The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is a U.S. federal government agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation which regulates civil aviation in the United States and surrounding international waters. Its powers include air traffic control, certification of personnel and aircraft, setting standards for airports, and protection of U.S. assets during the launch or re-entry of commercial space vehicles, powers over neighboring international waters were delegated to the FAA by authority of the International Civil Aviation Organization.

Charleston International Airport is a joint civil-military airport located in North Charleston, South Carolina, United States. The airport is operated by the Charleston County Aviation Authority under a joint-use agreement with Joint Base Charleston. It is South Carolina's busiest airport; in 2023 the airport served over 6.1 million passengers in its busiest year on record. The airport is located in North Charleston and is approximately 12 miles (19 km) northwest of downtown Charleston. The airport serves as a focus city for Breeze Airways. It is also home to the Boeing facility that assembles the 787 Dreamliner.

The Boeing 787 Dreamliner is an American wide-body airliner developed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes. After dropping its unconventional Sonic Cruiser project, Boeing announced the conventional 7E7 on January 29, 2003, which focused largely on efficiency. The program was launched on April 26, 2004, with an order for 50 aircraft from All Nippon Airways (ANA), targeting a 2008 introduction. On July 8, 2007, a prototype 787 without major operating systems was rolled out; subsequently the aircraft experienced multiple delays, until its maiden flight on December 15, 2009. Type certification was received in August 2011, and the first 787-8 was delivered in September 2011 before entering commercial service on October 26, 2011, with ANA.

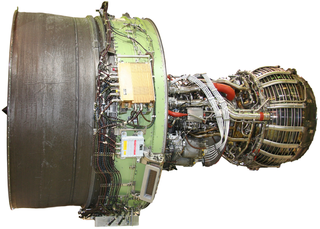

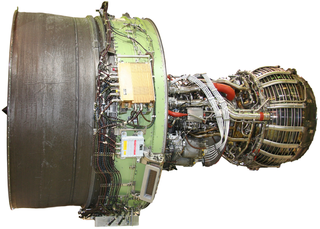

The General Electric GEnx is an advanced dual rotor, axial flow, high-bypass turbofan jet engine in production by GE Aerospace for the Boeing 747-8 and 787. The GEnx succeeded the CF6 in GE's product line.

SilkAir Flight 185 was a scheduled international passenger flight operated by a Boeing 737-300 from Soekarno–Hatta International Airport in Jakarta, Indonesia to Changi Airport in Singapore that crashed into the Musi River near Palembang, Sumatra, on 19 December 1997, killing all 97 passengers and seven crew on board.

The Boeing Company is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and product support services. Boeing is among the largest global aerospace manufacturers; it is the fourth-largest defense contractor in the world based on 2022 revenue and is the largest exporter in the United States by dollar value. Boeing was founded by William Boeing in Seattle, Washington, on July 15, 1916. The present corporation is the result of the merger of Boeing with McDonnell Douglas on August 1, 1997.

Southwest Airlines Flight 2294 (WN2294/SWA2294) was a scheduled US passenger aircraft flight which suffered a rapid depressurization of the passenger cabin on July 13, 2009. The aircraft made an emergency landing at Yeager Airport in Charleston, West Virginia, with no fatalities or major injuries to passengers and crew. An NTSB investigation found that the incident was caused by a failure in the fuselage skin due to metal fatigue.

Vincent A. Weldon is an American aerospace engineer who has designed critical components for both the Apollo Moon missions and the Space Shuttle. In 2006 Weldon called the Boeing 787 Dreamliner unsafe, and Boeing fired Weldon under disputed circumstances.

Boeing South Carolina is an airplane assembly facility built by Boeing in North Charleston, South Carolina, United States. Located on the grounds of the joint-use Charleston Air Force Base and Charleston International Airport, the site is the final assembly and delivery point for the Boeing 787 Dreamliner. Boeing opened the site in July 2011, after purchasing the facilities of suppliers Vought and Global Aeronautica in 2008 and 2009. The final assembly building covers 1,200,000 square feet (110,000 m2) and opened on November 12, 2011. As of September 28, 2017, the site employs 6,943 workers and contractors.

The Boeing 737 MAX is the fourth generation of the Boeing 737, a narrow-body airliner manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes, a division of American company Boeing. It succeeds the Boeing 737 Next Generation (NG) and competes with the Airbus A320neo family. The series was announced in August 2011, first flown in January 2016, and certified by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in March 2017. The first 737 MAX delivered to a customer was a MAX 8 to Malindo Air, which accepted and began operating the aircraft in May 2017.

