Sovereign immunity, or crown immunity, is a legal doctrine whereby a sovereign or state cannot commit a legal wrong and is immune from civil suit or criminal prosecution, strictly speaking in modern texts in its own courts. State immunity is a similar, stronger doctrine, that applies to foreign courts.

The Eleventh Amendment is an amendment to the United States Constitution which was passed by Congress on March 4, 1794, and ratified by the states on February 7, 1795. The Eleventh Amendment restricts the ability of individuals to bring suit against states of which they are not citizens in federal court.

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 (FSIA) is a United States law, codified at Title 28, §§ 1330, 1332, 1391(f), 1441(d), and 1602–1611 of the United States Code, that established criteria as to whether a foreign sovereign state is immune from the jurisdiction of the United States' federal or state courts. The Act also establishes specific procedures for service of process, attachment of property and execution of judgment in proceedings against a foreign state. The FSIA provides the exclusive basis and means to bring a civil suit against a foreign sovereign in the United States. It was signed into law by United States President Gerald Ford on October 21, 1976.

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court determining that the Eleventh Amendment prohibits a citizen of a U.S. state to sue that state in a federal court. Citizens cannot bring suits against their own state for cases related to the federal constitution and federal laws. The court left open the question of whether a citizen may sue his or her state in state courts. That ambiguity was resolved in Alden v. Maine (1999), in which the Court held that a state's sovereign immunity forecloses suits against a state government in state court.

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974), was a United States Supreme Court case that held that the sovereign immunity recognized in the Eleventh Amendment prevented a federal court from ordering a state from paying back funds that had been unconstitutionally withheld from parties to whom they had been due.

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that Article One of the U.S. Constitution did not give the United States Congress the power to abrogate the sovereign immunity of the states that is further protected under the Eleventh Amendment. Such abrogation is permitted where it is necessary to enforce the rights of citizens guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment as per Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer. The case also held that the doctrine of Ex parte Young, which allows state officials to be sued in their official capacity for prospective injunctive relief, was inapplicable under these circumstances, because any remedy was limited to the one that Congress had provided.

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976), was a United States Supreme Court decision that determined that the U.S. Congress has the power to abrogate the Eleventh Amendment sovereign immunity of the states, if this is done pursuant to its Fourteenth Amendment power to enforce upon the states the guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The abrogation doctrine is a US constitutional law doctrine expounding when and how the Congress may waive a state's sovereign immunity and subject it to lawsuits to which the state has not consented.

The Tucker Act is a federal statute of the United States by which the United States government has waived its sovereign immunity with respect to certain lawsuits.

Central Virginia Community College v. Katz, 546 U.S. 356 (2006), is a United States Supreme Court case holding that the Bankruptcy Clause of the Constitution abrogates state sovereign immunity. It is significant as one of only three cases allowing Congress to use an Article I power to authorize individuals to sue states, the others being PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey and Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety.

Alden v. Maine, 527 U.S. 706 (1999), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States about whether the United States Congress may use its Article I powers to abrogate a state's sovereign immunity from suits in its own courts, thereby allowing citizens to sue a state in state court without the state's consent.

Dolan v. United States Postal Service, 546 U.S. 481 (2006), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States, involving the extent to which the United States Postal Service has sovereign immunity from lawsuits brought by private individuals under the Federal Tort Claims Act. The Court ruled that an exception to the FTCA that barred liability for the "negligent transmission of mail" did not apply to a claim for injuries caused when someone tripped over mail left by a USPS employee. Instead, the exception only applied to damage caused to the mail itself or that resulted from its loss or delay.

Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents, 528 U.S. 62 (2000), was a US Supreme Court case that determined that the US Congress's enforcement powers under the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution did not extend to the abrogation of state sovereign immunity under the Eleventh Amendment over complaints of discrimination that is rationally based on age.

College Savings Bank v. Florida Prepaid Postsecondary Education Expense Board, 527 U.S. 666 (1999), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States relating to the doctrine of sovereign immunity.

Ali v. Federal Bureau of Prisons, 552 U.S. 214 (2008), was a United States Supreme Court case, upholding the United States's sovereign immunity against tort claims brought when "any law enforcement officer" loses a person's property. It was argued on October 29, 2007, and decided on January 22, 2008, by the Roberts Court.

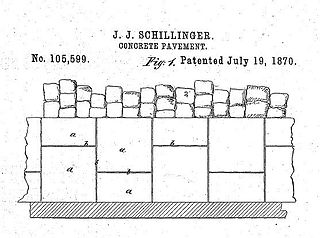

Schillinger v. United States, 155 U.S. 163 (1894), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, holding that a suit for patent infringement cannot be entertained against the United States, because patent infringement is a tort and the United States has not waived sovereign immunity for intentional torts.

Atascadero State Hospital v. Scanlon, 473 U.S. 234 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding Congress' power to abrogate the Eleventh Amendment sovereign immunity of the states.

Millbrook v. United States, 569 U.S. 50 (2013), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that holds that the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) waives the sovereign immunity of the United States for certain intentional torts committed by law enforcement officers. The unanimous opinion, delivered by Justice Clarence Thomas, holds that law enforcement "employment" duties are not limited to searches, seizures of evidence, or arrests, and, as such, the petitioner can sue. As this case revolved around sovereign immunity waivers and not the merits, the Court did not decide upon the merits of the lawsuits.

The Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (CRCA) is a United States copyright law that attempted to abrogate sovereign immunity of states for copyright infringement. The CRCA amended 17 USC 511(a):

In general. Any State, any instrumentality of a State, and any officer or employee of a State or instrumentality of a State acting in his or her official capacity, shall not be immune, under the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution of the United States or under any other doctrine of sovereign immunity, from suit in Federal Court by any person, including any governmental or nongovernmental entity, for a violation of any of the exclusive rights of a copyright owner provided by sections 106 through 122, for importing copies of phonorecords in violation of section 602, or for any other violation under this title.

Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt, 587 U.S. 230 (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case that determined that unless they consent, states have sovereign immunity from private suits filed against them in the courts of another state. The 5–4 decision overturned precedent set in a 1979 Supreme Court case, Nevada v. Hall. This was the third time that the litigants had presented their case to the Court, as the Court had already ruled on the issue in 2003 and 2016.