The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly 1,500 km (930 mi) long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at 2,500 km (1,600 mi) and the Scandinavian Mountains at 1,700 km (1,100 mi). The range stretches from the far eastern Czech Republic (3%) and Austria (1%) in the northwest through Slovakia (21%), Poland (10%), Ukraine (10%), Romania (50%) to Serbia (5%) in the south. The highest range within the Carpathians is known as the Tatra mountains in Poland and Slovakia, where the highest peaks exceed 2,600 m (8,500 ft). The second-highest range is the Southern Carpathians in Romania, where the highest peaks range between 2,500 m (8,200 ft) and 2,550 m (8,370 ft).

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa, is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. It was once called "the most Hungarian river" because it used to flow entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national borders.

Vipera berus, also known as the common European adder and the common European viper, is a species of venomous snake in the family Viperidae. The species is extremely widespread and can be found throughout much of Europe, and as far as East Asia. There are three recognised subspecies.

Lake Neusiedl, or Fertő, is the largest endorheic lake in Central Europe, straddling the Austrian–Hungarian border. The lake covers 315 km2 (122 sq mi), of which 240 km2 (93 sq mi) is on the Austrian side and 75 km2 (29 sq mi) on the Hungarian side. The lake's drainage basin has an area of about 1,120 km2 (430 sq mi). From north to south, the lake is about 36 km (22 mi) long, and it is between 6 km and 12 km wide from east to west. On average, the lake's surface is 115.45 m (378.8 ft) above the Adriatic Sea and the lake is no more than 1.8 m deep.

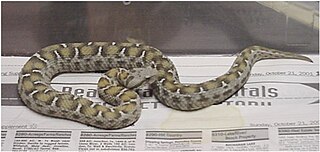

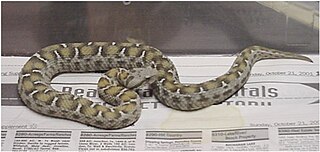

Macrovipera lebetinus, known as the blunt-nosed viper, Lebetine viper, Levant viper, and by other common names, is a viper species found in North Africa, much of the Middle East, and as far east as Kashmir. Like all other vipers, it is venomous. Five subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate race described here.

Vipera aspis is a viper species found in southwestern Europe. Its common names include asp, asp viper, European asp, and aspic viper, among others. Like all other vipers, it is venomous. Bites from this species can be more severe than from the European adder, V. berus; not only can they be very painful, but approximately 4% of all untreated bites are fatal. The specific epithet, aspis, is a Greek word that means "viper." Five subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.

Montivipera albizona, the central Turkish mountain viper, is a viper species endemic to the mountainous regions of central Turkey. Like all other vipers, it is venomous. No subspecies are currently recognized.

Vipera kaznakovi, known as the Caucasus viper, Kaznakow's viper, Kaznakov's viper, and by other common names, is a species of venomous snake in the subfamily Viperinae of the family Viperidae. The species is endemic to Turkey, Georgia, and Russia. No subspecies are currently recognized.

Vipera latastei, known as Lataste's viper, the snub-nosed viper, and the snub-nosed adder, is a species of venomous snake in the subfamily Viperinae of the family Viperidae. The species is endemic to the Iberian Peninsula and northwestern Maghreb. Three extant subspecies and one extinct subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.

Daboia palaestinae, also known as the Palestine viper, is a viper species endemic to the Levant. Like all vipers, it is venomous. It is considered a leading cause of snakebite within its range. No subspecies are currently recognized.

Vipera seoanei is a venomous viper species endemic to extreme southwestern France and the northern regions of Spain and Portugal. Two subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate race described here.

Vipera ursinii is a species of venomous snake in the subfamily Viperinae of the family Viperidae. It is a very rare species, which is in danger of extinction. This species is commonly called the meadow viper. It is found in France, Italy, and Greece as well as much of eastern Europe. Several subspecies are recognized. Beyond the highly threatened European population, poorly known populations exist as far to the east as Kazakhstan and northwestern China.

Vipera renardi is a species of viper, a venomous snake in the family Viperidae. The species is endemic to Asia and Eastern Europe. Five subspecies are recognized.

Wagner's viper, known as the ocellate mountain viper, ocellated mountain viper, and Wagner's viper, is a species of venomous snake in the subfamily Viperinae of the family Viperidae. The species is native to eastern Turkey and northwestern Iran. There are no subspecies that are recognized as being valid.

Montivipera xanthina, known as the rock viper, coastal viper, Ottoman viper, and by other common names, is a viper species found in northeastern Greece and Turkey, as well as certain islands in the Aegean Sea. Like all other vipers, it is venomous. No subspecies are currently recognized.

The Hungarian Ornithological and Nature Conservation Society (MME), also known as BirdLife Hungary, is a non-profit ornithological and nature conservation organisation founded in Hungary in 1974. Its mission is to protect wild birds and help preserve biodiversity. It has about 10,000 members, employs 26 staff, and is the Hungarian partner organisation of BirdLife International. Since 1991 it has published the journal Ornis Hungarica.

Vipera walser, the Walser viper or Piedmont viper is a viper endemic to the western Italian Alps. While long considered as an isolated population of Vipera berus, molecular analyses have shown it to be a distinct species related to the Vipera ursinii-complex.

Vipera graeca, commonly known as the Greek meadow viper, is a species of viper found in Albania and Greece, named after its presence in Greek meadows. As with all vipers, the Greek viper is venomous. The Greek viper was previously thought to be a subspecies of Vipera ursinii, but was elevated to species status as it has many morphological and molecular differences.