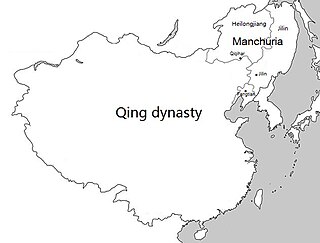

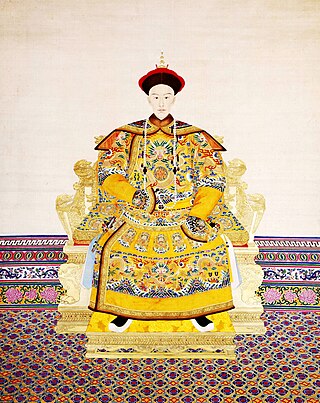

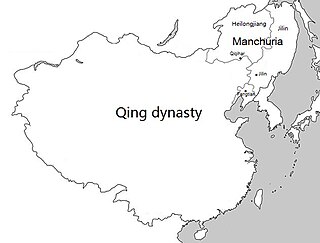

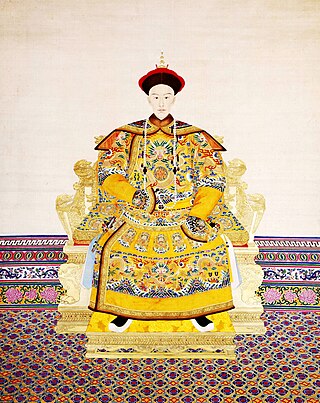

The Qing dynasty, officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China. At its height of power, the empire stretched from the Sea of Japan in the east to the Pamir Mountains in the west, and from the Mongolian Plateau in the north to the South China Sea in the south. Originally emerging from the Later Jin dynasty founded in 1616 and proclaimed in Shenyang in 1636, the dynasty seized control of the Ming capital Beijing and North China in 1644, traditionally considered the start of the dynasty's rule. The dynasty lasted until the Xinhai Revolution of October 1911 led to the abdication of the last emperor in February 1912. The multi-ethnic Qing dynasty assembled the territorial base for modern China. The Qing controlled the most territory of any dynasty in Chinese history, and in 1790 represented the fourth-largest empire in world history to that point. With over 426 million citizens in 1907, it was the most populous country in the world at the time.

Manchuria is a term that refers to a region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China, and historically parts of the modern-day Russian Far East, often referred to as Outer Manchuria. Its definition may refer to varying geographical extents as follows: in the narrow sense, the area constituted by three Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning but broadly also including the eastern Inner Mongolian prefectures of Hulunbuir, Hinggan, Tongliao, and Chifeng, collectively known as Northeast China; in a broader sense, the area of historical Manchuria includes the aforementioned regions plus the Amur river basin, parts of which were ceded to the Russian Empire by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty during the Amur Annexation of 1858–1860. The parts of Manchuria ceded to Russia are collectively known as Outer Manchuria or Russian Manchuria, which include present-day Amur Oblast, Primorsky Krai, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, the southern part of Khabarovsk Krai, and the eastern edge of Zabaykalsky Krai.

China proper, also called Inner China, are terms used primarily in the West in reference to the traditional "core" regions of China centered in the southeast. The term was first used by Westerners during the Manchu-led Qing dynasty to describe the distinction between the historical "Han lands" (漢地)—i.e. regions long dominated by the majority Han population—and the "frontier" regions of China where more non-Han ethnic groups and new foreign immigrants reside, sometimes known as "Outer China". There is no fixed extent for China proper, as many administrative, cultural, and linguistic shifts have occurred in Chinese history. One definition refers to the original area of Chinese civilization, the Central Plain ; another to the Eighteen Provinces of the Qing dynasty. There was no direct translation for "China proper" in the Chinese language at the time due to differences in terminology used by the Qing to refer to the regions. Even to today, the expression is controversial among scholars, particularly in mainland China, due to issues pertaining to contemporary territorial claim and ethnic politics.

The Manchus are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Qing (1636–1912) dynasties of China were established and ruled by the Manchus, who are descended from the Jurchen people who earlier established the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in northern China.

Han nationalism is a form of ethnic nationalism asserting ethnically Han Chinese as the exclusive constituents of the Chinese nation. It is often in dialogue with other conceptions of Chinese nationalism, often mutually-exclusive or otherwise contradictory ones. Han Chinese are the dominant ethnic group in both states claiming to represent the Chinese nation: the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China.

The Eight Banners were administrative and military divisions under the Later Jin and Qing dynasties of China into which all Manchu households were placed. In war, the Eight Banners functioned as armies, but the banner system was also the basic organizational framework of all of Manchu society. Created in the early 17th century by Nurhaci, the banner armies played an instrumental role in his unification of the fragmented Jurchen people and in the Qing dynasty's conquest of the Ming dynasty.

Pamela Kyle Crossley is a historian of modern China, northern Asia, and global history and is the Charles and Elfriede Collis Professor of History, Dartmouth College. She is a founding appointment of the Dartmouth Society of Fellows.

