Infant formula, baby formula or just formula or baby milk, infant milk, false milk, or first milk, is a manufactured food designed and marketed for feeding to babies and infants under 12 months of age, usually prepared for bottle-feeding or cup-feeding from powder or liquid. The U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) defines infant formula as "a food which purports to be or is represented for special dietary use solely as a food for infants by reason of its simulation of human milk or its suitability as a complete or partial substitute for human milk".

Nestlé S.A. is a Swiss multinational food and drink processing conglomerate corporation headquartered in Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland. It is the largest publicly held food company in the world, measured by revenue and other metrics, since 2014. It ranked No. 64 on the Fortune Global 500 in 2017 and No. 33 in the 2016 edition of the Forbes Global 2000 list of largest public companies.

Danone S.A. is a multinational food-products corporation based in Paris and founded in Barcelona, Spain. It is listed on Euronext Paris where it is a component of the CAC 40 stock market index. Some of the company's products are branded Dannon in the United States.

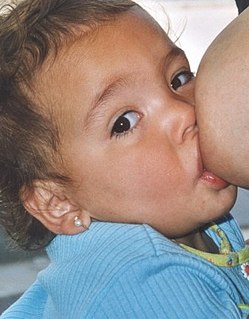

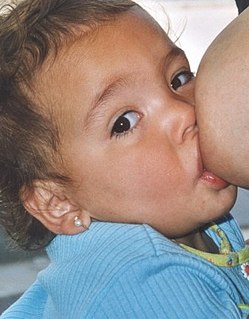

Breast milk or mother's milk is milk produced by mammary glands, located in the breast of a human female. Breast milk is the primary source of nutrition for newborns, containing fat, protein, carbohydrates and variable minerals and vitamins. Breast milk also contains factors that are important for implications protecting the infant against infection and inflammation, whilst also contributing to healthy development of the immune system and gut microbiome.

Baby food is any soft, easily consumed food other than breastmilk or infant formula that is made specifically for human babies between four and six months and two years old. The food comes in many varieties and flavors that are purchased ready-made from producers, or it may be table food eaten by the family that has been mashed or otherwise broken down.

The International Baby Food Action Network, IBFAN, consists of public interest groups working around the world to reduce infant and young child morbidity and mortality. IBFAN aims to improve the health and well-being of babies and young children, their mothers and their families through the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding and optimal infant feeding practices. IBFAN works for universal and full implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes and Resolutions.

The International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes is an international health policy framework for breastfeeding promotion adopted by the World Health Assembly (WHA) of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1981. The Code was developed as a global public health strategy and recommends restrictions on the marketing of breast milk substitutes, such as infant formula, to ensure that mothers are not discouraged from breastfeeding and that substitutes are used safely if needed. The Code also covers ethical considerations and regulations for the marketing of feeding bottles and teats. A number of subsequent WHA resolutions have further clarified or extended certain provisions of the Code.

Consumers International is the membership organization for consumer groups around the world. Founded on 1 April 1960, it has over 250 member organizations in 120 countries. Its head office is situated in London, England, and has numerous regional offices in Latin America, Asia Pacific, Middle East and Africa.

Derrick B. Jelliffe and his wife Eleanore. F. Patrice Jelliffe – known as Dick and Pat Jelliffe – were experts in tropical paediatrics and infant nutrition. They are most known for their seminal book, Human Milk in the Modern World, published by Oxford University Press in 1978, and for editing the multi-volume Advances in International Maternal and Child Health. The Jelliffes also wrote over 500 scholarly papers, often together, and 22 books. They lived and worked in England, Africa, India, the Caribbean and settled in Los Angeles, where he held the Chair in Public Health and Paediatrics at the University of California from 1972 to 1990.

The World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA) is a network of people working on a global scale to eliminate obstacles to breastfeeding and to act on the Innocenti Declaration. The groups within this alliance tackle the problems from a variety of perspectives or point of views, such as consumer advocates, mothers, and lactation consultants.

