Ambrose Powell Hill Jr. was a Confederate general who was killed in the American Civil War. He is usually referred to as A. P. Hill to differentiate him from Confederate general Daniel Harvey Hill, who was unrelated.

Cataraqui Cemetery is a non-denominational cemetery located in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Founded in 1850, it predates Canadian Confederation, and continues as an active burial ground. The cemetery is 91 acres in a rural setting with rolling wooded terrain, ponds and watercourses. More than 46,000 individuals are interred within the grounds, and it is the final resting place of many prominent Canadians, including the burial site of Canada's first prime minister, John A. Macdonald. The Macdonald family gravesite, and the cemetery itself, are both designated as National Historic Sites of Canada.

Oakland Cemetery is one of the largest cemetery green spaces in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded as Atlanta Cemetery in 1850 on six acres (2.4 hectares) of land southeast of the city, it was renamed in 1872 to reflect the large number of oak and magnolia trees growing in the area. By that time, the city had grown and the cemetery had enlarged correspondingly to the current 48 acres (190,000 m2). Since then, Atlanta has continued to expand so that the cemetery is now located in the center of the city. Oakland is an excellent example of a Victorian-style cemetery, and reflects the "garden cemetery" movement started and exemplified by Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts.

Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery is a federal military cemetery in the city of San Diego, California. It is located on the grounds of the former Army coastal artillery station Fort Rosecrans and is administered by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. The cemetery is located approximately 10 miles (16 km) west of Downtown San Diego, overlooking San Diego Bay and the city from one side, and the Pacific Ocean on the other. Fort Rosecrans is named after William Starke Rosecrans, a Union general in the American Civil War. The cemetery was registered as California Historical Landmark #55 on December 6, 1932. The cemetery is spread out over 77.5 acres (31.4 ha) located on both sides of Catalina Blvd.

Glenwood Cemetery is located in Houston, Texas, United States. Developed in 1871, the first professionally designed cemetery in the city accepted its first burial in 1872. Its location at Washington Avenue overlooking Buffalo Bayou served as an entertainment attraction in the 1880s. The design was based on principles for garden cemeteries, breaking the pattern of the typical gridiron layouts of most Houston cemeteries. Many influential people lay to rest at Glenwood, making it the "River Oaks of the dead." As of 2018, Glenwood includes the annexed property of the adjacent Washington Cemetery, creating a total area of 84 acres (34 ha) with 18 acres (7.3 ha) still undeveloped.

Pompeo Luigi Coppini was an Italian born sculptor who emigrated to the United States. Although his works can be found in Italy, Mexico and a number of U.S. states, the majority of his work can be found in Texas. He is particularly famous for the Alamo Plaza work, Spirit of Sacrifice, a.k.a. The Alamo Cenotaph, as well as numerous statues honoring Texan figures, such as Lawrence Sullivan Ross, the fourth President of Texas A&M University.

The Texas State Cemetery (TSC) is a cemetery located on about 22 acres (8.9 ha) just east of downtown Austin, the capital of the U.S. state of Texas. Originally the burial place of Edward Burleson, Texas Revolutionary general and vice-president of the Republic of Texas, it was expanded into a Confederate cemetery during the Civil War. Later it was expanded again to include the graves and cenotaphs of prominent Texans and their spouses.

Laurel Hill Cemetery, also called Laurel Hill East to distinguish it from the affiliated West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, is a historic rural cemetery in the East Falls neighborhood of Philadelphia. Founded in 1836, it was the second major rural cemetery in the United States after Mount Auburn Cemetery in Boston, Massachusetts.

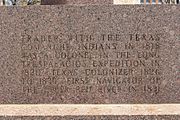

Henry Wax Karnes was notable as a soldier and figure of the Texas Revolution, as well as the commander of General Sam Houston's "Spy Squad" at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Benjamin Rush Milam was an American colonist of Mexican Texas and a military leader and hero of the Texas Revolution. A native of what is now Kentucky, Milam fought beside American interests during the Mexican War of Independence and later joined the Texians in their own fight for independence, for which he assumed a leadership role. Persuading the weary Texians not to back down during the Siege of Béxar, Milam was killed in action while leading an assault into the city that eventually resulted in the Mexican Army's surrender. Milam County, Texas and the town of Milam are named in his honor, as are many other placenames and civic works throughout Texas.

