Frederick III was Holy Roman Emperor from 1452 until his death. He was the fourth king and first emperor of the House of Habsburg. He was the penultimate emperor to be crowned by the pope, and the last to be crowned in Rome.

The House of Habsburg, alternatively spelled Hapsburg in English and also known as the House of Austria, is one of the most prominent and important dynasties in European history.

Maximilian II was Holy Roman Emperor from 1564 until his death in 1576. A member of the Austrian House of Habsburg, he was crowned King of Bohemia in Prague on 14 May 1562 and elected King of Germany on 24 November 1562. On 8 September 1563 he was crowned King of Hungary and Croatia in the Hungarian capital Pressburg. On 25 July 1564 he succeeded his father Ferdinand I as ruler of the Holy Roman Empire.

Matthias was Holy Roman Emperor from 1612 to 1619, Archduke of Austria from 1608 to 1619, King of Hungary and Croatia from 1608 to 1618, and King of Bohemia from 1611 to 1617. His personal motto was Concordia lumine maior.

Ferdinand II was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia from 1619 until his death in 1637. He was the son of Archduke Charles II of Inner Austria and Maria of Bavaria. His parents were devout Catholics, and, in 1590, they sent him to study at the Jesuits' college in Ingolstadt because they wanted to isolate him from the Lutheran nobles. In July that same year (1590), when Ferdinand was 12 years old, his father died, and he inherited Inner Austria–Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and smaller provinces. His cousin, the childless Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, who was the head of the Habsburg family, appointed regents to administer these lands.

Ladislaus the Posthumous was Duke of Austria and King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia. He was the posthumous son of Albert of Habsburg with Elizabeth of Luxembourg. Albert had bequeathed all his realms to his future son on his deathbed, but only the estates of Austria accepted his last will. Fearing an Ottoman invasion, the majority of the Hungarian lords and prelates offered the crown to Vladislaus III of Poland. The Hussite noblemen and towns of Bohemia did not acknowledge the hereditary right of Albert's descendants to the throne, but also did not elect a new king.

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I, was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several military campaigns, he was elected King of Bohemia in 1469 and adopted the title Duke of Austria in 1487. He was the son of John Hunyadi, Regent of Hungary, who died in 1456. In 1457, Matthias was imprisoned along with his older brother, Ladislaus Hunyadi, on the orders of King Ladislaus the Posthumous. Ladislaus Hunyadi was executed, causing a rebellion that forced King Ladislaus to flee Hungary. After the King died unexpectedly, Matthias's uncle Michael Szilágyi persuaded the Estates to unanimously proclaim the 14-year-old Matthias as king on 24 January 1458. He began his rule under his uncle's guardianship, but he took effective control of government within two weeks.

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as the Danubian monarchy, or Habsburg Empire, was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities that were ruled by the House of Habsburg, especially the dynasty's Austrian branch.

Melchior Khlesl (Klesl,Klesel,Cleselius) was an Austrian statesman and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church during the time of the Counter-Reformation. He was minister-favourite of King and Emperor Matthias and a leading peace-advocate in the period before the Thirty Years War. Klesl was appointed Bishop of Vienna in 1602 and elevated to cardinal in December 1615.

The Kingdom of Bohemia, sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czech Republic. It was an Imperial State in the Holy Roman Empire, and the Bohemian king was a prince-elector of the empire. The kings of Bohemia, besides the region of Bohemia proper itself, also ruled other lands belonging to the Bohemian Crown, which at various times included Moravia, Silesia, Lusatia, and parts of Saxony, Brandenburg, and Bavaria.

The Archduchy of Austria was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire and the nucleus of the Habsburg monarchy. With its capital at Vienna, the archduchy was centered at the Empire's southeastern periphery.

The (Princely) County of Tyrol was an estate of the Holy Roman Empire established about 1140. After 1253, it was ruled by the House of Gorizia and from 1363 by the House of Habsburg. In 1804, the County of Tyrol, unified with the secularised prince-bishoprics of Trent and Brixen, became a crown land of the Austrian Empire. From 1867, it was a Cisleithanian crown land of Austria-Hungary.

The Electorate of Bavaria was an independent hereditary electorate of the Holy Roman Empire from 1623 to 1806, when it was succeeded by the Kingdom of Bavaria.

Austria and Prussia were the most powerful states in the Holy Roman Empire by the 18th and 19th centuries and had engaged in a struggle for supremacy in Germany. The rivalry was characterized by major territorial conflicts and economic, cultural and political aspects. Therefore, the rivalry was an important element of the so called German question in the 19th century.

Vladislaus II, also known as Vladislav, Władysław or Wladislas, was King of Bohemia from 1471 to 1516, and King of Hungary and Croatia from 1490 to 1516. As the eldest son of Casimir IV Jagiellon, he was expected to inherit Poland and Lithuania. George of Poděbrady, the Hussite ruler of Bohemia, offered to make Vladislaus his heir in 1468. George needed Casimir IV's support against the rebellious Catholic noblemen and their ally, Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary. The Diet of Bohemia elected Vladislaus king after George's death, but he could only rule Bohemia proper, because Matthias occupied Moravia, Silesia and both Lusatias. Vladislaus tried to reconquer the four provinces with his father's assistance, but Matthias repelled them.

The Oñate treaty of 29 July 1617 was a secret treaty between the Austrian and Spanish branches of the House of Habsburg.

The siege of Wiener Neustad, part of the Austrian-Hungarian War, was an assault from January 1486 to August 1487 on the Austrian town of Wiener Neustadt. Launched by Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, the 18-month siege ended with the town's surrender and allowed Hungary to take control the of the surrounding Styria and the Lower Austria regions. It was the last of a series of sieges, and followed Hungary's victory in the 1485 Siege of Vienna. The broader war ended less than a year later with an armistice in 1488.

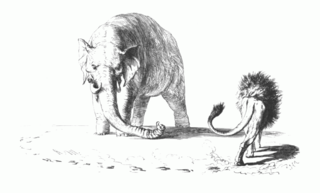

The Austrian–Hungarian War was a military conflict between the Kingdom of Hungary under Mathias Corvinus and the Habsburg Archduchy of Austria under Frederick V. The war lasted from 1477 to 1488 and resulted in significant gains for Matthias, which humiliated Frederick, but which were reversed upon Matthias' sudden death in 1490.

The Margraviate of Moravia was one of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown within the Holy Roman Empire and then Austria-Hungary, existing from 1182 to 1918. It was officially administrated by a margrave in cooperation with a provincial diet. It was variously a de facto independent state, and also subject to the Duchy, later the Kingdom of Bohemia. It comprised the historical region called Moravia, which lies within the present-day Czech Republic.

The War of the Hungarian Succession (1490–1494) was a war of succession triggered by the death of King Matthias Corvinus I of Hungary and Croatia.