The Gospel of Mark is the second of the four canonical gospels and of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells of the ministry of Jesus from his baptism by John the Baptist to his death, burial, and the discovery of his empty tomb. There is no miraculous birth or doctrine of divine pre-existence, nor, in the original ending, any post-resurrection appearances of Jesus. It portrays Jesus as a teacher, an exorcist, a healer, and a miracle worker. He refers to himself as the Son of Man. He is called the Son of God, but keeps his messianic nature secret; even his disciples fail to understand him. All this is in keeping with Christian interpretation of prophecy, which is believed to foretell the fate of the messiah as suffering servant. The gospel ends, in its original version, with the discovery of the empty tomb, a promise to meet again in Galilee, and an unheeded instruction to spread the good news of the Resurrection of Jesus.

The Gospel of Luke tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts, accounting for 27.5% of the New Testament. The combined work divides the history of first-century Christianity into three stages, with the gospel making up the first two of these – the life of Jesus the Messiah from his birth to the beginning of his mission in the meeting with John the Baptist, followed by his ministry with events such as the Sermon on the Plain and its Beatitudes, and his Passion, death, and resurrection.

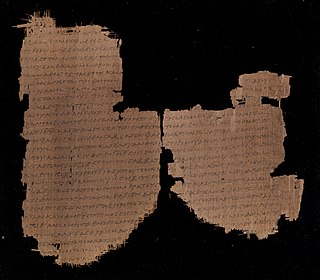

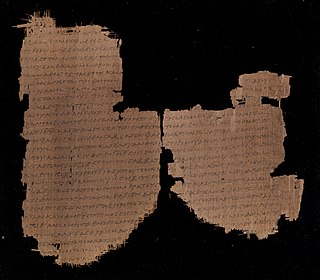

Gospel originally meant the Christian message, but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words and deeds of Jesus, culminating in his trial and death and concluding with various reports of his post-resurrection appearances. Modern scholars are cautious of relying on the gospels uncritically, but nevertheless, they provide a good idea of the public career of Jesus, and critical study can attempt to distinguish the original ideas of Jesus from those of the later authors.

Mary Magdalene was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. She is mentioned by name twelve times in the canonical gospels, more than most of the apostles and more than any other woman in the gospels, other than Jesus's family. Mary's epithet Magdalene may mean that she came from the town of Magdala, a fishing town on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in Roman Judea.

The resurrection of Jesus is the Christian belief that God raised Jesus on the third day after his crucifixion, starting – or restoring – his exalted life as Christ and Lord. According to the New Testament writing, Jesus was firstborn from the dead, ushering in the Kingdom of God. He appeared to his disciples, calling the apostles to the Great Commission of proclaiming the Gospel of eternal salvation through his death and resurrection, and ascended to Heaven.

The Last Supper is the final meal that, in the Gospel accounts, Jesus shared with his apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion. The Last Supper is commemorated by Christians especially on Holy Thursday. The Last Supper provides the scriptural basis for the Eucharist, also known as "Holy Communion" or "The Lord's Supper".

The empty tomb is the Christian tradition that the tomb of Jesus was found empty on the third day after his crucifixion. All four canonical gospels relay the story, but beyond a basic outline, they agree on little.

Jesus is the Son of God and in mainstream Christian denominations he is God the Son, the second Person in the Trinity. He is believed to be the Jewish messiah who is prophesied in the Hebrew Bible, which is called the Old Testament in Christianity. Through his crucifixion and subsequent resurrection, God offered humans salvation and eternal life, that Jesus died to atone for sin to make humanity right with God.

Jewish Christians were the followers of a Jewish religious sect that emerged in Judea during the late Second Temple period. The Nazarene Jews integrated the belief of Jesus as the prophesied Messiah and his teachings into the Jewish faith, including the observance of the Jewish law. The name may derive from the city of Nazareth, or from prophecies in Isaiah and elsewhere where the verb occurs as a descriptive plural noun, or from both. Jewish Christianity is the foundation of Early Christianity, which later developed into Christianity. Christianity started with Jewish eschatological expectations, and it developed into the worship of a deified Jesus after his earthly ministry, his crucifixion, and the post-crucifixion experiences of his followers. Modern scholarship is engaged in an ongoing debate as to the proper designation for Jesus' first followers. Many see the term Jewish Christians as anachronistic given that there is no consensus on the date of the birth of Christianity. Some modern scholars have suggested the designations "Jewish believers in Jesus" or "Jewish followers of Jesus" as better reflecting the original context.

Jesus, also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth, was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the central figure of Christianity, the world's largest religion. Most Christians believe he is the incarnation of God the Son and the awaited Messiah prophesied in the Hebrew Bible.

