Vajrayāna, also known as Mantrayāna, Mantranāya, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, is a Buddhist tradition of tantric practice that developed in Medieval India and spread to Tibet, Nepal, other Himalayan states, East Asia, parts of Southeast Asia and Mongolia.

The Vajra is a legendary and ritualistic tool, symbolizing the properties of a diamond (indestructibility) and a thunderbolt. In Hinduism, it has also been associated with weapons.

Buddhist symbolism is the use of symbols to represent certain aspects of the Buddha's Dharma (teaching). Early Buddhist symbols which remain important today include the Dharma wheel, the Indian lotus, the three jewels and the Bodhi tree.

In Buddhism, wrathful deities or fierce deities are the fierce, wrathful or forceful forms of enlightened Buddhas, Bodhisattvas or Devas ; normally the same figure has other, peaceful, aspects as well. Because of their power to destroy the obstacles to enlightenment, they are also termed krodha-vighnantaka, "Wrathful onlookers on destroying obstacles". Wrathful deities are a notable feature of the iconography of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, especially in Tibetan art. These types of deities first appeared in India during the late 6th century, with its main source being the Yaksha imagery, and became a central feature of Indian Tantric Buddhism by the late 10th or early 11th century.

A yidam or iṣṭadevatā is a meditational deity that serves as a focus for meditation and spiritual practice, said to be manifestations of Buddhahood or enlightened mind. Yidams are an integral part of Vajrayana, including both Tibetan Buddhism and Shingon, which emphasize the use of esoteric practices and rituals to attain enlightenment more swiftly. The yidam is one of the three roots of the inner refuge formula and is also the key element of deity yoga. Yidam is sometimes translated by the term "tutelary deity".

A ḍākinī is a type of goddess in Hinduism and Buddhism.

A vajrācārya is a Vajrayana Buddhist master, guru or priest. It is a general term for a tantric master in Vajrayana Buddhist traditions, including Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Bhutanese Buddhism, Newar Buddhism.

Vajradhara is the ultimate primordial Buddha, or Adi-Buddha, according to the Sakya, Gelug and Kagyu schools of Tibetan Buddhism. It is also a name of Indra, because "Vajra" means diamond, as well as the thunderbolt, or anything hard more generally.

Chöd is a spiritual practice found primarily in the Yundrung Bön tradition as well as in the Nyingma and Kagyu schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Also known as "cutting through the ego," the practices are based on the Prajñāpāramitā or "Perfection of Wisdom" sutras, which expound the "emptiness" concept of Buddhist philosophy.

Vajrayoginī is an important figure in Buddhism, especially revered in Tibetan Buddhism. In Vajrayana she is considered a female Buddha and a ḍākiṇī. Vajrayoginī is often described with the epithet sarvabuddhaḍākiṇī, meaning "the ḍākiṇī [who is the Essence] of all Buddhas". She is an Anuttarayoga Tantra meditational deity (iṣṭadevatā) and her practice includes methods for preventing ordinary death, intermediate state (bardo) and rebirth (samsara) by transforming them into paths to enlightenment, and for transforming all mundane daily experiences into higher spiritual paths.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the Three Jewels and Three Roots are supports in which a Buddhist takes refuge by means of a prayer or recitation at the beginning of the day or of a practice session. The Three Jewels are the first and the Three Roots are the second set of three Tibetan Buddhist refuge formulations, the Outer, Inner and Secret forms of the Three Jewels. The 'Outer' form is the 'Triple Gem', the 'Inner' is the Three Roots and the 'Secret' form is the 'Three Bodies' or trikāya of a Buddha.

Nāroḍākinī is a deity in Vajrayana Buddhism similar to Vajrayogini who no longer appears in the active pantheon despite her importance in late Indian Buddhism.

A khaṭvāṅga is a long, studded staff or club originally understood as Shiva's weapon. It evolved as a traditional ritualistic symbol in Indian religions and Tantric traditions like Shaivism, and in the Vajrayana of Tibetan Buddhism. The khatvānga was also used as tribal shaman shafts.

