Omaha is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about 10 mi (15 km) north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 40th-most populous city, Omaha had a population of 486,051 as of the 2020 census. It is the anchor of the eight-county Omaha–Council Bluffs metropolitan area, which extends into Iowa and is the 58th-largest metro area in the United States, with a population of 967,604. Furthermore, the greater Omaha–Council Bluffs–Fremont combined statistical area had 1,004,771 residents in 2020.

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the east, as defined by the University of Nebraska at Omaha and the Omaha Chamber of Commerce.

North Omaha, Nebraska has a recorded history spanning over 200 years, pre-dating the rest of Omaha, encompassing wildcat banks, ethnic enclaves, race riots and social change. North Omaha has roots back to 1812 and the founding of Fort Lisa. It includes the Mormon settlement of Cutler's Park and Winter Quarters in 1846, a lynching before the turn of the twentieth century, the thriving 24th Street community of the 1920s, the bustling development of its African-American community through the 1950s, a series of riots in the 1960s, and redevelopment in the late 20th and early 21st century.

Significant events in the history of North Omaha, Nebraska include the Pawnee, Otoe and Sioux nations; the African American community; Irish, Czech, and other European immigrants, and; several other populations. Several important settlements and towns were built in the area, as well as important social events that shaped the future of Omaha and the history of the nation. The timeline of North Omaha history extends to present, including recent controversy over schools.

Saratoga Springs, Nebraska Territory, or Saratoga, was a boom and bust town founded in 1856 that thrived for several years. During its short period of influence the town grew quickly, outpacing other local settlements in the area including Omaha and Florence, and briefly considered as a candidate for the Nebraska Territorial capitol. Saratoga was annexed into Omaha in 1887, and has been regarded a neighborhood in North Omaha since then.

The history of Omaha, Nebraska, began before the settlement of the city, with speculators from neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa staking land across the Missouri River illegally as early as the 1840s. When it was legal to claim land in Indian Country, William D. Brown was operating the Lone Tree Ferry to bring settlers from Council Bluffs to Omaha. A treaty with the Omaha Tribe allowed the creation of the Nebraska Territory, and Omaha City was founded on July 4, 1854. With early settlement came claim jumpers and squatters, and the formation of a vigilante law group called the Omaha Claim Club, which was one of many claim clubs across the Midwest. During this period many of the city's founding fathers received lots in Scriptown, which was made possible by the actions of the Omaha Claim Club. The club's violent actions were challenged successfully in a case ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, Baker v. Morton, which led to the end of the organization.

The neighborhoods of Omaha are a diverse collection of community areas and specific enclaves. They are spread throughout the Omaha metro area, and are all on the Nebraska side of the Missouri River.

Culture in North Omaha, Nebraska, the north end of Omaha, is defined by socioeconomic, racial, ethnic and political diversity among its residents. The neighborhood's culture is largely influenced by its predominantly African American community.

The DePorres Club was an early pioneer organization in the Civil Rights Movement in Omaha, Nebraska, whose "goals and tactics foreshadowed the efforts of civil rights activists throughout the nation in the 1960s." The club was an affiliate of CORE.

Racial tension in Omaha, Nebraska occurred mostly because of the city's volatile mixture of high numbers of new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and African-American migrants from the Deep South. While racial discrimination existed at several levels, the violent outbreaks were within working classes. Irish Americans, the largest and earliest immigrant group in the 19th century, established the first neighborhoods in South Omaha. All were attracted by new industrial jobs, and most were from rural areas. There was competition among ethnic Irish, newer European immigrants, and African-American migrants from the South, for industrial jobs and housing. They all had difficulty adjusting to industrial demands, which were unmitigated by organized labor in the early years. Some of the early labor organizing resulted in increasing tensions between groups, as later arrivals to the city were used as strikebreakers. In Omaha as in other major cities, racial tension has erupted at times of social and economic strife, often taking the form of mob violence as different groups tried to assert power. Much of the early violence came out of labor struggles in early 20th century industries: between working class ethnic whites and immigrants, and blacks of the Great Migration. Meatpacking companies had used the latter for strikebreakers in 1917 as workers were trying to organize. As veterans returned from World War I, both groups competed for jobs. By the late 1930s, however, interracial teams worked together to organize the meatpacking industry under the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA). Unlike the AFL and some other industrial unions in the CIO, UPWA was progressive. It used its power to help end segregation in restaurants and stores in Omaha, and supported the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Women labor organizers such as Tillie Olsen and Rowena Moore were active in the meatpacking industry in the 1930s and 1940s, respectively.