In 2013, the second year of service for the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, a widebody jet airliner, several of the aircraft suffered from electrical system problems stemming from its lithium-ion batteries. Incidents included two electrical fires, one aboard an All Nippon Airways 787 and another on a Japan Airlines 787; the second fire was found by maintenance workers while the aircraft was parked at Boston's Logan International Airport. The United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) ordered a review of the design and manufacture of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and grounded the entire Boeing 787 fleet, the first such grounding since that of the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 in 1979. The plane has had two major battery thermal runaway events in 52,000 flight hours, neither of which were contained safely; this length of time between failures was substantially less than the 10 million flight hours predicted by Boeing.

The Boeing 737 MAX passenger airliner was grounded worldwide between March 2019 and December 2020 – longer in many jurisdictions – after 346 people died in two similar crashes in less than five months: Lion Air Flight 610 on October 29, 2018, and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on March 10, 2019. The Federal Aviation Administration initially affirmed the MAX's continued airworthiness, claiming to have insufficient evidence of accident similarities. By March 13, the FAA followed behind 51 concerned regulators in deciding to ground the aircraft. All 387 aircraft delivered to airlines were grounded by March 18.

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) is a flight stabilizing feature developed by Boeing that became notorious for its role in two fatal accidents of the 737 MAX in 2018 and 2019, which killed all 346 passengers and crew among both flights.

The Organization Designation Authorization (ODA) program was established by FAA Order 8100.15 . The ODA, in conjunction with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), grants airworthiness designee authority to organizations or companies. The regulations addressing the ODA program are found in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations part 183, subpart D, sections 183.41 through 813.67.

The two fatal Boeing 737 MAX crashes in October 2018 and March 2019 which were similar in nature – both aircraft were newly delivered and crashed shortly after takeoff – and the subsequent groundings of the global 737 MAX fleet drew mixed reactions from multiple organizations. Boeing expressed its sympathy to the relatives of the Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crash victims, while simultaneously defending the aircraft against any faults and suggesting the pilots had insufficient training, until rebutted by evidence. After the 737 MAX fleet was globally grounded, starting in China with the Civil Aviation Administration of China the day after the second crash, Boeing provided several outdated return-to-service timelines, the earliest of which was "in the coming weeks" after the second crash. On October 11, 2019, David L. Calhoun replaced Dennis Muilenburg as chairman of Boeing, then succeeded Muilenburg's role as chief executive officer in January 2020.

The Boeing 737 MAX was initially certified in 2017 by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Global regulators grounded the plane in 2019 following fatal crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. Both crashes were linked to the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), a new automatic flight control feature. Investigations into both crashes determined that Boeing and the FAA favored cost-saving solutions, which ultimately produced a flawed design of the MCAS instead. The FAA's Organization Designation Authorization program, allowing manufacturers to act on its behalf, was also questioned for weakening its oversight of Boeing.

Dominic Gates is an Irish-American aerospace journalist for The Seattle Times, former math teacher, and Pulitzer Prize winner. He has been assigned to cover Boeing for The Times since 2003. Gates was a co-recipient of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in National Reporting alongside Steve Miletich, Mike Baker, and Lewis Kamb for their coverage of the Boeing 737 MAX crashes and investigations.

Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 was a scheduled domestic flight operated by Alaska Airlines from Portland International Airport in Portland, Oregon, to Ontario International Airport in Ontario, California. Shortly after takeoff on January 5, 2024, a door plug on the Boeing 737 MAX 9 aircraft blew out, causing an uncontrolled decompression of the aircraft. The aircraft returned to Portland for an emergency landing. All 171 passengers and six crew members survived the accident, with three receiving minor injuries. An investigation of the accident by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is ongoing. A preliminary report published on February 6 said that four bolts, intended to secure the door plug, had been missing when the accident occurred and that Boeing records showed evidence that the plug had been reinstalled with no bolts prior to initial delivery of the aircraft.

On 11 March 2024, a LATAM Airlines Boeing 787-9 operating as LATAM Airlines Flight 800, flying a scheduled international passenger flight from Sydney, Australia to Santiago, Chile, with a stopover at Auckland, New Zealand, experienced an in-flight upset around two hours into the first leg of the flight. Of the 272 people onboard, 50 were injured, with 12 taken to the hospital after landing in Auckland.

A number of significant oversights have occurred in the manufacturing of aircraft produced by Boeing. Such oversights have been reported in the news as far back as 1987. Scrutiny over Boeing's process of addressing manufacturing issues began increasing in the aftermath of two fatal crashes involving the Boeing 737 MAX—Lion Air Flight 610 in late 2018 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in early 2019.