Related Research Articles

The Qing dynasty, officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speaking ethnic group who unified other Jurchen tribes to form a new "Manchu" ethnic identity. The dynasty was officially proclaimed in 1636 in Manchuria. It seized control of Beijing in 1644, then later expanded its rule over the whole of China proper and Taiwan, and finally expanded into Inner Asia. The dynasty lasted until 1912 when it was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution. In orthodox Chinese historiography, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China. The multiethnic Qing empire lasted for almost three centuries and assembled the territorial base for modern China. It was the largest imperial dynasty in the history of China and in 1790 the fourth-largest empire in world history in terms of territorial size. With 419,264,000 citizens in 1907, it was the world's most populous country at the time.

The Manchus are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Qing (1636–1912) dynasties of China were established and ruled by the Manchus, who are descended from the Jurchen people who earlier established the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in northern China.

The Eight Banners were administrative and military divisions under the Later Jin and Qing dynasties of China into which all Manchu households were placed. In war, the Eight Banners functioned as armies, but the banner system was also the basic organizational framework of all of Manchu society. Created in the early 17th century by Nurhaci, the banner armies played an instrumental role in his unification of the fragmented Jurchen people and in the Qing dynasty's conquest of the Ming dynasty.

The Shunzhi Emperor was the second emperor of the Qing dynasty of China, and the first Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1644 to 1661. A committee of Manchu princes chose him to succeed his father, Hong Taiji (1592–1643), in September 1643, when he was five years old. The princes also appointed two co-regents: Dorgon (1612–1650), the 14th son of the Qing dynasty's founder Nurhaci (1559–1626), and Jirgalang (1599–1655), one of Nurhaci's nephews, both of whom were members of the Qing imperial clan.

Pamela K Crossley is a historian of modern China, northern Asia, and global history and is the Charles and Elfriede Collis Professor of History, Dartmouth College. She is a founding appointment of the Dartmouth Society of Fellows.

The Plain Yellow Banner was one of the Eight Banners of Manchu military and society during the Later Jin and Qing dynasty of China. The Plain Yellow Banner was one of three "upper" banner armies under the direct command of the emperor himself, and one of the four "right wing" banners. The Plain Yellow Banner was the original banner commanded personally by Nurhaci. The Plain Yellow Banner and the Bordered Yellow Banner were split from each other in 1615, when the troops of the original four banner armies were divided into eight by adding a bordered variant to each banner's design. After Nurhaci's death, his son Hong Taiji became khan, and took control of both yellow banners. Later, the Shunzhi Emperor took over the Plain White Banner after the death of his regent, Dorgon, to whom it previously belonged. From that point forward, the emperor directly controlled three "upper" banners, as opposed to the other five "lower" banners.

De-Sinicization refers to a process of eliminating or reducing Chinese cultural elements, identity, or consciousness from a society or nation. In modern contexts, it is often used in tandem with decolonization and contrasted to the assimilation process of Sinicization.

The Imperial Household Department was an institution of the Qing dynasty of China. Its primary purpose was to manage the internal affairs of the Qing imperial family and the activities of the inner palace, but it also played an important role in Qing relations with Tibet and Mongolia, engaged in trading activities, managed textile factories in the Jiangnan region, and even published books.

Ping-ti Ho or Bingdi He, who also wrote under the name P.T. Ho, was a Chinese-American historian. He wrote widely on China's history, including works on demography, plant history, ancient archaeology, and contemporary events. He taught at University of Chicago for most of his career, and was President of the Association for Asian Studies in 1975, the first scholar of Asian descent to have that honor.

Mark C. Elliott is the Mark Schwartz Professor of Chinese and Inner Asian History at Harvard University, where he is Vice Provost for International Affairs. He is also one of the scholars who form part of the school called the New Qing History.

The Imperial Clan Court or Court of the Imperial Clan was an institution responsible for all matters pertaining to the imperial family under the Ming and Qing dynasties of imperial China. This institution also existed under the Nguyễn dynasty of Vietnam where it managed matters pertaining to the Nguyễn Phúc clan.