The life of Jesus in the New Testament is primarily outlined in the four canonical gospels, which includes his genealogy and nativity, public ministry, passion, prophecy, resurrection and ascension. Other parts of the New Testament – such as the Pauline epistles which were likely written within 20 to 30 years of each other, and which include references to key episodes in Jesus' life, such as the Last Supper, and the Acts of the Apostles, which includes more references to the Ascension episode than the canonical gospels – also expound upon the life of Jesus. In addition to these biblical texts, there are extra-biblical texts that Christians believe make reference to certain events in the life of Jesus, such as Josephus on Jesus and Tacitus on Christ.

The stolen body hypothesis posits that the body of Jesus Christ was stolen from his burial place. His tomb was found empty not because he was resurrected, but because the body had been hidden somewhere else by the apostles or unknown persons. Both the stolen body hypothesis and the debate over it presume the basic historicity of the gospel accounts of the tomb discovery. The stolen body hypothesis finds the idea that the body was not in the tomb plausible – such a claim could be checked if early Christians made it – but considers it more likely that early Christians had been misled into believing the resurrection by the theft of Jesus's body.

The vision theory or vision hypothesis is a term used to cover a range of theories that question the physical resurrection of Jesus, and suggest that sightings of a risen Jesus were visionary experiences. It was first formulated by David Friedrich Strauss in the 19th century, and has been proposed in several forms by critical contemporary scholarship, including Helmut Koester, Géza Vermes, and Larry Hurtado, and members of the Jesus Seminar such as Gerd Lüdemann.

The post-resurrection appearances of Jesus in the canonical gospels are reported to have occurred after Jesus' death, burial and resurrection, but prior to his ascension. Among these sources, most scholars believe the First Epistle to the Corinthians was written first. Most Christians point to the appearances as evidence of his bodily resurrection and identity as Messiah, seated in Heaven on the right hand of God. Others, including Liberal Christians, interpret these accounts as visionary experiences.

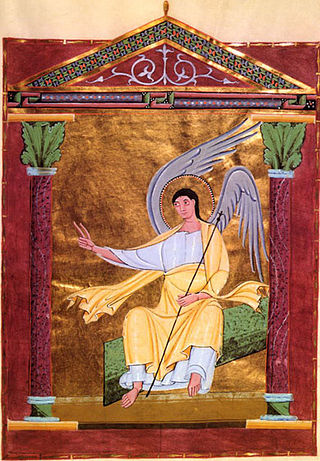

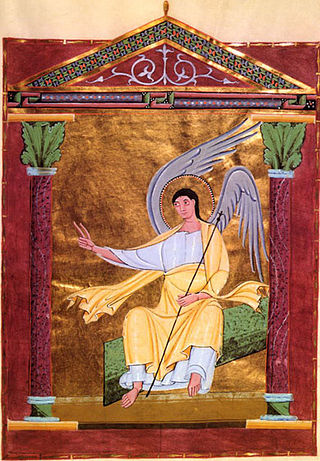

In Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition the Myrrhbearers are the individuals mentioned in the New Testament who were directly involved in the burial or who discovered the empty tomb following the resurrection of Jesus. The term traditionally refers to the women with myrrh who came to the tomb of Christ early in the morning to find it empty. In Western Christianity, the two women at the tomb, the Three Marys or other variants are the terms normally used. Also included are Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, who took the body of Jesus down from the cross, embalmed it with myrrh and aloes, wrapped it in clean linen, and placed it in a new tomb..

1 Corinthians 15 is the fifteenth chapter of the First Epistle to the Corinthians in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It is authored by Paul the Apostle and Sosthenes in Ephesus. The first eleven verses contain the earliest account of the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus in the New Testament. The rest of the chapter stresses the primacy of the resurrection for Christianity.

The burial of Jesus refers to the burial of the body of Jesus after crucifixion, before the eve of the sabbath described in the New Testament. According to the canonical gospel accounts, he was placed in a tomb by a councillor of the sanhedrin named Joseph of Arimathea. In art, it is often called the Entombment of Christ.

Christianity in the 1st century covers the formative history of Christianity from the start of the ministry of Jesus to the death of the last of the Twelve Apostles and is thus also known as the Apostolic Age. Early Christianity developed out of the eschatological ministry of Jesus. Subsequent to Jesus' death, his earliest followers formed an apocalyptic messianic Jewish sect during the late Second Temple period of the 1st century. Initially believing that Jesus' resurrection was the start of the end time, their beliefs soon changed in the expected Second Coming of Jesus and the start of God's Kingdom at a later point in time.

The historical reliability of the Gospels is the reliability and historic character of the four New Testament gospels as historical documents. While all four canonical gospels contain some sayings and events which may meet one or more of the five criteria for historical reliability used in biblical studies, the assessment and evaluation of these elements is a matter of ongoing debate. Virtually all scholars of antiquity agree that a human Jesus existed, but scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the biblical accounts of Jesus, and the only two events subject to "almost universal assent" are that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and was crucified by the order of the Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate. Elements whose historical authenticity is disputed include the two accounts of the Nativity of Jesus, the miraculous events including the resurrection, and certain details about the crucifixion.

Scholars have given various interpretations of the elements of the Gospel stories.