Oaklawn Cemetery is the first public burial ground in Tampa, Florida, United States. The location was deeded in the mid-19th century and was described as the final resting place for "White and Slave, Rich and Poor." Oaklawn Cemetery is located at the intersection of Morgan Street and Harrison Street in downtown Tampa, about two blocks South of I-275. It has approximately 1,700 graves.

Confederate monuments and memorials in the United States include public displays and symbols of the Confederate States of America (CSA), Confederate leaders, or Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War. Many monuments and memorials have been or will be removed under great controversy. Part of the commemoration of the American Civil War, these symbols include monuments and statues, flags, holidays and other observances, and the names of schools, roads, parks, bridges, buildings, counties, cities, lakes, dams, military bases, and other public structures. In a December 2018 special report, Smithsonian Magazine stated, "over the past ten years, taxpayers have directed at least $40 million to Confederate monuments—statues, homes, parks, museums, libraries, and cemeteries—and to Confederate heritage organizations."

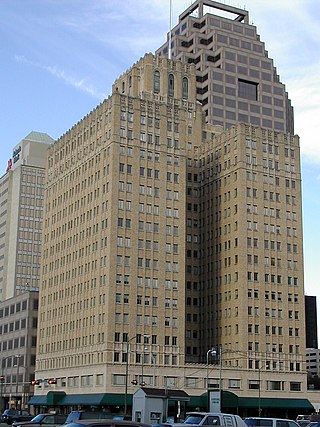

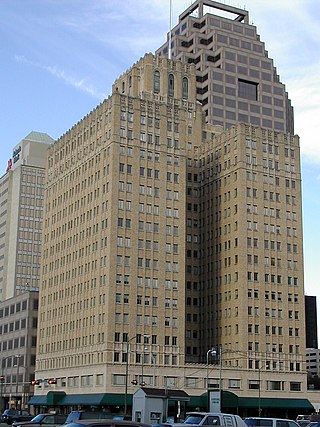

The Milam Building is a historic 21-story building in downtown San Antonio, Texas. Built in 1928, it was the tallest building in San Antonio and the tallest brick and reinforced concrete structure in the United States standing at 280 feet (90 m). It is also known to be the first high-rise air-conditioned office building in the United States. The building was designed by George Willis, engineered by M.L. Diver, and constructed by L.T. Wright and Company. The building was named in honor of the Republic of Texas historical figure Benjamin Milam, noted for his leadership during the Texas Revolution. In keeping with that motif, the only flag that flies atop the tower is the Lone Star flag.

Paula Losoya Taylor was one of the founders of San Felipe Del Rio in Texas. Her hacienda in Del Rio became a major employer in the region, and an important gathering spot for worship, discussion, and more. Taylor donated land to create a Catholic cemetery, a fort, and schools in Del Rio.

There are more than 160 monuments and memorials to the Confederate States of America and associated figures that have been removed from public spaces in the United States, all but five of which have been since 2015. Some have been removed by state and local governments; others have been torn down by protestors.

The Portsmouth African Burying Ground is a memorial park on Chestnut Street in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, United States. The memorial park sits on top of an 18th century gravesite containing almost two hundred freed and enslaved African people. It is the only archeologically verified African burying ground for the time period in New England.

Frederick Douglass Memorial Park is a historic cemetery for African Americans in the Oakwood neighborhood of Staten Island, New York. It is named for abolitionist, orator, statesman, and author Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), although he is not buried there. It has burial sites for numerous prominent African Americans, including a pioneering journalist, athletes, musicians, performers, political leaders, and business people.

The Old San Antonio City Cemeteries Historic District, also known as the Eastside Cemetery Historic District, is a 103-acre complex collection of the oldest cemeteries in San Antonio, all established between 1853 and 1904. The individual cemeteries in the district were once part of land acreage that the City of San Antonio parceled off and sold to local churches and other organizations to be used as their private cemeteries. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.

The cemeteries are notable for their layout and size, their diversity of design, their funerary monuments, and for the array of community leaders interred there. While burials in 24 of the cemeteries are predominantly Anglo, seven cemeteries are solely or largely African American. There are scattered Hispanic burials, though the majority of Hispanics in the 19th century were interred in San Fernando Cemetery, established in ca. 1855 on San Antonio's west side.