Mongolia under Qing rule was the rule of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China over the Mongolian Plateau, including the four Outer Mongolian aimags and the six Inner Mongolian aimags from the 17th century to the end of the dynasty. The term "Mongolia" is used here in the broader historical sense, and includes an area much larger than the modern-day state of Mongolia. By the early 1630s Ligdan Khan saw much of his power weakened due to the disunity of the Mongol tribes. He was subsequently defeated by the Later Jin dynasty and died soon afterwards. His son Ejei handed the Yuan imperial seal over to Hong Taiji in 1635, thus ending the rule of the Northern Yuan dynasty in Inner Mongolia. However, the Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia continued to rule until they were overrun by the Dzungar Khanate in 1690, and they submitted to the Qing dynasty in 1691.

De-Sinicization is a process of eliminating or reducing Han Chinese cultural elements, identity, or consciousness from a society or nation. In modern contexts, it is often contrasted with the assimilation process of Sinicization.

A conquest dynasty in the history of China refers to a Chinese dynasty established by non-Han ethnicities which ruled parts or all of China proper, the traditional heartland of the Han people, and whose rulers may or may not have fully assimilated into the dominant Han culture. Four major dynasties have been considered "conquest dynasties": the Liao (916–1125), the Jin (1115–1234), Yuan (1271–1368), and Qing (1644–1912).

The Khorchin are a subgroup of the Mongols that speak the Khorchin dialect of Mongolian and predominantly live in northeastern Inner Mongolia of China.

Zhonghua minzu is a political term in modern Chinese nationalism related to the concepts of nation-building, ethnicity, and race in the Chinese nationality.

Mark C. Elliott is the Mark Schwartz Professor of Chinese and Inner Asian History at Harvard University, where he is Vice Provost for International Affairs. He is also a seminal figure of the school called the New Qing History.

The history of the Qing dynasty began in the first half of the 17th century, when the Qing dynasty was established and became the last imperial dynasty of China, succeeding the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The Manchu leader Hong Taiji renamed the Later Jin established by his father Nurhaci to "Great Qing" in 1636, sometimes referred to as the Predynastic Qing in historiography. By 1644 the Shunzhi Emperor and his prince regent seized control of the Ming capital Beijing, and the year 1644 is generally considered the start of the dynasty's rule. The Qing dynasty lasted until 1912, when Puyi abdicated the throne in response to the 1911 Revolution. As the final imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty reached heights of power unlike any of the Chinese dynasties which preceded it, engaging in large-scale territorial expansion which ended with embarrassing defeat and humiliation to the foreign powers whom they believe to be inferior to them. The Qing dynasty's inability to successfully counter Western and Japanese imperialism ultimately led to its downfall, and the instability which emerged in China during the final years of the dynasty ultimately paved the way for the Warlord Era.

The New Qing History is a historiographical school that gained prominence in the United States in the mid-1990s by offering a major revision of history of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China.

The Qing dynasty was an imperial Chinese dynasty ruled by the Aisin Gioro clan of Manchu ethnicity. Officially known as the Great Qing, the dynastic empire was also widely known in English as China and the Chinese Empire both during its existence, especially internationally, and after the fall of the dynasty.

The Qing dynasty in Inner Asia was the expansion of the Qing dynasty's realm in Inner Asia in the 17th and the 18th century AD, including both Inner Mongolia and Outer Mongolia, both Manchuria and Outer Manchuria, Tibet, Qinghai and Xinjiang.

Manchuria under Qing rule was the rule of the Qing dynasty of China over the greater region of Manchuria, including today's Northeast China and Outer Manchuria, although Outer Manchuria was lost to the Russian Empire after the Amur Annexation. The Qing dynasty itself was established by the Manchus, a Tungusic people from Manchuria, who later replaced the Ming dynasty as the ruling dynasty of China. Thus, the region is often seen to have had a special status during the Qing and was not governed as regular provinces until the late Qing dynasty, although the name "Manchuria" itself is an exonym of Japanese origin and was not used by the Qing dynasty in Chinese or Manchu.

The Sinicization of the Manchus was the process in which the Manchu people became assimilated into the Han-dominated Chinese society. It occurred most prominently during the Qing dynasty when the new Manchu rulers actively attempted to assimilate themselves and their people with the Han to increase the legitimacy of the new dynasty. As a result, when the Qing dynasty fell, many Manchu had already adopted Han Chinese customs, languages and surnames. For example, some descendants of the ruling imperial House of Aisin-Gioro adopted the Han Chinese surname Jin as both Jin and Aisin mean gold.

The debate on the "Chineseness" of the Yuan and Qing dynasties is concerned with whether the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1912) can be considered "Chinese dynasties", and whether they were representative of "China" during their respective historical periods. The debate, although historiographical in nature, has political implications. Mainstream academia and successive governments of China, including the imperial governments of the Yuan and Qing dynasties, have maintained the view that they were "Chinese" and representative of "China". The debate stemmed from differing opinions on whether regimes founded by ethnic minorities could be representative of "China", where the Han Chinese were and remain the main people.