The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, became disqualified to inherit the throne. This had the effect of deposing the remaining descendants of Charles I, other than his Protestant granddaughter Anne, as the next Protestant in line to the throne was Sophia of Hanover. Born into the House of Wittelsbach, she was a granddaughter of James VI and I from his most junior surviving line, with the crowns descending only to her non-Catholic heirs. Sophia died shortly before the death of Queen Anne, and Sophia's son succeeded to the throne as King George I, starting the Hanoverian dynasty in Britain.

The politics of Norway take place in the framework of a parliamentary, representative democratic constitutional monarchy. Executive power is exercised by the Council of State, the cabinet, led by the prime minister of Norway. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the legislature, the Storting, elected within a multi-party system. The judiciary is independent of the executive branch and the legislature.

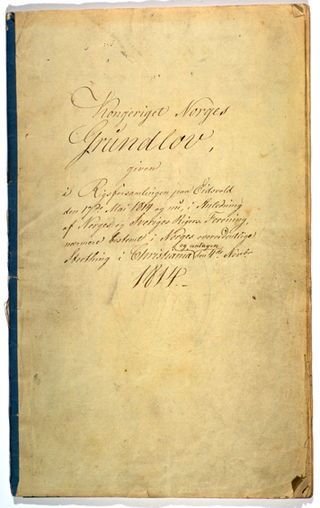

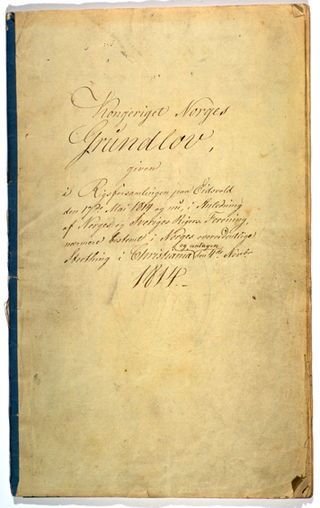

The Constitution of Norway was adopted on 16 May and signed on 17 May 1814 by the Norwegian Constituent Assembly at Eidsvoll. The latter date is the National Day of Norway; it marks the establishment of the constitution.

The Storting is the supreme legislature of Norway, established in 1814 by the Constitution of Norway. It is located in Oslo. The unicameral parliament has 169 members and is elected every four years based on party-list proportional representation in nineteen multi-seat constituencies. A member of Stortinget is known in Norwegian as a stortingsrepresentant, literally "Storting representative".

The history of Jews in Norway dates back to the 1400s. Although there were very likely Jewish merchants, sailors and others who entered Norway during the Middle Ages, no efforts were made to establish a Jewish community. Through the early modern period, Norway, still devastated by the Black Death, was ruled by Denmark from 1536 to 1814 and then by Sweden until 1905. In 1687, Christian V rescinded all Jewish privileges, specifically banning Jews from Norway, except with a special dispensation. Jews found in the kingdom were jailed and expelled, and this ban persisted until 1851.

Carl Joachim Hambro was a Norwegian journalist, author and leading politician representing the Conservative Party. A ten-term member of the Parliament of Norway, Hambro served as President of the Parliament for 20 of his 38 years in the legislature. He was actively engaged in international affairs, including work with the League of Nations (1939–1940), delegate to the UN General Assembly (1945–1956) and member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee (1940–1963).

Religion in Norway is dominated by Lutheran Christianity, with 68.7% of the population belonging to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Norway in 2019. The Catholic Church is the next largest Christian church at 3.1%. The unaffiliated make up 18.3% of the population. Islam is followed by 3.4% of the population.

In 1814, the Kingdom of Norway made a brief and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to regain its independence. While Norway had always legally been a separate kingdom, since the 16th century it had shared a monarch with Denmark; Norway was a subordinate partner in the combined state, whose government was based in Copenhagen. Due to its alliance with France during the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark was forced to sign the Treaty of Kiel in January 1814 ceding Norway to Sweden.

Religious education is the term given to education concerned with religion. It may refer to education provided by a church or religious organization, for instruction in doctrine and faith, or for education in various aspects of religion, but without explicitly religious or moral aims, e.g. in a school or college. The term is often known as religious studies.

The Catholic Church in the Nordic countries was the only Christian church in that region before the Reformation in the 16th century. Since then, Scandinavia has been a mostly non-Catholic (Lutheran) region and the position of Nordic Catholics for many centuries after the Reformation was very difficult due to legislation outlawing Catholicism. However, the Catholic population of the Nordic countries has seen some growth in the region in recent years, particularly in Norway, in large part due to immigration and to a lesser extent conversions among the native population.

The Norwegian Constituent Assembly is the name given to the 1814 constitutional assembly at Eidsvoll in Norway, that adopted the Norwegian Constitution and formalised the dissolution of the union with Denmark. In Norway, it is often just referred to as Eidsvollsforsamlingen, which means The Assembly of Eidsvoll.

The legal aspects of ritual slaughter include the regulation of slaughterhouses, butchers, and religious personnel involved with traditional shechita (Jewish) and dhabiha (Islamic). Regulations also may extend to butchery products sold in accordance with kashrut and halal religious law. Governments regulate ritual slaughter, primarily through legislation and administrative law. In addition, compliance with oversight of ritual slaughter is monitored by governmental agencies and, on occasion, contested in litigation.

Masud Gharahkhani is a Norwegian politician who has been serving as the President of the Storting since 2021, and as a Member of the Storting for Buskerud since 2017 for the Labour Party.

The expulsion of Catholics from Norway, from 1613 onwards, was a precaution taken against the Counter-Reformation movement, which was orchestrated by the Kings of Denmark–Norway, but after 1814 it was orchestrated by the Norwegian government.

The Succession to the Crown Act 2013 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that altered the laws of succession to the British throne in accordance with the 2011 Perth Agreement. The Act replaced male-preference primogeniture with absolute primogeniture for those in the line of succession born after 28 October 2011, which means the eldest child, regardless of gender, precedes any siblings. The Act also repealed the Royal Marriages Act 1772, ended disqualification of a person who married a Roman Catholic from succession, and removed the requirement for those outside the first six persons in line to the throne to seek the Sovereign's approval to marry. It came into force on 26 March 2015, at the same time as the other Commonwealth realms implemented the Perth Agreement in their own laws.

The Jew clause is in the vernacular name of the second paragraph of the Constitution of Norway from 1814 to 1851 and from 1942 to 1945. The clause, in its original form, banned Jews from entering Norway, and also forbade Jesuits and monastic orders. An exception was made for so-called Portuguese Jews. The penultimate sentence of the same paragraph is known as the Jesuit clause.

While the constitution of Norway establishes that the King of Norway must be Evangelical Lutheran, it also establishes that all individuals have the right to exercise their religion. The government's policies generally support the free practice of religion in the country, and it provides funding to religious organizations and anti-discrimination programs on a regular basis. According to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the Norwegian police, religiously motivated hate speech is prevalent, particularly online, and primarily targeting the Muslim and Jewish communities.

The Conventicle Act was a decree issued 13 January 1741 by King Christian VI of Denmark and Norway and forbade lay preachers from holding religious services – conventicles – without the approval of the local Lutheran priest. The law was repealed in 1839 in Denmark and 1842 in Norway, which lay the groundwork for freedom of assembly.

The Dissenter Act is a Norwegian law from 1845 that allowed Christian denominations other than the Church of Norway to establish themselves in the country. It was enacted on 16 July 1845, and remained in effect until it was replaced by the Act Relating to Religious Communities, etc. in 1969.

Olav Valen-Sendstad was a Norwegian theologian, priest, and philosopher.