Legal trouble

He is reported to have made "many odious speeches in pulpit against the statesmen". [5] He was summoned before the Committee of Estates in Edinburgh on 13 October 1660, for preaching against the government and uttering speeches tending to division and sedition. He was immediately imprisoned and his congregation declared vacant. [6] He seems to have followed the example of Patrick Gillespie and recanted and petitioned the king for mercy. He was allowed his past year's stipend and to return to his charge following an order by Parliament on 19 April 1661. The Tolbooth record shows him released on 19 May 1661. [7] He was therefore allowed to return to Rutherglen around 1661. [8]

In May 1662 an act of parliament was passed which John Dickson could not comply with in good conscience and he therefore left his charge in Rutherglen. He was deprived by Act of Parliament on 11 June, and by Decree of Privy Council 1 October 1662.

He did not cease preaching but spoke in fields and on hillsides often at night for cover. He travelled east and is recorded preaching on several occasions in Fife. For example, he was present, along with Mr. John Blackadder, at the first armed conventicle held on the Hill of Beath, near Dunfermline, 16 June 1670. [9] "It was a great gathering of persons who came from the east of Fife and as far West as Stirling." For taking part in this service, Dickson and Blackadder were summoned to appear before the Privy Council on 11 August 1670 being charged with holding conventicles. But they both deemed it discreet not to show face. Dickson fled to London, while Blackadder sought a retreat in Edinburgh. Since he did not appear he was pronounced a rebel by being put to the horn. Dickson, however, did not remain long in London. Returning to Scotland, he resumed preaching in private houses or in the fields as he found most convenient. On 4 June 1674 a price of a 1000 merks was put on his head. Around 1676 he is recorded as preaching or assisting at services in Balvaird Castle, at Cassigour in Kinross, and near Tullibole church. [10] The covenanter also began to hold field communions at which they armed themselves for defense and Dickson is recorded as being at services at Nisbet and at Irongray.

After the defeat of the Covenanters at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge, Dickson gave up field preaching, which was a capital crime, and only held meetings in private houses.

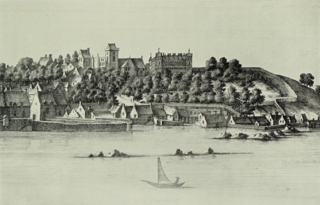

In 1680 Dickson was captured and tried in Edinburgh. "The Lords of his Majesty's Privy Council do hereby recommend to General Dalziel, lieutenant-general and commander-in-chief of his Majesty's forces, to cause immediately transport, by such a party of horse or foot as he shall think fit, the person of Mr John Dickson, prisoner, from the tolbooth of Edinburgh to the Isle of Bass, and ordain the Magistrates of Edinburgh to deliver the said prisoner to the said party, and the governor of the said isle to receive and detain him prisoner therein till further order."

He was imprisoned on the Bass Rock on the Firth of Forth in Haddingtonshire on 2 September 1680. [11] On 8 October 1686 orders were issued for a conditional release of prisoners on the Bass and at Blackness Castle. Dickson however would not meet their conditions and was sentenced to be sent back to the Bass. "Mr John Dickson, brought prisoner from the Bass, declares, that about six years ago he was taken for being present at conventicles; confesses he has kept conventicles several times; acknowledges the King's authority, but will not engage to live regularly and orderly, and not to keep conventicles; and shuns to give answer as to declaring the unlawfulness to rise in arms against the King or his authority: Ordered that the said Mr John Dickson and Mr Alexander Shields, brought prisoners from the Bass, be returned back prisoners thither until further order."

After sentence was passed Dickson made a petition that because of his age and ill health that he be allowed to stay in Edinburgh. This petition was granted on 13 October 1686: "allow the petitioner to stay in Edinburgh till the first council-day of November next, in regard of his valetudinary condition, he finding caution to appear before the Council that day, or to re-enter the tolbooth of Edinburgh the said day, under the penalty of 5000 merks."

After the Glorious Revolution he returned to his old parish in Rutherglen. [12] After officiating at Kelso, he was restored by Act of Parliament 25 April, and received on 6 October 1690. He died on 12 January 1700, aged about 71.