Qʼuqʼumatz was a deity of the Postclassic Kʼicheʼ Maya. Qʼuqʼumatz was the Feathered Serpent divinity of the Popol Vuh who created humanity together with the god Tepeu. Qʼuqʼumatz is considered to be the rough equivalent of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, and also of Kukulkan of the Yucatec Maya tradition. It is likely that the feathered serpent deity was borrowed from one of these two peoples and blended with other deities to provide the god Qʼuqʼumatz that the Kʼicheʼ worshipped. Qʼuqʼumatz may have had his origin in the Valley of Mexico; some scholars have equated the deity with the Aztec deity Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl, who was also a creator god. Qʼuqʼumatz may originally have been the same god as Tohil, the Kʼicheʼ sun god who also had attributes of the feathered serpent, but they later diverged and each deity came to have a separate priesthood.

In Maya mythology, Camazotz was a bat god. Camazotz means "death bat" in the Kʼicheʼ language. In Mesoamerica the bat was associated with night, death, and sacrifice.

Popol Vuh is a cultural narrative that recounts the mythology and history of the Kʼicheʼ people who inhabit the Guatemalan Highlands northwest of present-day Guatemala City.

Tohil was a deity of the Kʼicheʼ Maya in the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerica.

The Mayan languages form a language family spoken in Mesoamerica and northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least 6 million Maya peoples, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more within its territory.

Tecun Uman was one of the last rulers of the K'iche' Maya people, in the Highlands of what is now Guatemala. According to the Kaqchikel annals, he was slain by Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado while waging battle against the Spanish and their allies on the approach to Quetzaltenango on 12 February 1524. Tecun Uman was declared Guatemala's official national hero on March 22, 1960 and is commemorated on February 20, the popular anniversary of his death. Tecun Uman has inspired a wide variety of activities ranging from the production of statues and poetry to the retelling of the legend in the form of folkloric dances to prayers. Despite this, Tecun Uman's existence is not well documented, and it has proven to be difficult to separate the man from the legend.

Qʼumarkaj, is an archaeological site in the southwest of the El Quiché department of Guatemala. Qʼumarkaj is also known as Utatlán, the Nahuatl translation of the city's name. The name comes from Kʼicheʼ Qʼumarkah "Place of old reeds".

The Kaqchikel are one of the indigenous Maya peoples of the midwestern highlands in Guatemala. The name was formerly spelled in various other ways, including Cakchiquel, Cakchiquel, Kakchiquel, Caqchikel, and Cachiquel.

The Spanish conquest of Guatemala was a protracted conflict during the Spanish colonization of the Americas, in which Spanish colonisers gradually incorporated the territory that became the modern country of Guatemala into the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain. Before the conquest, this territory contained a number of competing Mesoamerican kingdoms, the majority of which were Maya. Many conquistadors viewed the Maya as "infidels" who needed to be forcefully converted and pacified, disregarding the achievements of their civilization. The first contact between the Maya and European explorers came in the early 16th century when a Spanish ship sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo was wrecked on the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511. Several Spanish expeditions followed in 1517 and 1519, making landfall on various parts of the Yucatán coast. The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a prolonged affair; the Maya kingdoms resisted integration into the Spanish Empire with such tenacity that their defeat took almost two centuries.

The Annals of the Cakchiquels is a manuscript written in Kaqchikel by Francisco Hernández Arana Xajilá in 1571, and completed by his grandson, Francisco Rojas, in 1604. The manuscript — which describes the legends of the Kaqchikel nation and has historical and mythological components — is considered an important historical document on post-classic Maya civilization in the highlands of Guatemala.

Iximcheʼ is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonment in 1524. The architecture of the site included a number of pyramid-temples, palaces and two Mesoamerican ballcourts. Excavators uncovered the poorly preserved remains of painted murals on some of the buildings and ample evidence of human sacrifice. The ruins of Iximche were declared a Guatemalan National Monument in the 1960s. The site has a small museum displaying a number of pieces found there, including sculptures and ceramics. It is open daily.

Classical Kʼicheʼ was an ancestral form of the modern-day Kʼicheʼ language, which was spoken in the highland regions of Guatemala around the time of the 16th century Spanish conquest of Guatemala. Classical Quiché has been preserved in a number of historical Mesoamerican documents, lineage histories, missionary texts and dictionaries, and is the language in which the renowned highland Maya creation account Popol Vuh is written.

