The Santa Clara River is an 83 mi (134 km) long river in Ventura and Los Angeles counties in Southern California. It drains parts of four ranges in the Transverse Ranges System north and northwest of Los Angeles, then flows west onto the Oxnard Plain and into the Santa Barbara Channel of the Pacific Ocean.

The Elwha River is a 45-mile (72 km) river on the Olympic Peninsula in the U.S. state of Washington. From its source at Elwha snowfinger in the Olympic Mountains, it flows generally north to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Most of the river's course is within the Olympic National Park.

The Santa Ynez River is one of the largest rivers on the Central Coast of California. It is 92 miles (148 km) long, flowing from east to west through the Santa Ynez Valley, reaching the Pacific Ocean at Surf, near Vandenberg Space Force Base and the city of Lompoc.

Rindge Dam is a 100-foot-tall (30 m) dam on Malibu Creek in the Santa Monica Mountains of Southern California. Located in Malibu Creek State Park, it sits just northeast of Malibu Canyon Road, and is partially visible from the turnouts south of the tunnel. The dam, a major obstacle to river wildlife, is due to be removed with demolition work beginning in 2025 and finishing in 2035.

Malibu Creek is a year-round stream in western Los Angeles County, California. It drains the southern Conejo Valley and Simi Hills, flowing south through the Santa Monica Mountains, and enters Santa Monica Bay in Malibu. The Malibu Creek watershed drains 109 square miles (280 km2) and its tributary creeks reach as high as 3,000 feet (910 m) into Ventura County. The creek's mainstem begins south of Westlake Village at the confluence of Triunfo Creek and Lobo Canyon Creek, and flows 13.4 miles (21.6 km) to Malibu Lagoon.

The Carmel River is a 41 mi (66 km) river on the Central Coast of California in Monterey County that originates in the Ventana Wilderness of the Santa Lucia Mountains. The river flows northwest through Carmel Valley with its mouth at the Pacific Ocean south of Carmel-by-the-Sea, at Carmel Bay. The Carmel River is considered the northern boundary of Big Sur, the other boundaries being San Carpóforo Creek and the Pacific coastline.

The Sisquoc River is a westward flowing river in northeastern Santa Barbara County, California. It is a tributary of the Santa Maria River, which is formed when the Sisquoc River meets the Cuyama River at the Santa Barbara County and San Luis Obispo County border just north of Garey. The river is 57.4 miles (92.4 km) long and originates on the north slopes of Big Pine Mountain, at approximately 6,320 feet (1,930 m). Big Pine Mountain is part of the San Rafael Mountains, which are part of the Transverse Ranges.

The Ventura River, in western Ventura County in southern California, United States, flows 16.2 miles (26.1 km) from its headwaters to the Pacific Ocean. The smallest of the three major rivers in Ventura County, it flows through the steeply sloped, narrow Ventura Valley, with its final 0.7 miles (1.1 km) through the broader Ventura River estuary, which extends from where it crosses under a 101 Freeway bridge through to the Pacific Ocean.

Alameda Creek is a large perennial stream in the San Francisco Bay Area. The creek runs for 45 miles (72 km) from a lake northeast of Packard Ridge to the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay by way of Niles Canyon and a flood control channel. Along its course, Alameda Creek provides wildlife habitat, water supply, a conduit for flood waters, opportunities for recreation, and a host of aesthetic and environmental values. The creek and three major reservoirs in the watershed are used as water supply by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, Alameda County Water District and Zone 7 Water Agency. Within the watershed can be found some of the highest peaks and tallest waterfall in the East Bay, over a dozen regional parks, and notable natural landmarks such as the cascades at Little Yosemite and the wildflower-strewn grasslands and oak savannahs of the Sunol Regional Wilderness.

The Elwha Dam was a 108-ft high dam located in the United States, in the state of Washington, on the Elwha River approximately 4.9 miles (7.9 km) upstream from the mouth of the river on the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

San Francisquito Creek is a creek that flows into southwest San Francisco Bay in California, United States. Historically it was called the Arroyo de San Francisco by Juan Bautista de Anza in 1776. San Francisquito Creek courses through the towns of Portola Valley and Woodside, as well as the cities of Menlo Park, Palo Alto, and East Palo Alto. The creek and its Los Trancos Creek tributary define the boundary between San Mateo and Santa Clara counties.

