The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, received its enabling act of Parliament on 31 August 1835 and ran its first trains in 1838 with the initial route completed between London and Bristol in 1841. It was engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who chose a broad gauge of 7 ft —later slightly widened to 7 ft 1⁄4 in —but, from 1854, a series of amalgamations saw it also operate 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in standard-gauge trains; the last broad-gauge services were operated in 1892.

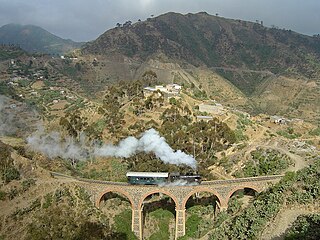

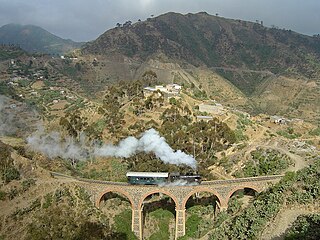

The Eritrean Railway is the only railway system in Eritrea. It was constructed between 1887 and 1932 during the Italian Eritrea colony and connects the port of Massawa with Asmara. Originally it also connected to Bishia. The line was partly damaged by warfare in subsequent decades, but was rebuilt in the 1990s. Vintage equipment is still used on the line.

A Fairlie locomotive is a type of articulated steam locomotive that has the driving wheels on bogies. The locomotive may be double-ended or single ended.

The Metropolitan Railway was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex suburbs. Its first line connected the main-line railway termini at Paddington, Euston, and King's Cross to the City. The first section was built beneath the New Road using cut-and-cover between Paddington and King's Cross and in tunnel and cuttings beside Farringdon Road from King's Cross to near Smithfield, near the City. It opened to the public on 10 January 1863 with gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, the world's first passenger-carrying designated underground railway.

Bilton is a suburb of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, situated to the north-east of the town centre.

The North Coast railway line (NCL) is a 1,681-kilometre (1,045 mi) 1067 mm gauge railway line in Queensland, Australia. It commences at Roma Street station, Brisbane, and largely parallels the Queensland coast to Cairns in Far North Queensland. The line is electrified between Brisbane and Rockhampton. Along the way, the 1680 km railway passes through the numerous towns and cities of eastern Queensland including Nambour, Bundaberg, Gladstone, Rockhampton, Mackay and Townsville. The line though the centre of Rockhampton runs down the middle of Denison Street.

The Kalka–Shimla Railway is a 2 ft 6 in narrow-gauge railway in North India which traverses a mostly mountainous route from Kalka to Shimla. It is known for dramatic views of the hills and surrounding villages. The railway was built under the direction of Herbert Septimus Harington between 1898 and 1903 to connect Shimla, the summer capital of India during the British Raj, with the rest of the Indian rail system.

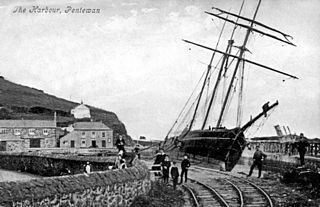

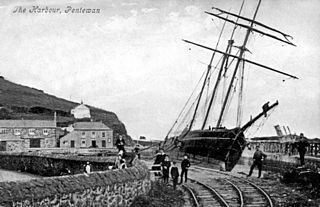

The Pentewan Railway was a 2 ft 6 in narrow gauge railway in Cornwall, England. It was built as a horse-drawn tramway carrying china clay from St Austell to a new harbour at Pentewan, and was opened in 1829. In 1874 the line was strengthened for locomotive working. It finally succumbed to more efficient operation at other ports and closed in 1918.

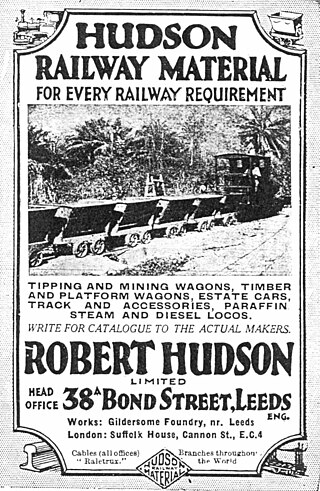

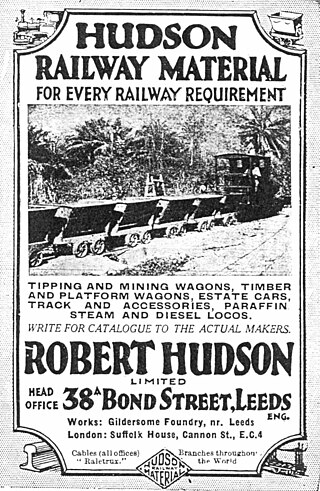

Robert Hudson Ltd was a major international supplier of light railway materials, based in Gildersome, near Leeds, England. The name was later changed to Robert Hudson (Raletrux) Ltd.