A kapala is a skull cup used as a ritual implement (bowl) in both Hindu Tantra and Tibetan Buddhist Tantra (Vajrayana). Especially in Tibetan Buddhism, kapalas are often carved or elaborately mounted with precious metals and jewels.

In Tibetan Buddhism, Vajravārāhī is considered a female buddha and "the root of all emanations of dakinis". As such, Vajravarahi manifests in the colors of white, yellow, red, green, blue, and black. She is a popular deity in Tibetan Buddhism and in the Nyingma school she is the consort of Hayagriva, the wrathful form of Avalokiteshvara. She is also associated with the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra, where she is paired in yab-yum with the Heruka Cakrasaṃvara.

A charnel ground is an above-ground site for the putrefaction of bodies, generally human, where formerly living tissue is left to decompose uncovered. Although it may have demarcated locations within it functionally identified as burial grounds, cemeteries and crematoria, it is distinct from these as well as from crypts or burial vaults.

The Vidhyeshvari Vajra Yogini Temple - also known as the Bijeśvarī Vajrayoginī, Bidjeshwori Bajra Jogini, Bijayaswar, Bidjeswori, or Visyasvari Temple - is a Newar Buddhist temple in the Kathmandu valley dedicated to the Vajrayāna Buddhist deity Vajrayoginī in her form as Akash Yogini. The temple stands on the west bank of the Bishnumati river next to the ancient religious site of the Ramadoli (Karnadip) cremation ground and is on the main path from Swayambhunath stupa to Kathmandu.

Mekhala "The Elder Severed-Headed Sister" and Kanakhala "The Younger Severed-Headed Sister") are two sisters who figure in the eighty-four mahasiddhas of Vajrayana Buddhism. Both are described as the disciples of another mahasiddha, Kanhapa (Krishnacharya). They are said to have severed their heads and offered them to their guru, and then danced headless. Their legend is closely associated with the Buddhist severed-headed goddess Chinnamunda.

Mundamala, also called kapalamala or rundamala, is a garland of severed Asura heads and/or skulls, in Hindu iconography and Tibetan Buddhist iconography. In Hinduism, the mundamala is a characteristic of fearsome aspects of the Hindu Divine Mother and the god Shiva; while in Buddhism, it is worn by wrathful deities of Tibetan Buddhism.

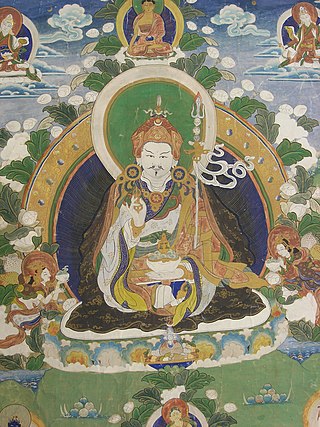

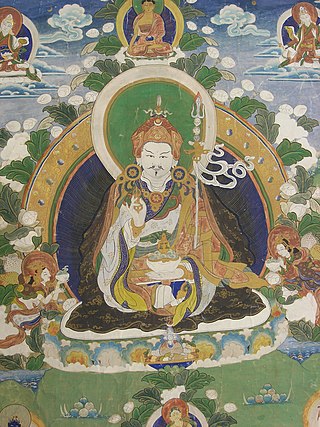

Tibetan Monasteries are known for their rich culture and traditions, which are rooted in the teachings of Buddhism. An important aspect of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries is the presence of ritualistic places that are dedicated to deities. Vajrayana Buddhism contains intricate iconography that deals with deities and religious practices. To a devotee, it may appear as images and icons to bring luck or drive away evil spirits. Thangkas at monasteries show Buddha, Gurus, Yantras, andMandalas, which bring good luck, health, prosperity, wisdom, longevity, and peace.