band of Paleozoic metamorphosed sedimentary rocks that run east-west through the Austrian Alps, rich in copper and iron ore. Erzberg is the largest iron ore reserves in Austria, having estimated reserves of 235 million tonnes of ore. The mine produces around 3.2 million tonnes of pure iron ore per year. It is also the site of the annual Erzberg Rodeo hard enduro motorbike race.

Frohnau is a village in the Saxon town of Annaberg-Buchholz in the district of Erzgebirgskreis in southeast Germany. The discovery of silver on the Schreckenberg led in 1496 to the foundation of the neighbouring mining town of Annaberg. The village of Frohnau is best known for its museum of technology, the Frohnauer Hammer, and the visitor mine of Markus Röhling Stolln. The mining area around Frohnau has been selected as a candidate for a UNESCO World Heritage Site: the Ore Mountain Mining Region.

Eisenhammer Dorfchemnitz is an historic hammer mill in Dorfchemnitz in the Ore Mountains of Germany. The mill is an important witness to proto-industrial development in the Ore Mountains. Of the once-numerous hammer mills only three others remain working in Saxony apart from the Frohnauer Hammer: the Frohnauer Hammer Mill, the Grünthal Copper Hammer Mill and the Freibergsdorf Hammer Mill.

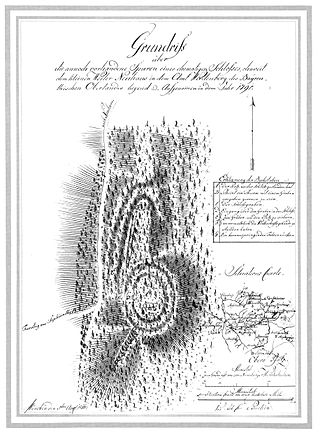

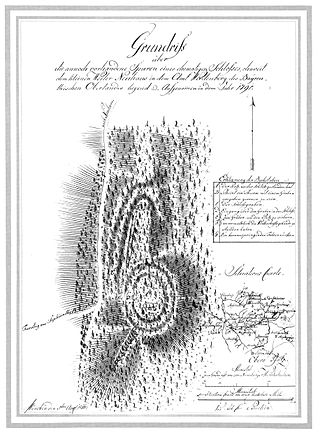

The Burgstall of Schlosshügel near Weidenberg is a lost hill castle or circular rampart site of the type known as a motte from the Early Middle Ages. It lies on the southern perimeter of the Fichtel Mountains at a height of 699 metres above sea level (NN) above the village of Sophienthal, which is part of the market borough of Weidenberg in the Upper Franconia county of Bayreuth in Bavaria. The burgstall or lost castle site was partly investigated by means of an archaeological test excavation and was also mapped several times in the past.

Rothe Erde is a district of Aachen, Germany with large-scale development in heavy industry. It is sub-district 34 of the Aachen-Mitte Stadtbezirk. It lies between the districts of Forst and Eilendorf.

Rittersgrün is a district of the municipality of Breitenbrunn/Erzgeb. in the Saxon Erzgebirge district. The scattered settlement with around 1600 inhabitants grew up around several hammer mills, which operated on the course of the Pöhlwasser from the 15th to the 19th century and were supplied with ore from numerous surrounding mines. Due to its location on an important Erzgebirge pass, the settlement was repeatedly plundered by passing mercenaries during the Thirty Years' War. After the decline of the hammer mill industry in the middle of the 19th century, the village's economy was dominated by cardboard and sawmills. In 2007, Rittersgrün was incorporated into Breitenbrunn/Erzgeb. Today, Rittersgrün is primarily known as an excursion and winter sports resort. The main attractions include the Saxon Narrow Gauge Railway Museum and a well-developed network of hiking trails.