Related Research Articles

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Cædmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known. A Northumbrian cowherd who cared for the animals at the double monastery of Streonæshalch during the abbacy of St. Hilda, he was originally ignorant of "the art of song" but learned to compose one night in the course of a dream, according to the 8th-century historian Bede. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational Christian poet.

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principle ornamental device to help indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly studied traditions of alliterative verse are those found in the oldest literature of the Germanic languages, where scholars use the term 'alliterative poetry' rather broadly to indicate a tradition which not only shares alliteration as its primary ornament but also certain metrical characteristics. The Old English epic Beowulf, as well as most other Old English poetry, the Old High German Muspilli, the Old Saxon Heliand, the Old Norse Poetic Edda, and many Middle English poems such as Piers Plowman, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and the Alliterative Morte Arthur all use alliterative verse.

The Old English poem Judith describes the beheading of Assyrian general Holofernes by Israelite Judith of Bethulia. It is found in the same manuscript as the heroic poem Beowulf, the Nowell Codex, dated ca. 975–1025. The Old English poem is one of many retellings of the Holofernes–Judith tale as it was found in the Book of Judith, still present in the Catholic and Orthodox Christian Bibles. The other extant version is by Ælfric of Eynsham, late 10th-century Anglo-Saxon abbot and writer; his version is a homily of the tale.

"Widsith", also known as "The Traveller's Song", is an Old English poem of 143 lines. It survives only in the Exeter Book, a manuscript of Old English poetry compiled in the late-10th century, which contains approximately one-sixth of all surviving Old English poetry. "Widsith" is located between the poems "Vainglory" and "The Fortunes of Men". Since the donation of the Exeter Book in 1076, it has been housed in Exeter Cathedral in southwestern England. The poem is for the most part a survey of the people, kings, and heroes of Europe in the Heroic Age of Northern Europe.

The Junius manuscript is one of the four major codices of Old English literature. Written in the 10th century, it contains poetry dealing with Biblical subjects in Old English, the vernacular language of Anglo-Saxon England. Modern editors have determined that the manuscript is made of four poems, to which they have given the titles Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, and Christ and Satan. The identity of their author is unknown. For a long time, scholars believed them to be the work of Cædmon, accordingly calling the book the Cædmon manuscript. This theory has been discarded due to the significant differences between the poems.

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis or Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, is a large codex of Old English poetry, believed to have been produced in the late tenth century AD. It is one of the four major manuscripts of Old English poetry, along with the Vercelli Book in Vercelli, Italy, the Nowell Codex in the British Library, and the Junius manuscript in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The book was donated to what is now the Exeter Cathedral library by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, in 1072. It is believed originally to have contained 130 or 131 leaves, of which the first 7 or 8 have been replaced with other leaves; the original first 8 leaves are lost. The Exeter Book is the largest and perhaps oldest known manuscript of Old English literature, containing about a sixth of the Old English poetry that has come down to us.

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German. It is a West Germanic language, closely related to the Anglo-Frisian languages. It is documented from the 8th century until the 12th century, when it gradually evolved into Middle Low German. It was spoken throughout modern northwestern Germany, primarily in the coastal regions and in the eastern Netherlands by Saxons, a Germanic tribe that inhabited the region of Saxony. It partially shares Anglo-Frisian's Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law which sets it apart from Low Franconian and Irminonic languages, such as Dutch, Luxembourgish and German.

The Heliand is an epic poem in Old Saxon, written in the first half of the 9th century. The title means saviour in Old Saxon, and the poem is a Biblical paraphrase that recounts the life of Jesus in the alliterative verse style of a Germanic epic. Heliand is the largest known work of written Old Saxon.

Rune poems are poems that list the letters of runic alphabets while providing an explanatory poetic stanza for each letter. Three different poems have been preserved: the Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem, the Norwegian Rune Poem, and the Icelandic Rune Poem.

Narfi, also Nörfi, Nari or Nörr, is a jötunn in Norse mythology, and the father of Nótt, the personified night.

Eduard Sievers was a philologist of the classical and Germanic languages. Sievers was one of the Junggrammatiker of the so-called "Leipzig School". He was one of the most influential historical linguists of the late nineteenth century. He is known for his recovery of the poetic traditions of Germanic languages such as Anglo-Saxon and Old Saxon, as well as for his discovery of Sievers' law.

Franciscus Junius, also known as François du Jon, was a pioneer of Germanic philology. As a collector of ancient manuscripts, he published the first modern editions of a number of important texts. In addition, he wrote the first comprehensive overview of ancient writings on the visual arts, which became a cornerstone of classical art theories throughout Europe.