Shamanism was the dominant religion of the Jurchen people of northeast Asia and of their descendants, the Manchu people. As early as the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), the Jurchens conducted shamanic ceremonies at shrines called tangse. There were two kinds of shamans: those who entered in a trance and let themselves be possessed by the spirits, and those who conducted regular sacrifices to heaven, to a clan's ancestors, or to the clan's protective spirits.

Manchu became a literary language after the creation of the Manchu script in 1599. Romance of the Three Kingdoms was translated by Dahai. Dahai translated Wanbao quanshu 萬寶全書.

Identity in China was strongly dependent on the Eight Banner system prior to and during the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1912). China consisted of multiple ethnic groups, of which the Han, Mongols and Manchus participated in the banner system. Identity, however, was defined much more by culture, language and participation in the military until the Qianlong Emperor resurrected the ethnic classifications.

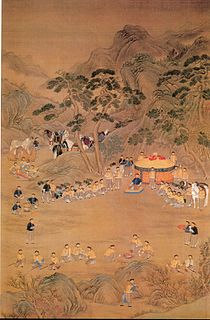

The imperial hunt of the Qing dynasty was an annual rite of the emperors of China during the Qing dynasty (1636–1912). It was first organized in 1681 by the Kangxi Emperor at the imperial hunting grounds at Mulan (modern-day Weichang Manchu and Mongol Autonomous County, near what would become the summer residence of the Qing emperors at Chengde. Starting in 1683 the event was held annually at Mulan during the autumn, lasting up to a month. The Qing dynasty hunt was a synthesis of earlier Chinese and Inner Asian hunting traditions, particularly those of the Manchus and Mongols. The emperor himself participated in the hunt, along with thousands of soldiers, imperial family members, and government officials.

The New Qing History is a historiographical school that gained prominence in the United States in the mid-1990s by offering a wide-ranging revision of history of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China. Orthodox historians tend to emphasize the power of the Han people to "sinicize" their conquerors in their thought and institutions. In the 1980s and early 1990s, American scholars began to learn Manchu and took advantage of newly opened Chinese- and Manchu-language archives. This research found that the Manchu rulers were savvy in manipulating their subjects and from the 1630s through at least the 18th century, emperors developed a sense of Manchu identity and used traditional Han Chinese culture and Confucian models to rule, while blending with models from other ethnic groups across the vast empire, including those from northern China, the Eurasian Steppe, Inner Asia, and Central Asia. According to some scholars, at the height of their power, the Qing regarded the Han Chinese as only a part, although a very important part, of a much wider empire that extended into the Inner Asian territories of Mongolia, Tibet, Manchuria and Xinjiang.

The Sinicization of the Manchus is the process in which the Manchu people became assimilated into the Han-dominated Chinese society. It had occurred most prominently during the Qing dynasty when attempts were made by the new Manchu rulers of China to assimilate themselves and their people with the Han under the new dynasty to increase its legitimacy.

Events from the year 1670 in China.

Beatrice S. Bartlett or Betsy Bartlett is an American historian of modern Chinese history, from the 1600s to the present. She is Professor Emeritus of History at Yale University.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Department of History (2015).

- ↑ AAS Board of Directors and Officers

- ↑ MSG Interview: Evelyn Rawski

- ↑ ScanlonCosner (1996), pp. 184–186.

- ↑ Cohen, Paul (1984). Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese Past. New York, London: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52546-6., p. 173–175

- ↑ Rawski (1996).

- ↑ Pamela Crossley, Beyond the culture: my comments on New Qing history

- ↑ Leonard, Jane Kate (2000), "Review", China Review International, 7: 200

Sources

- Department of History (2015), Curriculum vitae Evelyn Rawski, archived from the original on 2015-02-26, retrieved 2015-02-26

- Scanlon, Jennifer; Cosner, Sharon (1996). "Rawski, Evelyn". American Women Historians, 1700s-1900s: A Biographical Dictionary. pp. 184–186. ISBN 978-0-313-29664-2.