Mehmed II, commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror, was an Ottoman sultan who ruled from August 1444 to September 1446, and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

Year 1480 (MCDLXXX) was a leap year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

The fall of Constantinople, also known as the conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun on 6 April.

Otranto is a coastal town, port and comune in the province of Lecce, in a fertile region once famous for its breed of horses.

Cem Sultan or Sultan Cem or Şehzade Cem, was a claimant to the Ottoman throne in the 15th century.

The Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire concerns the history of the Ottoman Empire from the Conquest of Constantinople in 1453 until the second half of the sixteenth century, roughly the end of the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. During this period a system of patrimonial rule based on the absolute authority of the sultan reached its apex, and the empire developed the institutional foundations which it would maintain, in modified form, for several centuries. The territory of the Ottoman Empire greatly expanded, and led to what some historians have called the Pax Ottomana. The process of centralization undergone by the empire prior to 1453 was brought to completion in the reign of Mehmed II.

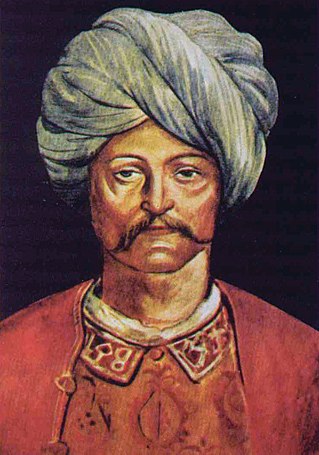

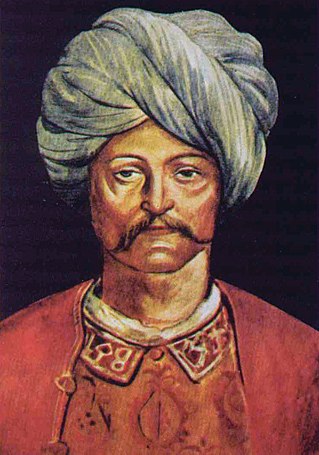

Gedik Ahmed Pasha was an Ottoman statesman and admiral who served as Grand Vizier and Kapudan Pasha during the reigns of sultans Mehmed II and Bayezid II.

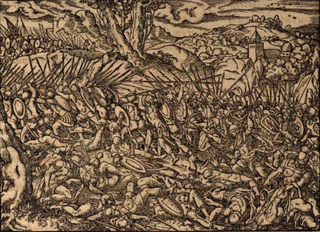

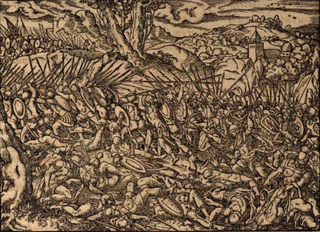

The second siege of Krujë took place from 1466 to 1467. Sultan Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire led an army into Albania to defeat Skanderbeg, the leader of the League of Lezhë, which was created in 1444 after he began his war against the Ottomans. During the almost year-long siege, Skanderbeg's main fortress, Krujë, withstood the siege while Skanderbeg roamed Albania to gather forces and facilitate the flight of refugees from the civilian areas that were attacked by the Ottomans. Krujë managed to withstand the siege put on it by Ballaban Badera, sanjakbey of the Sanjak of Ohrid, an Albanian brought up in the Ottoman army through the devşirme. By 23 April 1467, the Ottoman army had been defeated and Skanderbeg entered Krujë.

Leonardo III Tocco was the last ruler of the Despotate of Epirus, ruling from the death of his father Carlo II Tocco in 1448 to the despotate's fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1479. Leonardo was one of the last independent Latin rulers in Greece and the last to hold territories on the Greek mainland. After the fall of his realm, Leonardo fled to Italy and became a landowner and diplomat. He continued to claim his titles in exile until his death.

Gjergj Kastrioti, commonly known as Skanderbeg, was an Albanian feudal lord and military commander who led a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in what is today Albania, North Macedonia, Greece, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Serbia.

The Ottoman–Hungarian Wars were a series of battles between the Ottoman Empire and the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Following the Byzantine Civil War, the Ottoman capture of Gallipoli, and the decisive Battle of Kosovo, the Ottoman Empire was poised to conquer the entirety of the Balkans and also sought and expressed desire to expand further north into Central Europe beginning with the Hungarian lands.

Italy-Turkey relations are the relations between Italy and Turkey. Both countries are members of NATO and the Union for the Mediterranean and have active diplomatic relations. Italy is a member of the European Union, Turkey is not a member.

Mesih Pasha or Misac Pasha was an Ottoman of Eastern Roman origin, being a nephew of the last Roman emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos. He served as Kapudan Pasha of the Ottoman Navy and was Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire in 1501.