Genesis A is an Old English poetic adaptation of the first half or so of the biblical book of Genesis. The poem is fused with a passage known today as Genesis B, translated and interpolated from the Old Saxon Genesis.

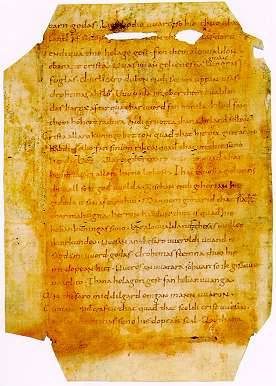

Genesis B, also known as The Later Genesis, is a passage of Old English poetry describing the Fall of Satan and the Fall of Man, translated from an Old Saxon poem known as the Old Saxon Genesis. The passage known as Genesis B survives as an interpolation in a much longer Old English poem, the rest of which is known as Genesis A, which gives an otherwise fairly faithful translation of the biblical Book of Genesis. Genesis B comprises lines 235-851 of the whole poem.

"Waldere" or "Waldhere" is the conventional title given to two Old English fragments, of around 32 and 31 lines, from a lost epic poem, discovered in 1860 by E. C. Werlauff, Librarian, in the Danish Royal Library at Copenhagen, where it is still preserved. The parchment pages had been reused as stiffening in the binding of an Elizabethan prayer book, which had presumably come to Europe following the Dissolution of the Monasteries in England in the 16th century.

The Nine Herbs Charm, Nigon Wyrta Galdor, Lay of the Nine Healing Herbs, or Nine Wort Spell is an Old English charm recorded in the tenth-century CE Anglo-Saxon medical compilation known as Lacnunga, which survives on the manuscript, Harley MS 585, in the British Library, in London. The charm involves the preparation of nine plants.

Cædmon's Hymn is a short Old English poem attributed to Cædmon, a supposedly illiterate and unmusical cow-herder who was, according to the Northumbrian monk Bede, miraculously empowered to sing in honour of God the Creator. The poem is Cædmon's only known composition.

Ernst Eduard Martin was a German philologist of Romance and Germanic studies. He was the son of gynecologist Eduard Arnold Martin (1809–1875).

Exeter Book Riddle 30 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Since the suggestion of F. A. Blackburn in 1901, its solution has been agreed to be the Old English word bēam, understood both in its primary sense 'tree' but also in its secondary sense 'cross'.

References

- ↑ Alger N. Doane, The Saxon Genesis: An Edition of the West Saxon 'Genesis B' and the Old Saxon Vatican 'Genesis', Madison, Wisconsin / London: University of Wisconsin, 1991, ISBN 9780299128005, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Doane, p. 46.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Doane, p. 7; Eduard Sievers, Der Heliand und die angelsächsische Genesis, Halle: Niemeyer, 1875, OCLC 2221124 (in German)

- ↑ Karl Breul, "Eduard Sievers", The Modern Quarterly of Language and Literature 1.3 (1898) 173–75, p. 174.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Doane, p. 7.

- ↑ Doane, p. 13.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Seiichi Suzuki, The Metre of Old Saxon Poetry: The Remaking of Alliterative Tradition, Cambridge / Rochester, New York: D. S. Brewer, 2004, ISBN 9781843840145, p. 365.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Peter J. Lucas, "Some Aspects of "Genesis B" as Old English Verse", Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C, Volume 88 (1988) 143–78, p. 172.

- ↑ Andrew Cole, "Jewish Apocrypha and Christian Epistemologies of the Fall: The Dialogi of Gregory the Great and the Old Saxon Genesis", in Rome and the North: The Early Reception of Gregory the Great in Germanic Europe, ed. Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr., Kees Dekker and David F. Johnson, Mediaevalia Groningana new series 4, Paris / Sterling, Virginia: Peeters, 2001, ISBN 9789042910546, pp. 157–88, pp. 158–59.

- ↑ Thomas D. Hill, "Pilate's Visionary Wife and the Innocence of Eve: An Old Saxon Source for the Old English Genesis B", The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 101.2 (2002) 170–84, pp. 171, 173.

- ↑ Cole, pp. 159 – 60, 187.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Thomas N. Hall, The Saxon Genesis: An Edition of the West Saxon "Genesis B" and the Old Saxon "Vatican Genesis". by A. N. Doane. Review, The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 94.5 (1995) 556–59, p. 558.

- ↑ Hill, p. 181.

- ↑ Doane, pp. 102–06.

- ↑ Hill, pp. 178–79, 183.