The Museo Popol Vuh is home to one of the major collections of Maya art in the world. It is located on the campus of the Universidad Francisco Marroquín in Zone 10, Guatemala City and is known for its extensive collection of pre-Columbian and colonial art of the Maya culture.

The Kʼicheʼ kingdom of Qʼumarkaj was a state in the highlands of modern-day Guatemala which was founded by the Kʼicheʼ (Quiché) Maya in the thirteenth century, and which expanded through the fifteenth century until it was conquered by Spanish and Nahua forces led by Pedro de Alvarado in 1524.

The Baile de la Conquista or Dance of the Conquest is a traditional folkloric dance from Guatemala. The dance reenacts the invasion led by Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado and his confrontation with Tecun Uman, ruler of K'iche' kingdom of Q'umarkaj. Although the dance is more closely associated with Guatemalan traditions, it has been performed in early colonial regions of Latin America at the urging of Catholic friars and priests, as a method of converting various native populations and African slaves to the Catholic Church.

The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a protracted conflict during the Spanish colonisation of the Americas, in which the Spanish conquistadores and their allies gradually incorporated the territory of the Late Postclassic Maya states and polities into the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain. The Maya occupied a territory that is now incorporated into the modern countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador; the conquest began in the early 16th century and is generally considered to have ended in 1697.

Kʼicheʼ, or Quiché, is a Maya language of Guatemala, spoken by the Kʼicheʼ people of the central highlands. With over a million speakers, Kʼicheʼ is the second-most widely spoken language in the country after Spanish. Most speakers of Kʼicheʼ languages also have at least a working knowledge of Spanish.

The Spanish conquest of the Kingdom of Q'umarkaj took place in the K'iche' Kingdom of Q'umarkaj in 1524 between the Spanish and K'iche'. In 1524, conquistador Pedro de Alvarado arrived in Guatemala with 135 horsemen, 120 footsoldiers and 400 Aztec, Tlaxcaltec and Cholultec allies, and were offered help by the Kaqchikels. Tecun Uman prepared 8,400 soldiers for the Spanish attack, which they had discovered because of their network of spies. After several defeats over the K'iche' people, the Spanish entered Q'umarkaj and the Lords of Q'umarkaj were burnt alive by Alvarado. Following the war, two Spanish noblemen were put in charge of Q'umarkaj, although some fighting continued until 1527.

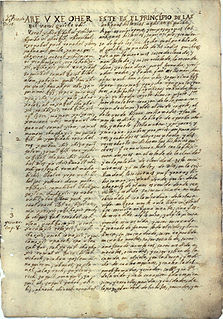

The Título de Totonicapán, sometimes referred to as the Título de los Señores de Totonicapán is the name given to a Kʼicheʼ language document written around 1554 in Guatemala. The Título de Totonicapán is one of the two most important surviving colonial period Kʼicheʼ language documents, together with the Popol Vuh. The document contains history and legend of the Kʼicheʼ people from their mythical origins down to the reign of their most powerful king, Kʼiqʼab.

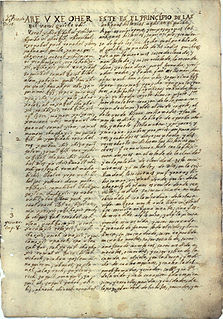

The Título Cʼoyoi is an important early colonial Kʼiche document documenting the mythical origins of the Kʼicheʼ people and their history up to the Spanish conquest. It describes Kʼicheʼ preparations for battle against the Spanish, and the death of the Kʼicheʼ hero Tecun Uman. The document was written in Qʼumarkaj, the Kʼicheʼ capital city, by the Cʼoyoi Sakcorowach lineage, which belonged to the Quejnay branch of the Kʼicheʼ, and who held territory just to the east of Quetzaltenango, now in Guatemala. The document was largely written by Juan de Penonias de Putanza, who claimed to be the relative of a Cʼoyoi nobleman who was killed during the Spanish conquest. It was composed with the assistance of the Kʼicheʼ officialdom at Qʼumarkaj, and portions of the text reflect the official version of Kʼicheʼ history as produced in the capital. An illustration in the document shows that the Maya nobility of Quetzaltenango adopted the double-headed Hapsburg Eagle as their family crest.