A tenant farmer is a person who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management, while tenant farmers contribute their labor along with at times varying amounts of capital and management. Depending on the contract, tenants can make payments to the owner either of a fixed portion of the product, in cash or in a combination. The rights the tenant has over the land, the form, and measures of payment vary across systems. In some systems, the tenant could be evicted at whim ; in others, the landowner and tenant sign a contract for a fixed number of years. In most developed countries today, at least some restrictions are placed on the rights of landlords to evict tenants under normal circumstances.

Abitibi-Ouest Regional County Municipality is a regional county municipality located in the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region of Quebec. Its seat is La Sarre.

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement in which a landowner allows a tenant (sharecropper) to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land. Sharecropping is not to be conflated with tenant farming, providing the tenant a higher economic and social status.

Gaspé is a city at the tip of the Gaspé Peninsula in the Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine region of eastern Quebec in Canada. Gaspé is about 650 km (400 mi) northeast of Quebec City and 350 km (220 mi) east of Rimouski. Gaspé has a total population of 15,063, as of the 2021 Canadian Census.

The ferme générale was, in ancien régime France, essentially an outsourced customs, excise and indirect tax operation. It collected duties on behalf of the King, under renewable six-year contracts. The major tax collectors in that highly unpopular tax farming system were known as the fermiers généraux, which would be tax farmers-general in English.

Francization or Francisation, also known as Frenchification, is the expansion of French language use—either through willful adoption or coercion—by more and more social groups who had not before used the language as a common means of expression in daily life. As a linguistic concept, known usually as gallicization, it is the practice of modifying foreign words, names, and phrases to make them easier to spell, pronounce, or understand in French.

Senneville is an affluent on-island suburban village on the western tip of the Island of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It is the wealthiest town in the West Island.

Sharefarming is an umbrella term for various systems of farming in which sharefarmers make use of agricultural assets they do not own in return for a percentage share of the profits, whether this be in currency or in kind.

A prendeur, a French term, is a labourer working as part of an early Middle Age sharecropping system known as complant, a precursor to the métayage system. Under this system, the prendeur would cultivate land owned by a bailleur. In exchange for using the bailleur's soil, the prendeur promised a share of the crop or its revenue. The length of this partnership varied and sometimes would extend over generations.

A bailleur, a French term, is a landowner who outsourced uncultivated parcels of land as part of an early Middle Age sharecropping system known as complant — a precursor to the métayage system. Under this system, a laborer known as a prendeur would agree to cultivate land owned by the bailleur in exchange for ownership of the crop and its production. For use of the bailleur's soil, the prendeur promised a share of the crop's production or its revenue to the bailleur. The length of this partnership varied, and would sometimes extend over generations.

Olivier de Serres was a French author and soil scientist whose Théâtre d'Agriculture (1600) was the accepted textbook of French agriculture in the 17th century.

Plessisville, Quebec is a county seat of L'Érable Regional County Municipality, Quebec, Canada. Routes 116 and 165 go through it. The city is 185 km from Montreal and 95 km from Quebec City. The city has hosted an annual Maple festival since 1958, and the Institut québécois de l'érable is headquartered there. The production of maple syrup and maple products is a major industry in the entire area, even giving the regional county municipality its name.

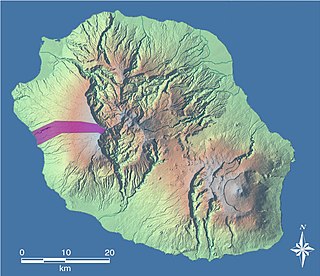

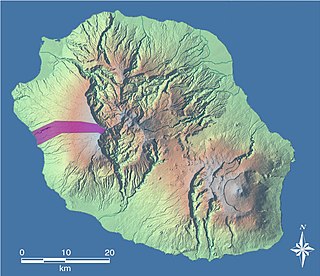

Du battant des lames au sommet des montagnes is a French expression that formerly served to define the geographic concessions accorded by the French East India Company to the colonists of the island of Réunion when it was still called île Bourbon. Since then, the expression has become a common phrase, indeed a "fixed formula". In its strictest meaning, it acts grammatically as an answer to the question "how?" and explains the way in which the land was cut into straight bands that stretch from the shore to the highest points without ever stretching horizontally. On the other hand, considered in its broader meaning, the expression substitutes for an adverb of place, being a synonym for "everywhere".

Crop share rent is a proportion of the crop harvest (yield) to be paid by the tenant farmer to the land owner as compensation for occupying and exploiting the rented land.

Ferme-Neuve is a municipality part of the Antoine-Labelle Regional County Municipality, in the Laurentides region of Quebec, Canada. It is the largest incorporated municipality of the Laurentides region.

André Desrochers is a Quebec scientist with expertise in ornithology and ecology.

Forest growth models are mathematical or computer models to project the future state and yields of forest stands or forest trees, over a time scale of from a few years to many decades.

Loud is the stage name of Simon Cliche Trudeau, a Canadian rapper from Quebec.

Québec Cinéma presents an annual award for Best Director to recognize the best in the Cinema of Quebec.

The Prix Iris for Best Screenplay is an annual film award, presented by Québec Cinéma as part of its Prix Iris program, to honour the year's best screenplay in the Cinema of Quebec.