King Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. The kings who were in times past, had this desire, that men might (be made to) progress by the promotion of morality; but men were not made to progress by an adequate promotion of morality.

Concerning this, King Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. The following occurred to me. On one hand, in times past kings had this desire, that men might (be made to) progress by an adequate promotion of morality; (but) on the other hand, men were not made to progress by an adequate promotion of morality. How then might men (be made to) conform to (morality)? How might men (be made to) progress by an adequate promotion of morality? How could I elevate them by the promotion of morality?

Concerning this, King Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. The following occurred to me. I shall issue proclamations on morality, (and) shall order instruction in morality (to be given). Hearing this, men will conform to (it), will be elevated, and will (be made to) progress considerably by the promotion of morality. For this purpose proclamations on morality were issued by me, (and) manifold instruction in morality was ordered (to be given), [in order that those agents] (of mine) too, who are occupied with many people, will exhort (them) and will explain (morality to them) in detail. The Lajukas also, who are occupied with many hundred thousands of men, —these too were ordered by me: "In such and such a manner exhort ye the people who are devoted to morality".

Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. Having in view this very (matter), I have set up pillars of morality (Dhaṃma taṃbhāni, ie "pillars of the Dharma"), appointed Mahamatras of morality (Dhaṃma Mahāmātā, the "Inspectors of the Dharma"), (and) issued [proclamations] on morality.

King Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. On the roads banyan-trees were caused to be planted by me, (in order that) they might afford shade to cattle and men, (and) mango-groves were caused to be planted. And (at intervals) of eight kos wells were caused to be dug by me, and flights of steps (for descending into the water) were caused to be built. Numerous drinking-places were caused to be established by me, here and there, for the enjoyment of cattle and men. [But] this so-called enjoyment (is) [of little consequence]. For with various comforts have the people been blessed both by former kings and by myself. But by me this has been done for the following purpose: that they might conform to that practice of morality.

Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. Those my Mahamatras of morality too are occupied with affairs of many kinds which are beneficial to ascetics as well as to householders, and they are occupied also with all sects. Some (Mahamatras) were ordered by me to busy themselves with the affairs of the Sangha; likewise others were ordered by me to busy themselves also with the Brahmanas (and) Ajivikas; others were ordered by me to busy themselves also with the Nirgranthas; others were ordered by me to busy themselves also with various (other) sects; (thus) different Mahamatras (are busying themselves) specially with different (congregations). But my Mahamatras of morality are occupied with these (congregations) as well as with all other sects.

King Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. Both these and many other chief (officers) are occupied with the delivery of the gifts of myself as well as of the queens, and among my whole harem [they are reporting] in divers ways different worthy recipients of charity both here and in the provinces. And others were ordered by me to busy themselves also with the delivery of the gifts of (my) sons and of other queens' sons, in order (to promote) noble deeds of morality (and) the practice of morality. For noble deeds of morality and the practice of morality (consist in) this, that (morality), viz. compassion, liberality, truthfulness, purity, gentleness, and goodness, will thus be promoted among men.

King Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. Whatsoever good deeds have been performed by me, those the people have imitated, and to those they are conforming. Thereby they have been made to progress and will (be made to) progress in obedience to mother and father, in obedience to elders, in courtesy to the aged, in courtesy to Brahmanas and Sramanas, to the poor and distressed, (and) even to slaves and servants.

King Beloved of the Gods Priyadarsin speaks thus. Now this progress of morality among men has been promoted (by me) only in two ways, (viz.) by moral restrictions and by conversion. But among these (two), those moral restrictions are of little consequence; by conversion, however, (morality is promoted) more considerably. Now moral restrictions indeed are these, that I have ordered this, (that) certain animals are inviolable. But there are also many other moral restrictions which have been imposed by me. By conversion, however, the progress of morality among men has been promoted more considerably, (because it leads) to abstention from hurting living beings (and) to abstention from killing animals.

Now for the following purpose has this been ordered, that it may last as long as (my) sons and great-grandsons (shall reign and) as long as the moon and the sun (shall shine), and in order that (men) may conform to it. For if one conforms to this, (happiness) in this (world) and in the other (world) will be attained.

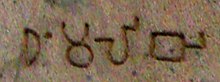

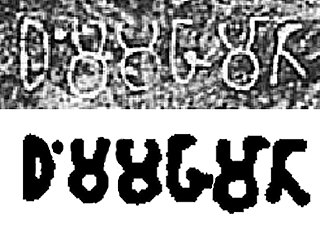

This rescript on morality was caused to be written by me (when I had been) anointed twenty-seven years.

Concerning this, Beloved of the Gods says. This rescript on morality must be engraved there, where either stone pillars or stone slabs are (available), in order that this may be of long duration.