United States v. Klein, 80 U.S. 128 (1871), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case stemming from the American Civil War (1861–1865).

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 (FSIA) is a United States law, codified at Title 28, §§ 1330, 1332, 1391(f), 1441(d), and 1602–1611 of the United States Code, that established criteria as to whether a foreign sovereign nation is immune from the jurisdiction of U.S. courts—federal or state. The Act also establishes specific procedures for service of process, attachment of property and execution of judgment in proceedings against a foreign state. The FSIA provides the exclusive basis and means to bring a civil suit against a foreign sovereign in the United States. It was signed into law by United States President Gerald Ford on October 21, 1976.

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that Article One of the U.S. Constitution did not give the United States Congress the power to abrogate the sovereign immunity of the states that is further protected under the Eleventh Amendment. Such abrogation is permitted where it is necessary to enforce the rights of citizens guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment as per Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer. The case also held that the doctrine of Ex parte Young, which allows state officials to be sued in their official capacity for prospective injunctive relief, was inapplicable under these circumstances, because any remedy was limited to the one that Congress had provided.

Alperin v. Vatican Bank was an unsuccessful class action suit by Holocaust survivors brought against the Vatican Bank and the Franciscan Order filed in San Francisco, California, on November 15, 1999. The case was initially dismissed as a political question by the District Court for the Northern District of California in 2003, but was reinstated in part by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 2005. That ruling attracted attention as a precedent at the intersection of the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA) and the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA).

In the United States, qualified immunity is a legal principle of federal constitutional law that grants government officials performing discretionary (optional) functions immunity from lawsuits for damages unless the plaintiff shows that the official violated "clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known". It is a form of sovereign immunity less strict than absolute immunity that is intended to protect officials who "make reasonable but mistaken judgments about open legal questions", extending to "all [officials] but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law". Qualified immunity applies only to government officials in civil litigation, and does not protect the government itself from suits arising from officials' actions.

Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm, Inc., 514 U.S. 211 (1995), was a landmark case about separation of powers in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that Congress may not retroactively require federal courts to reopen final judgments. Writing for the Court, Justice Scalia asserted that such action amounted to an unauthorized encroachment by Congress upon the powers of the judiciary and therefore violated the constitutional principle of separation of powers.

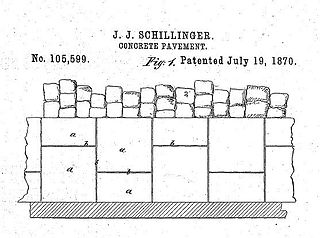

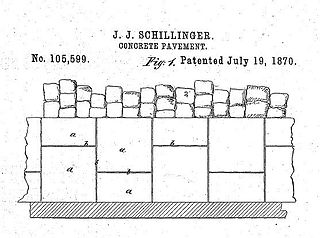

Schillinger v. United States, 155 U.S. 163 (1894), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, holding that a suit for patent infringement cannot be entertained against the United States, because patent infringement is a tort and the United States has not waived sovereign immunity for intentional torts.

In United States law, the federal government as well as state and tribal governments generally enjoy sovereign immunity, also known as governmental immunity, from lawsuits. Local governments in most jurisdictions enjoy immunity from some forms of suit, particularly in tort. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act provides foreign governments, including state-owned companies, with a related form of immunity—state immunity—that shields them from lawsuits except in relation to certain actions relating to commercial activity in the United States. The principle of sovereign immunity in US law was inherited from the English common law legal maxim rex non potest peccare, meaning "the king can do no wrong." In some situations, sovereign immunity may be waived by law.

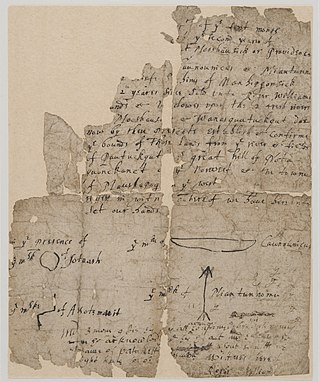

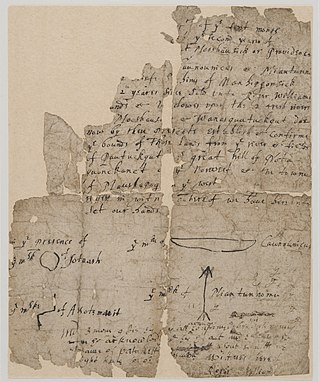

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

United States v. Bormes, 568 U.S. 6 (2012), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States holding that the Little Tucker Act, which provides jurisdiction to federal courts for certain claims brought against the federal government, does not apply to lawsuits brought under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, 572 U.S. 782 (2014), was a United States Supreme Court case examining whether a federal court has jurisdiction over activity that violates the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act but takes place off Indian lands, and, if so, whether tribal sovereign immunity prevents a state from suing in federal court. In a 5–4 decision, the Court held that the State of Michigan's suit against Bay Mills is barred by tribal immunity.