The Lochaber Narrow Gauge Railway was a 3 ft narrow-gauge industrial railway. It was a relatively long line, built for the construction and subsequent maintenance of a 15-mile-long (24-kilometre) tunnel from Loch Treig to a factory near Fort William in Scotland. The tunnel was excavated to carry water for the Lochaber hydroelectric scheme in connection with aluminium production by British Aluminium. The railway came to be known colloquially as the 'Old Puggy Line'.

The Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway was an early mineral railway running from a colliery at Monklands to the Forth and Clyde Canal at Kirkintilloch, Scotland. It was the first railway to use a rail ferry, the first public railway in Scotland, and the first in Scotland to use locomotive power successfully, and it had a great influence on the successful development of the Lanarkshire iron industry. It opened in 1826.

The Wishaw and Coltness Railway was an early Scottish mineral railway. It ran for approximately 11 miles from Chapel Colliery, at Newmains in North Lanarkshire connecting to the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway near Whifflet, giving a means of transport for minerals around Newmains to market in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

A trench railway was a type of railway that represented military adaptation of early 20th-century railway technology to the problem of keeping soldiers supplied during the static trench warfare phase of World War I. The large concentrations of soldiers and artillery at the front lines required delivery of enormous quantities of food, ammunition and fortification construction materials where transport facilities had been destroyed. Reconstruction of conventional roads and railways was too slow, and fixed facilities were attractive targets for enemy artillery. Trench railways linked the front with standard gauge railway facilities beyond the range of enemy artillery. Empty cars often carried litters returning wounded from the front.

Angerstein Wharf is an industrial area and location of a marine construction aggregate and an associated cement facility and freight station in the Port of London, operated by the Cemex company, located on the south bank of the Bugsby's Reach of the River Thames in both Greenwich and Charlton, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. It has safeguarded wharf status.

The Forest of Dean Railway was a railway company operating in Gloucestershire, England. It was formed in 1826 when the moribund Bullo Pill Railway and a connected private railway failed, and they were purchased by the new company. At this stage it was a horse-drawn plateway, charging a toll for private hauliers to use it with horse traction. The traffic was chiefly minerals from the Forest of Dean, in the Whimsey and Churchway areas, near modern-day Cinderford, for onward conveyance from Bullo Pill at first, and later by the Great Western Railway.

The Astley and Tyldesley Collieries Company formed in 1900 owned coal mines on the Lancashire Coalfield south of the railway in Astley and Tyldesley, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England. The company became part of Manchester Collieries in 1929 and some of its collieries were nationalised in 1947.

The Avon and Gloucestershire Railway also known as The Dramway was an early mineral railway, built to bring coal from pits in the Coalpit Heath area, north-east of Bristol, to the River Avon opposite Keynsham. It was dependent on another line for access to the majority of the pits, and after early success, bad relations and falling traffic potential dogged most of its existence.

The United Verde and Pacific Railway was a 3 ft narrow gauge railroad that operated from 1895 to 1920 in what became Yavapai County in the U.S. state of Arizona. William A. Clark built the 26-mile (42 km) line to link his copper mine and smelter in Jerome to an existing branch of the Santa Fe Railway system. Clark eventually replaced the line with three 4 ft 8+1⁄2 instandard gauge rail lines after building a new smelter and company town in Clarkdale.

The Hampton Kempton Waterworks Railway is a 2 ft gauge narrow gauge steam railway that opened in 2013, giving rides to paying visitors on a restored steam locomotive, with two back-up diesel locomotives. It is based on the site of an industrial railway that served Kempton Waterworks.

The Colsterdale Light Railway (CLR) was a narrow-gauge railway line in Colsterdale, North Yorkshire, England. It was built between 1903 and 1905 to allow materials to be taken up the Colsterdale valley for reservoir building. The building of two reservoirs in the valley of the River Burn, was first approved for the councils of Harrogate and Leeds respectively in 1901. Construction on the second reservoir was halted during the First World War, although the railway was kept in use carrying men and supplies to the training camp, later a PoW camp, at Breary Banks.