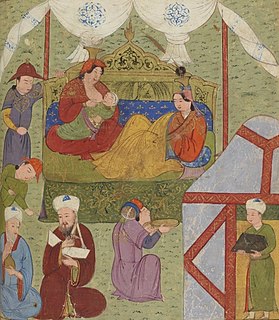

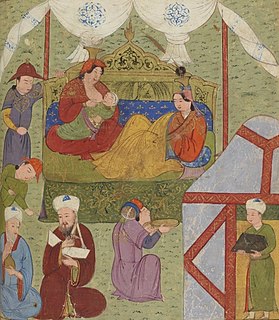

The history and culture of breastfeeding traces changing social, medical and legal attitudes to breastfeeding, the act of feeding a child breast milk directly from breast to mouth. Breastfeeding may be performed by the infant's mother or by a surrogate, typically called a wet nurse.

Lactivism is the doctrine or practice of vigorous action or involvement as a means of achieving a breastfeeding culture, sometimes by demonstrations, protests, etc. of breastfeeding. Supporters, referred to as "lactivists", seek to protest the violation of International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes by formula companies and industry.

Breastfeeding, or nursing, is the process by which human breast milk is fed to a child. Breast milk may be from the breast, or may be expressed by hand or pumped and fed to the infant. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that breastfeeding begin within the first hour of a baby's life and continue as often and as much as the baby wants. Health organizations, including the WHO, recommend breastfeeding exclusively for six months. This means that no other foods or drinks, other than vitamin D, are typically given. After the introduction of foods at six months of age, recommendations include continued breastfeeding until one to two years of age or more. Globally, about 38% of infants are exclusively breastfed during their first six months of life.

Breastfeeding promotion refers to coordinated activities and policies to promote health among women, newborns and infants through breastfeeding.

The Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), also known as Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI), is a worldwide programme of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), launched in 1992 in India following the adoption of the Innocenti Declaration on breastfeeding promotion in 1990. The initiative is a global effort for improving the role of maternity services to enable mothers to breastfeed babies for the best start in life. It aims at improving the care of pregnant women, mothers and newborns at health facilities that provide maternity services for protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding, in accordance with the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.

In Western countries extended breastfeeding usually means breastfeeding after the age of 12 to 24 months, depending on the culture.

Infant nutrition is the description of the dietary needs of infants. A diet lacking essential calories, minerals, vitamins, or fluids is considered inadequate. Breast milk provides the best nutrition for these vital first months of growth when compared to infant formula. For example, breastfeeding aids in preventing anemia, obesity, and sudden infant death syndrome; and it promotes digestive health, immunity, intelligence, and dental development. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusively feeding an infant breast milk, or iron-fortified formula, for the first six months of life and continuing for one year or longer as desired by infant and mother. Infants are usually not introduced to solid foods until four to six months of age. Historically, breastfeeding infants was the only option for nutrition otherwise the infant would perish. Breastfeeding is rarely contraindicated, but is not recommended for mothers being treated for cancer, those with active tuberculosis, HIV, substance abuse, or leukemia. Clinicians can be consulted to determine what the best source of infant nutrition is for each baby.

BabyNes is a beverage machine by Nestlé that makes infant formula from single-use capsules, similar to Nestlé's Nespresso. The product was designed to recreate Nespresso's success with coffee in the baby formula industry. It was first introduced in Switzerland on May 25, 2011. The Wall Street Journal referred to Nespresso as Nestlé's fastest growing brand in 2011 after its sales rose by 20% in 2010 and it brought a number of legal actions against competitors. Nestlé reported strong sales for the product in late 2011.

Natividad Relucio Clavano was a Filipino paediatrician. As chief of paediatrics at Baguio General Hospital, she studied the benefits of breastfeeding over infant formula and reformed the model of care provided to newborns and their mothers.

Gabrielle Palmer BA, MSc has been involved in international efforts to stop the unethical promotion of breastmilk substitutes globally and to support appropriate infant feeding for over 40 years. She is the author of the seminal text, The Politics of Breastfeeding, now in its revised third edition and which has never been out of print.