Rowena Moore was an African-American union and civic activist, and founder of the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation in Omaha, Nebraska. She led the effort to have the Malcolm X House Site recognized for its association with the life of the national civil-rights leader. It was listed on both the National Register of Historic Places and the Nebraska register of historic sites.

The Near North Side of Omaha, Nebraska is the neighborhood immediately north of downtown. It forms the nucleus of the city's historic African-American community, and its name is often synonymous with the entire North Omaha area. Originally established immediately after Omaha was founded in 1854, the Near North Side was once confined to the area around Dodge Street and North 7th Street. Eventually, it gravitated west and north, and today it is bordered by Cuming Street on the south, 30th on the west, 16th on the east, and Locust Street to the north. Countless momentous events in Omaha's African American community happened in the Near North Side, including the 1865 establishment of the first Black church in Omaha, St. John's AME; the 1892 election of the first African American state legislator, Dr. Matthew Ricketts; the 1897 hiring of the first Black teacher in Omaha, Ms. Lucy Gamble, the 1910 Jack Johnson riots, the Omaha race riot of 1919 that almost demolished the neighborhood and many other events.

The Black Association for Nationalism Through Unity, or BANTU, was a youth activism group focused on black power and nationalism in Omaha, Nebraska in the 1960s. Its name is a reference to the Bantu peoples of Southern Africa.

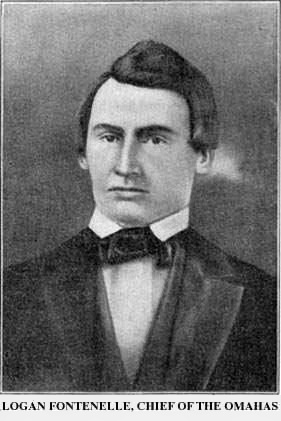

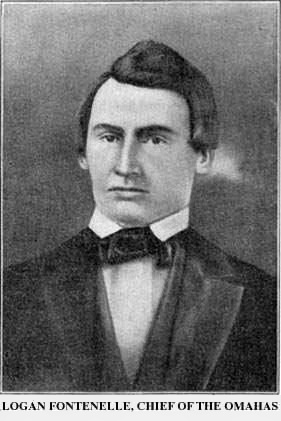

Logan Fontenelle, also known as Shon-ga-ska, was a trader of Omaha and French ancestry, who served for years as an interpreter to the US Indian agent at the Bellevue Agency in Nebraska. He was especially important during the United States negotiations with Omaha leaders in 1853–1854 about ceding land to the United States prior to settlement on a reservation. His mother was a daughter of Big Elk, the principal chief, and his father was a respected French-American fur trader.

The Livestock Exchange Building in Omaha, Nebraska, was built in 1926 at 4920 South 30 Street in South Omaha. It was designed as the centerpiece of the Union Stockyards by architect George Prinz and built by Peter Kiewit and Sons in the Romanesque revival and Northern Italian Renaissance Revival styles. In 1999 it was designated an Omaha Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Union Stockyards were closed in 1999, and the Livestock Exchange Building underwent an extensive renovation over the next several years.

African Americans in Omaha, Nebraska, are central to the development and growth of the 43rd largest city in the United States. While population statistics show almost constantly increasing percentages of Black people living in the city since it was founded in 1854, Black people in Omaha have not been represented equitably in the city's political, social, cultural, economic or educational circumstances since. In the 2020s, the city's African American population is transforming the city's landscape through community investment, leadership and other initiatives.

Omaha Housing Authority,, is the government agency responsible for providing public housing in Omaha, Nebraska. It is the parent organization of Housing in Omaha, Inc., a nonprofit housing developer for low-income housing.

Various ethnic groups in Omaha, Nebraska have lived in the city since its organization by Anglo-Americans in 1854. Native Americans of various nations lived in the Omaha territory for centuries before European arrival, and some stayed in the area. The city was founded by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants from neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa. However, since the first settlement, substantial immigration from all of Europe, migration by African Americans from the Deep South and various ethnic groups from the Eastern United States, and new waves of more recent immigrants from Mexico and Africa have added layers of complexity to the workforce, culture, religious and social fabric of the city.

North 24th Street is a two-way street that runs south–north in the North Omaha area of Omaha, Nebraska, United States. With the street beginning at Dodge Street, the historically significant section of the street runs from Cuming Street to Ames Avenue. A portion of North 24th near Lake Street is considered the "Main Street" of the Near North Side, and was historically referred to as "The Street of Dreams." The corridor is widely considered the heart of Omaha's African-American community.

Significant events in the history of Omaha, Nebraska, include social, political, cultural, and economic activities.