Related Research Articles

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. Someone who engages in this study is called a linguist. See also the Outline of linguistics, the List of phonetics topics, the List of linguists, and the List of cognitive science topics. Articles related to linguistics include:

Southern or South Sámi is the southwesternmost of the Sámi languages, and is spoken in Norway and Sweden. It is an endangered language; the strongholds of this language are the municipalities of Snåsa, Røyrvik, Røros and Hattfjelldal in Norway. Of the approximately 2000 Southern Sami, only about 500 still speak fluent Southern Sami. This language belongs to the Saamic group within the Uralic language family.

Tzeltal or Tseltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

Wiyot or Soulatluk (lit. 'your jaw') is an Algic language spoken by the Wiyot people of Humboldt Bay, California. The language's last native speaker, Della Prince, died in 1962.

Goemai is an Afro-Asiatic language spoken in the Great Muri Plains region of Plateau State in central Nigeria, between the Jos Plateau and Benue River. Goemai is also the name of the ethnic group of speakers of the Goemai language. The name 'Ankwe' has been used to refer to the people, especially in older literature and to outsiders. As of 2020, it is estimated that there are around 380,000 Goemai speakers.

The Elgeyo language, or Kalenjin proper, are a dialect cluster of the Kalenjin branch of the Nilotic language family.

Kathlamet was a Chinookan language that was spoken around the border of Washington and Oregon by the Kathlamet people. The most extensive records of the language were made by Franz Boas, and a grammar was documented in the dissertation of Dell Hymes. It became extinct in the 1930s and there is little text left of it.

The Yimas language is spoken by the Yimas people, who populate the Sepik River Basin region of Papua New Guinea. It is spoken primarily in Yimas village, Karawari Rural LLG, East Sepik Province. It is a member of the Lower-Sepik language family. All 250-300 speakers of Yimas live in two villages along the lower reaches of the Arafundi River, which stems from a tributary of the Sepik River known as the Karawari River.

Misantla Totonac, also known as Yecuatla Totonac and Southeastern Totonac, is an indigenous language of Mexico, spoken in central Veracruz in the area between Xalapa and Misantla. It belongs to the Totonacan family and is the southernmost variety of Totonac. Misantla Totonac is highly endangered, with fewer than 133 speakers, most of whom are elderly. The language has largely been replaced by Spanish.

Southern Oromo, or Borana, is a variety of Oromo spoken in southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya by the Borana people. Günther Schlee also notes that it is the native language of a number of related peoples, such as the Sakuye.

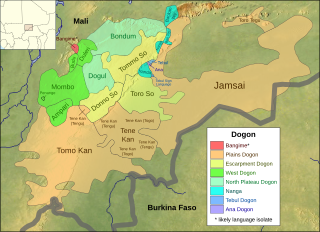

Bangime is a language isolate spoken by 3,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀. Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year. The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not. Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue. Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people. Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon. Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.

Estonian grammar is the grammar of the Estonian language.

Paamese, or Paama, is the language of the island of Paama in Northern Vanuatu. There is no indigenous term for the language; however linguists have adopted the term Paamese to refer to it. Both a grammar and a dictionary of Paamese have been produced by Terry Crowley.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, and one can refer to the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, determiners, participles, prepositions and postpositions, numerals, articles, etc., as declension.

The Hup language is one of the four Naduhup languages. It is spoken by the Hupda indigenous Amazonian peoples who live on the border between Colombia and the Brazilian state of Amazonas. There are approximately 1500 speakers of the Hup language. As of 2005, according to the linguist Epps, Hup is not seriously endangered – although the actual number of speakers is few, all Hupda children learn Hup as their first language.

Pech or Pesh is a Chibchan language spoken in Honduras. It was formerly known as Paya, and continues to be referred to in this manner by several sources, though there are negative connotations associated with this term. It has also been referred to as Seco. There are 300 speakers according to Yasugi (2007). It is spoken near the north-central coast of Honduras, in the Dulce Nombre de Culmí municipality of Olancho Department.

Tommo So is a language spoken in the eastern part of Mali's Mopti Region. It is placed under the Dogon language family, a subfamily of the Niger-Congo language family.

Tamashek or Tamasheq is a variety of Tuareg, a Berber macro-language widely spoken by nomadic tribes across North Africa in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Tamasheq is one of the three main varieties of Tuareg, the others being Tamajaq and Tamahaq.

Matlatzinca, or more specifically San Francisco Matlatzinca, is an endangered Oto-Manguean language of Western Central Mexico.[3] The name of the language in the language itself is pjiekak'joo.[4] The term "Matlatzinca" comes from the town's name in Nahuatl, meaning "the lords of the network." At one point, the Matlatzinca groups were called "pirindas," meaning "those in the middle."[5]

Swahili is a Bantu language which is native to or mainly spoken in the East African region. It has a grammatical structure that is typical for Bantu languages, bearing all the hallmarks of this language family. These include agglutinativity, a rich array of noun classes, extensive inflection for person, tense, aspect and mood, and generally a subject–verb–object word order.

References

- ↑ Di Carlo, Pierpaolo; Good, Jeff (30 October 2014). Endangered Languages. British Academy. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197265765.003.0012. ISBN 978-0-19-726576-5.

- ↑ "ISO 639-3 Registration Authority. Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code" (PDF). sil.org. 19 June 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ↑ Good et al. 2011, pp. 2, 9.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Lovegren 2013.

- 1 2 "Mungbam | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ↑ Good et al. 2011, p. 12.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Good et al. 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 30.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Good et al. 2011.

- ↑ Good et al. 2011, p. 21.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 44.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 23.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 186.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, pp. 197–199.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 42.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 91.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 354.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 197.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, pp. 205–208.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 206.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 207.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 205.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 209.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 190.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 111.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 121.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 118-119.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 157.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 83.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 84.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 341.

- ↑ Lovegren 2013, p. 291.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 150.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 176.

- 1 2 Lovegren 2013, p. 420.

Bibliography

- Good, Jeff; Lovegren, Jesse; Mve, Jean Patrick; Tchiemouo, Carine Nganguep; Voll, Rebecca; Di Carlo, Pierpaolo (2011). "The Languages of the Lower Fungom region of Cameroon" (PDF). The Languages of the Lower Fungom of Cameroon. University of Buffalo.

- Lovegren, Jesse Stuart James (2013). Mungbam Grammar (PDF) (PhD Dissertation). University of Buffalo.