The Gun Lake Trust Land Reaffirmation Act is an act of Congress that reaffirmed the status of lands taken into trust by the Department of the Interior (DOI) for the benefit of the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians in the state of Michigan.

The Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (CRCA) is a United States copyright law that attempted to abrogate sovereign immunity of states for copyright infringement. The CRCA amended 17 USC 511(a):

In general. Any State, any instrumentality of a State, and any officer or employee of a State or instrumentality of a State acting in his or her official capacity, shall not be immune, under the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution of the United States or under any other doctrine of sovereign immunity, from suit in Federal Court by any person, including any governmental or nongovernmental entity, for a violation of any of the exclusive rights of a copyright owner provided by sections 106 through 122, for importing copies of phonorecords in violation of section 602, or for any other violation under this title.

Bank Markazi v. Peterson, 578 U.S. ___ (2016), was a United States Supreme Court case that found that a law which only applied to a specific case, identified by docket number, and eliminated all of the defenses one party had raised does not violate the separation of powers in the United States Constitution between the legislative (Congress) and judicial branches of government. The plaintiffs, in the case had initially obtained judgments against Iran for its role in supporting state-sponsored terrorism, particularly the 1983 Beirut barracks bombings and 1996 Khobar Towers bombing, and sought execution against a bank account in New York held, through European intermediaries, on behalf of Bank Markazi, the Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The plaintiffs obtained court orders preventing the transfer of funds from the account in 2008 and initiated their lawsuit in 2010. Bank Markazi raised several defenses, including that the account was not an asset of the bank, but rather an asset of its European intermediary, under both New York state property law and §201(a) of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act. In response to concerns that existing laws were insufficient for the account to be used to settle the judgments, Congress added an amendment to a 2012 bill, codified after enactment as 22 U.S.C. § 8772, that identified the pending lawsuit by docket number, applied only to the assets in the identified case, and effectively abrogated every legal basis available to Bank Markazi to prevent the plaintiffs from executing their claims against the account. Bank Markazi then argued that § 8772 was an unconstitutional breach of the separation of power between the legislative and judicial branches of government, because it effectively directed a particular result in a single case without changing the generally applicable law. The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and, on appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit both upheld the constitutionality of § 8772 and cleared the way for the plaintiffs to execute their judgments against the account, which held about $1.75 billion in cash.

Jesner v. Arab Bank, PLC, No. 16-499, 584 U.S. ___ (2018), was a case from the United States Supreme Court which addressed the issue of corporate liability under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS). Plaintiffs alleged that Arab Bank facilitated terrorist attacks by transferring funds to terrorist groups in the Middle East, some of which passed through Arab Bank's offices in New York City.

Jam v. International Finance Corp., 586 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case from the October 2018 term. The Supreme Court ruled that international organizations, such as the World Bank Group's financing arm, the International Finance Corporation, can be sued in US federal courts for conduct arising from their commercial activities. It specifically held that international organizations shared the same sovereign immunity as foreign governments. This was a reversal from existing jurisprudence, which held that international organizations had near-absolute immunity from lawsuits under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act and the International Organizations Immunities Act.

Home Depot U. S. A., Inc. v. Jackson, 587 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case which determined that a third-party defendant to a counterclaim submitted in a state-court civil action cannot remove their case to federal court. The Court explained, in a 5–4 decision, that although a third-party counterclaim defendant is a "defendant to a claim," removal can only be performed by the defendant to a "civil action." And this holds true even when the counterclaim is in the form of a class action. The Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 permits removal by "any defendant to a class action" but this does not extend removal rights to a third-party counterclaim defendant because they are not a defendant to the original case.

BP P.L.C. v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 593 U.S. ___ (2021), was a case in the United States Supreme Court dealing with matters of jurisdiction of various climate change lawsuits in the United States judicial system.

Whole Woman's Health v. Jackson, 595 U.S. ___ (2021), was a United States Supreme Court case brought by Texas abortion providers and abortion rights advocates that challenged the constitutionality of the Texas Heartbeat Act, a law that outlaws abortions after six weeks. The Texas Heartbeat Act prohibits state officials from enforcing the ban but authorizes private individuals to enforce the law by suing anyone who performs, aids, or abets an abortion after six weeks. The law was structured this way to evade pre-enforcement judicial review because lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of state statutes are typically brought against state officials who are charged with enforcing the law, as the state itself cannot be sued under the doctrine of sovereign immunity.

Garland v. Gonzalez, 596 U.S. ___ (2022), was a United States Supreme Court case related to immigration detention.