The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists, known as the "Boxers" in English due to many of its members having practised Chinese martial arts, which at the time were referred to as "Chinese boxing". It was defeated by the Eight-Nation Alliance of foreign powers.

Outer Manchuria, sometimes called Russian Manchuria, refers to a region in Northeast Asia that is now part of the Russian Far East but historically formed part of Manchuria. While Manchuria now more normatively refers to Northeast China, it originally included areas consisting of Priamurye between the left bank of Amur River and the Stanovoy Range to the north, and Primorskaya which covered the area in the right bank of both Ussuri River and the lower Amur River to the Pacific Coast. The region was ruled by a series of Chinese dynasties and the Mongol Empire, but control of the area was ceded to the Russian Empire by Qing China during the Amur Annexation in the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and 1860 Treaty of Peking, with the terms "Outer Manchuria" and "Russian Manchuria" arising after the Russian annexation.

The China Relief Expedition was an expedition in China undertaken by the United States Armed Forces to rescue United States citizens, European nationals, and other foreign nationals during the latter years of the Boxer Rebellion, which lasted from 1898 to 1901. The China Relief Expedition was part of a multi-national military effort known as the Eight-Nation Alliance to which the United States contributed troops between 1900 and 1901. Towards the close of the expedition, the focus shifted from rescuing non-combatants to suppressing the rebellion. By 1902, at least in the city of Beijing (Peking), the Boxer Rebellion had been effectively controlled.

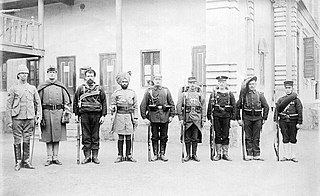

The Eight-Nation Alliance was a multinational military coalition that invaded northern China in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion, with the stated aim of relieving the foreign legations in Beijing, which was being besieged by the popular Boxer militiamen, who were determined to remove foreign imperialism in China. The allied forces consisted of about 45,000 troops from the eight nations of Germany, Japan, Russia, Britain, France, the United States, Italy, and Austria-Hungary. Neither the Chinese nor the quasi-concerted foreign allies issued a formal declaration of war.

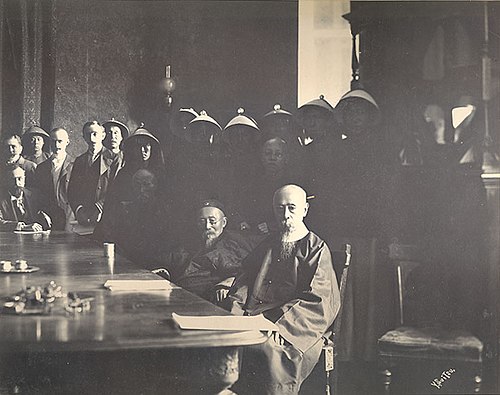

Yikuang, formally known as Prince Qing, was a Manchu noble and politician of the Qing dynasty. He served as the first Prime Minister of the Imperial Cabinet, an office created in May 1911 to replace the Grand Council.

The Zongli Yamen, short for Office for the General Management of Affairs Concerning the Various Countries (總理各國事務衙門), also known as Prime Minister's Office, Office of General Management, was the government body in charge of foreign policy in imperial China during the late Qing dynasty. It was established by Prince Gong on 11 March 1861 after the Convention of Beijing. It was abolished by the Qing government in 1901 and replaced with a Foreign Office of ministry rank.

The Peking Legation Quarter was the area in Beijing (Peking), China where a number of foreign legations were located between 1861 and 1959. In the Chinese language, the area is known as Dong Jiaomin Xiang, which is the name of the hutong through the area. It is located in the Dongcheng District, immediately to the east of Tiananmen Square.

Ronglu, courtesy name Zhonghua, was a Manchu political and military leader of the late Qing dynasty. He was born in the Guwalgiya clan, which was under the Plain White Banner of the Manchu Eight Banners. Deeply favoured by Empress Dowager Cixi, he served in a number of important civil and military positions in the Qing government, including the Zongli Yamen, Grand Council, Grand Secretary, Viceroy of Zhili, Beiyang Trade Minister, Secretary of Defence, Nine Gates Infantry Commander, and Wuwei Corps Commander. He was also the maternal grandfather of Puyi, the last Emperor of China and the Qing dynasty.

The Battle of Peking, or historically the Relief of Peking, was the battle fought on 14–15 August 1900 in Beijing, in which the Eight-Nation Alliance relieved the siege of the Peking Legation Quarter during the Boxer Rebellion. From 20 June 1900, Boxers and Imperial Chinese Army troops had besieged foreign diplomats, citizens and soldiers within the legations of Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Russia, Spain and the United States.

Dong Fuxiang (1839–1908), courtesy name Xingwu (星五), was a Chinese general who lived in the late Qing dynasty. He was born in the Western Chinese province of Gansu. He commanded an army of Hui soldiers, which included the later Ma clique generals Ma Anliang and Ma Fuxiang. According to the Western calendar, his birth date is in 1839.