Gjon II Kastrioti, was the son of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the Albanian national hero, and of Donika Kastrioti, daughter of the powerful Albanian prince, Gjergj Arianiti. He was for a short time Lord of Kruja after his father's death, then Duke of San Pietro in Galatina (1485), Count of Soleto, Signore of Monte Sant'Angelo and San Giovanni Rotondo. In 1495, Ferdinand I of Naples gave him the title of the Signore of Gagliano del Capo and Oria. While in his teens, he was forced to leave the country after the death of his father in 1468. He is known also for his role in the Albanian Uprisings of 1481, when, after reaching the Albanian coast from Italy, settling in Himara, he led a rebellion against the Ottomans. In June 1481, he supported forces of Ivan Crnojević to successfully recapture Zeta from the Ottomans. He was unable to re-establish the Kastrioti Principality and liberate Albania from the Ottomans, and he retired in Italy after three years of war in 1484.

The Battle of Ohrid took place on 14 or 15 September 1464 between Albanian ruler Skanderbeg's forces and Ottoman forces. A crusade against Sultan Mehmed II had been planned by Pope Pius II with Skanderbeg as one of its main leaders. The battle near Ohrid occurred as a result of an Albanian incursion into Ottoman territory. The Ottomans stationed in the area were assaulted by Skanderbeg's men and 1,000 Venetian soldiers under Cimarosto. The Ottomans were lured out of their protections in Ohrid and ambushed by the Albanian cavalry. Skanderbeg won the resulting battle and his men earned 40,000 ducats after captured Ottoman officers were ransomed. Pius II died before the planned crusade began, however, forcing Skanderbeg to fight his battles virtually alone.

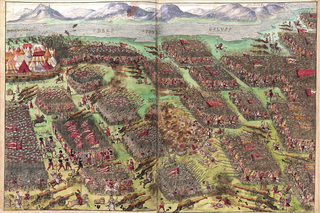

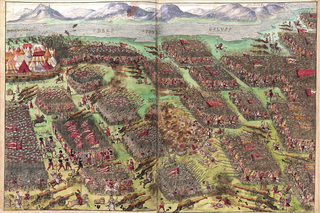

The siege of Shkodra took place from May 1478 to April 1479 as a confrontation between the Ottoman Empire and the Venetians together with the League of Lezhe and other Albanians at Shkodra and its Rozafa Castle during the First Ottoman-Venetian War (1463–1479). Ottoman historian Franz Babinger called the siege "one of the most remarkable episodes in the struggle between the West and the Crescent". A small force of approximately 1,600 Albanian and Italian men and a much smaller number of women faced a massive Ottoman force containing artillery cast on site and an army reported to have been as many as 350,000 in number. The campaign was so important to Mehmed II "the Conqueror" that he came personally to ensure triumph. After nineteen days of bombarding the castle walls, the Ottomans launched five successive general attacks which all ended in victory for the besieged. With dwindling resources, Mehmed attacked and defeated the smaller surrounding fortresses of Žabljak Crnojevića, Drisht, and Lezha, left a siege force to starve Shkodra into surrender, and returned to Constantinople. On January 25, 1479, Venice and Constantinople signed a peace agreement that ceded Shkodra to the Ottoman Empire. The defenders of the citadel emigrated to Venice, whereas many Albanians from the region retreated into the mountains. Shkodra then became a seat of the newly established Ottoman sanjak, the Sanjak of Scutari. The Ottomans held the city until Montenegro captured it in April 1913, after a six-month siege.

The Martyrs of Otranto, also known as Saints Antonio Primaldo and his Companions, were 813 inhabitants of Otranto, Salento, Apulia, in southern Italy, who were killed on 14 August 1480 after the city had fallen to an Ottoman force under Gedik Ahmed Pasha. According to a traditional account, the killings took place after the citizens had refused to convert to Islam.

Stefano Pendinelli was the Roman Catholic archbishop of Otranto, Italy. He was slain in 1480, along with all his priests, by the Ottoman force that invaded Otranto. He is among the 813 martyrs of Otranto canonized by Pope Francis in 2013.

The Portuguese expedition to Otranto in 1481, which the Portuguese call the Turkish Crusade, arrived too late to participate in any fighting. On 8 April 1481, Pope Sixtus IV issued the papal bull Cogimur iubente altissimo, which called for a crusade against the Ottomans, who had occupied Otranto, in southern Italy. The Pope's intention was that after recapturing Otranto, the crusaders would cross the Adriatic and liberate Vlorë (Valona) as well.

Andreas Palaiologos or Palaeologus, sometimes anglicized to Andrew, was a son of Manuel Palaiologos. Andreas was likely named after his uncle, Manuel's brother, Andreas Palaiologos. Andreas's father had returned from exile under the protection of the Papacy to Constantinople in 1476 and had been generously provided for by Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire, who had conquered the city from Manuel's relatives in 1453. Although Manuel remained a Christian until his death at some point before 1512, Andreas converted to Islam and served as an Ottoman court official under the name Mehmet Pasha. He was the last certain member of the imperial branch of the Palaiologos family.