Matilija Creek is a major stream in Ventura County in the U.S. state of California. It joins with North Fork Matilija Creek to form the Ventura River. Many tributaries feed the mostly free flowing, 17.3-mile (27.8 km) creek, which is largely contained in the Matilija Wilderness. Matilija was one of the Chumash rancherias under the jurisdiction of Mission San Buenaventura. The meaning of the Chumash name is unknown.

Dam removal is the process of demolishing a dam, returning water flow to the river. Arguments for dam removal consider whether their negative effects outweigh their benefits. The benefits of dams include hydropower production, flood control, irrigation, and navigation. Negative effects of dams include environmental degradation, such as reduced primary productivity, loss of biodiversity, and declines in native species; some negative effects worsen as dams age, like structural weakness, reduced safety, sediment accumulation, and high maintenance expense. The rate of dam removals in the United States has increased over time, in part driven by dam age. As of 1996, 5,000 large dams around the world were more than 50 years old. In 2020, 85% percent of dams in the United States are more than 50 years old. In the United States roughly 900 dams were removed between 1990 and 2015, and by 2015, the rate was 50 to 60 per year. France and Canada have also completed significant removal projects. Japan's first removal, of the Arase Dam on the Kuma River, began in 2012 and was completed in 2017. A number of major dam removal projects have been motivated by environmental goals, particularly restoration of river habitat, native fish, and unique geomorphological features. For example, fish restoration motivated the Elwha Ecosystem Restoration and the dam removal on the river Allier, while recovery of both native fish and of travertine deposition motivated the restoration of Fossil Creek.

The Elwha Ecosystem Restoration Project is a 21st-century project of the U.S. National Park Service to remove two dams on the Elwha River on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state, and restore the river to a natural state. It is the largest dam removal project in history and the second largest ecosystem restoration project in the history of the National Park Service, after the Restoration of the Everglades. The controversial project, costing about $351.4 million, has been contested and periodically blocked for decades. It has been supported by a major collaboration among the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, and federal and state agencies.

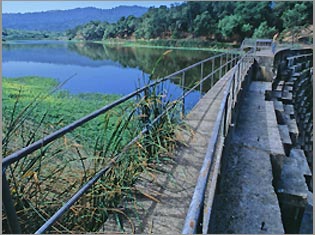

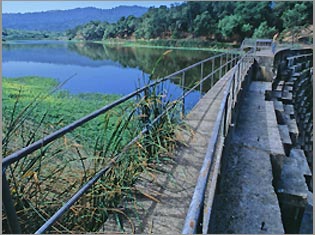

Searsville Dam is a masonry dam in San Mateo County, California, that was completed in 1892, one year after the founding of Stanford University, and impounds Corte Madera Creek to form a reservoir known as Searsville Reservoir or Searsville Lake. Searsville Dam is located in the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve and is owned and operated by Stanford University. Neighboring cities include Woodside and Portola Valley, California.

Gibraltar Dam is located on the Santa Ynez River, in southeastern Santa Barbara County, California, in the United States. Forming Gibraltar Reservoir, the dam is owned by the city of Santa Barbara. Originally constructed in 1920 and expanded in 1948, the dam and reservoir are located in a remote part of the Los Padres National Forest.

The Salt River is a formerly navigable hanging channel of the Eel River which flowed about 9 miles (14 km) from near Fortuna and Waddington, California, to the estuary at the Pacific Ocean, until siltation from logging and agricultural practices essentially closed the channel. It was historically an important navigation route until the early 20th century. It now intercepts and drains tributaries from the Wildcat Hills along the south side of the Eel River floodplain. Efforts to restore the river began in 1987, permits and construction began in 2012, and water first flowed in the restored channel in October 2013.

Guadalupe Creek is a 10.5 miles (16.9 km) northward-flowing stream originating just east of the peak of Mount Umunhum in Santa Clara County, California, United States. It courses along the northwestern border of Almaden Quicksilver County Park in the Cañada de los Capitancillos before joining Los Alamitos Creek after the latter exits Lake Almaden. This confluence forms the Guadalupe River mainstem, which in turn flows through San Jose and empties into south San Francisco Bay at Alviso Slough.

The Matilija Wilderness is a 29,207-acre (11,820 ha) wilderness area in Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, Southern California. It is managed by the U.S. Forest Service, being situated within the Ojai Ranger District of the Los Padres National Forest. It is located adjacent to the Dick Smith Wilderness to the northwest and the Sespe Wilderness to the northeast, although it is much smaller than either one. The Matilija Wilderness was established in 1992 in part to protect California condor habitat.