The Gansu Braves or Gansu Army was a combined army division of 10,000 Chinese Muslim troops from the northwestern province of Kansu (Gansu) in the last decades of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Loyal to the Qing, the Braves were recruited in 1895 to suppress a Muslim revolt in Gansu. Under the command of General Dong Fuxiang (1839–1908), they were transferred to the Beijing metropolitan area in 1898, where they officially became the Rear Division of the Wuwei Corps, a modern army that protected the imperial capital. The Gansu Army included Hui Muslims, Salar Muslims, Dongxiang Muslims, and Bonan Muslims.

The Seymour Expedition was an attempt by a multinational military force led by Admiral Edward Seymour to march to Beijing and relieve the Siege of the Legations from attacks by Qing China government troops and the Boxers in 1900. The Chinese and Boxer fighters defeated the Seymour armies and forced them to return to Tianjin (Tientsin). It was followed later in the summer by the successful Gaselee Expedition.

The siege of the International Legations was a pivotal event during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, in which foreign diplomatic compounds in Peking were besieged by Chinese Boxers and Qing Dynasty troops. The Boxers, fueled by anti-foreign and anti-Christian sentiments, targeted foreigners and Chinese Christians, leading to approximately 900 soldiers, sailors, marines, and civilians from various nations, along with about 2,800 Chinese Christians, seeking refuge in the Legation Quarter. The Qing government, initially ambivalent, ultimately supported the Boxers following international military actions. The siege lasted 55 days, marked by intense combat and a brief truce, until an international relief force arrived from the coast, defeated the Qing forces, and lifted the siege. The failure of the siege and the subsequent occupation of Peking by foreign powers significantly weakened the Boxer Rebellion, leading to its eventual suppression and resulting in increased foreign influence and intervention in China.

The Imperial Decree on events leading to the signing of Boxer Protocol is an imperial decree issued by the government of the Qing dynasty in the name of the Guangxu Emperor, as an official imperial statement on historical events such as Boxer Rebellion, Eight-Nation Alliance and Battle of Peking and Siege of the International Legations, detailing instructions given to Prince Qing and Li Hongzhang as the full representatives of the imperial court in negotiating a peace treaty with the foreign powers, prior to the official signing of the Boxer Protocol on 7 September 1901. This Imperial Decree was officially issued in the name of the Guangxu Emperor and with his official Imperial Seal. The Emperor was actually under house arrest at the time, ordered by Empress Dowager Cixi who held full administrative power.

The Russian invasion of Manchuria or Chinese expedition occurred in the aftermath of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) when concerns regarding Qing China's defeat by the Empire of Japan, and Japan's brief occupation of Liaodong, caused the Russian Empire to speed up their long held designs for imperial expansion across Eurasia.

Xu Jingcheng was a Chinese diplomat and Qing politician supportive of the Hundred Days' Reform. He was envoy to Belgium, France, Italy, Russia, Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany for the Qing imperial court and led reforms in modernizing China's railways and public works. As a modernizer and diplomat, he protested the breaches of international law in 1900 as one of the five ministers executed during the Boxer Rebellion. In Article IIa of the Boxer Protocol of 1901, the Eight-Nation Alliance that had provided military forces successfully pressed for the rehabilitation of Xu Jingcheng by an Imperial Edict of the Qing government:

Imperial Edict of the 13th February last rehabilitated the memories of Hsu Yung-yi, President of the Board of War; Li Shan, President of the Board of Works; Hsu Ching Cheng, Senior VicePresident of the Board of Civil Office; Lien Yuan, Vice-Chancellor of the Grand Council; and Yuan Chang, Vice-President of the Court of Sacrifices, who had been put to death for having protested against the outrageous breaches of international law of last year.

The Mutual Defense Pact of the Southeastern Provinces was an agreement reached in the summer of 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion by Qing dynasty governors of the provinces in southern, eastern and central China when the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded northern China. The governors, including Li Hongzhang, Xu Yingkui, Liu Kunyi, Zhang Zhidong and Yuan Shikai, refused to carry out the imperial decree promulgated by the Qing imperial court to declare war on 11 foreign states, with the aim of preserving peace in their own provinces.

Liang Cheng, courtesy name Liang Chentung, also known as Liang Pi Yuk, and later as Chentung Liang Cheng, was a Chinese ambassador to the United States during the Qing dynasty. He was primarily responsible for negotiating the return payment by the US of its share of the Boxer Indemnity for the establishment of Tsinghua University and the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program.

The Karakhan Manifesto was a statement of Soviet policy toward China dated 25 July 1919. It was issued by Lev Karakhan, deputy commissioner for foreign affairs for Soviet Russia. The manifesto offered to relinquish various rights Russia had obtained by treaty in China, including Chinese territories seized during Tsarism, extraterritoriality, economic concessions, and Russia's share of the Boxer indemnity. These and similar treaties had been denounced by Chinese nationalists as "unequal." The manifesto created a favorable impression of Russia and Marxism among Chinese. It was often contrasted with the Treaty of Versailles (1919), which granted Shandong to Japan.

Baron Adolphe Marie Maurice Joostens, was a Belgian diplomat. As a signatory of the Boxer Protocol, the final act at the Algeciras Conference and the Colonial Charter in which the Congo Free State was ceded to Belgium, Joostens was an important Belgian diplomat in the age of New Imperialism. Throughout his career, Joostens was able to gain the absolute confidence of king Leopold II of Belgium and eventually he became one of the monarch's favourite diplomats.