Lymphoma is a group of blood and lymph tumors that develop from lymphocytes. The name typically refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include enlarged lymph nodes, fever, drenching sweats, unintended weight loss, itching, and constantly feeling tired. The enlarged lymph nodes are usually painless. The sweats are most common at night.

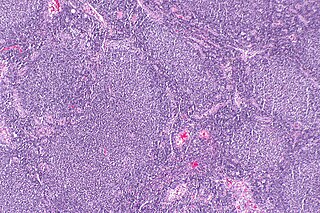

Burkitt lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system, particularly B lymphocytes found in the germinal center. It is named after Denis Parsons Burkitt, the Irish surgeon who first described the disease in 1958 while working in equatorial Africa. It is a highly aggressive form of cancer which often, but not always, manifests after a person develops acquired immunodeficiency from infection with Epstein-Barr Virus or Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

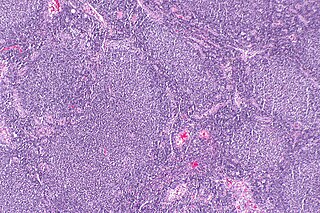

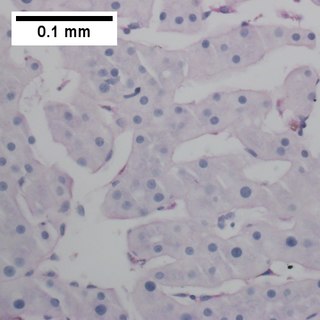

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a cancer that involves certain types of white blood cells known as lymphocytes. The cancer originates from the uncontrolled division of specific types of B-cells known as centrocytes and centroblasts. These cells normally occupy the follicles in the germinal centers of lymphoid tissues such as lymph nodes. The cancerous cells in FL typically form follicular or follicle-like structures in the tissues they invade. These structures are usually the dominant histological feature of this cancer.

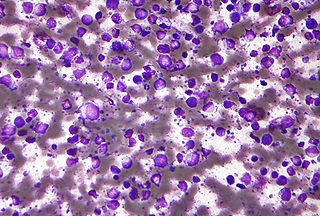

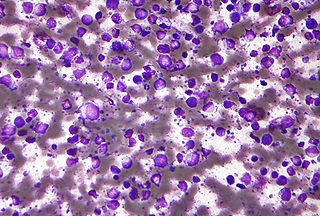

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is classified as a diffuse large B cell lymphoma. It is a rare malignancy of plasmablastic cells that occurs in individuals that are infected with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Plasmablasts are immature plasma cells, i.e. lymphocytes of the B-cell type that have differentiated into plasmablasts but because of their malignant nature do not differentiate into mature plasma cells but rather proliferate excessively and thereby cause life-threatening disease. In PEL, the proliferating plasmablastoid cells commonly accumulate within body cavities to produce effusions, primarily in the pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal cavities, without forming a contiguous tumor mass. In rare cases of these cavitary forms of PEL, the effusions develop in joints, the epidural space surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and underneath the capsule which forms around breast implants. Less frequently, individuals present with extracavitary primary effusion lymphomas, i.e., solid tumor masses not accompanied by effusions. The extracavitary tumors may develop in lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, the gastrointestinal tract, skin, spleen, liver, lungs, central nervous system, testes, paranasal sinuses, muscle, and, rarely, inside the vasculature and sinuses of lymph nodes. As their disease progresses, however, individuals with the classical effusion-form of PEL may develop extracavitary tumors and individuals with extracavitary PEL may develop cavitary effusions.

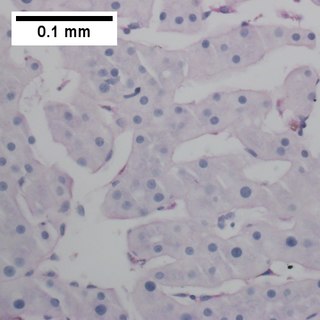

Intravascular lymphomas (IVL) are rare cancers in which malignant lymphocytes proliferate and accumulate within blood vessels. Almost all other types of lymphoma involve the proliferation and accumulation of malignant lymphocytes in lymph nodes, other parts of the lymphatic system, and various non-lymphatic organs but not in blood vessels.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a cancer of B cells, a type of lymphocyte that is responsible for producing antibodies. It is the most common form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among adults, with an annual incidence of 7–8 cases per 100,000 people per year in the US and UK. This cancer occurs primarily in older individuals, with a median age of diagnosis at ~70 years, although it can occur in young adults and, in rare cases, children. DLBCL can arise in virtually any part of the body and, depending on various factors, is often a very aggressive malignancy. The first sign of this illness is typically the observation of a rapidly growing mass or tissue infiltration that is sometimes associated with systemic B symptoms, e.g. fever, weight loss, and night sweats.

Aggressive NK-cell leukemia is a disease with an aggressive, systemic proliferation of natural killer cells and a rapidly declining clinical course.

Richter's transformation (RT), also known as Richter's syndrome, is the conversion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or its variant, small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), into a new and more aggressively malignant disease. CLL is the circulation of malignant B lymphocytes with or without the infiltration of these cells into lymphatic or other tissues while SLL is the infiltration of these malignant B lymphocytes into lymphatic and/or other tissues with little or no circulation of these cells in the blood. CLL along with its SLL variant are grouped together in the term CLL/SLL.

Aggressive lymphoma, also known as high-grade lymphoma, is a group of fast growing non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) is a rare hematologic malignancy. It was initially regarded as a form of lymphocyte-derived cutaneous lymphoma and alternatively named CD4+CD56+ hematodermic tumor, blastic NK cell lymphoma, and agranular CD4+ NK cell leukemia. Later, however, the disease was determined to be a malignancy of plasmacytoid dendritic cells rather than lymphocytes and therefore termed blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. In 2016, the World Health Organization designated BPDCN to be in its own separate category within the myeloid class of neoplasms. It is estimated that BPDCN constitutes 0.44% of all hematological malignancies.

Marginal zone lymphomas, also known as marginal zone B-cell lymphomas (MZLs), are a heterogeneous group of lymphomas that derive from the malignant transformation of marginal zone B-cells. Marginal zone B cells are innate lymphoid cells that normally function by rapidly mounting IgM antibody immune responses to antigens such as those presented by infectious agents and damaged tissues. They are lymphocytes of the B-cell line that originate and mature in secondary lymphoid follicles and then move to the marginal zones of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, the spleen, or lymph nodes. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue is a diffuse system of small concentrations of lymphoid tissue found in various submucosal membrane sites of the body such as the gastrointestinal tract, mouth, nasal cavity, pharynx, thyroid gland, breast, lung, salivary glands, eye, skin and the human spleen.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTCL-NT) is a rare type of lymphoma that commonly involves midline areas of the nasal cavity, oral cavity, and/or pharynx At these sites, the disease often takes the form of massive, necrotic, and extremely disfiguring lesions. However, ENKTCL-NT can also involve the eye, larynx, lung, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and various other tissues. ENKTCL-NT mainly affects adults; it is relatively common in Asia and to lesser extents Mexico, Central America, and South America but is rare in Europe and North America. In Korea, ENKTCL-NT often involves the skin and is reported to be the most common form of cutaneous lymphoma after mycosis fungoides.

Gene expression profiling has revealed that diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is composed of at least 3 different sub-groups, each having distinct oncogenic mechanisms that respond to therapies in different ways. Germinal Center B-Cell like (GCB) DLBCLs appear to arise from normal germinal center B cells, while Activated B-cell like (ABC) DLBCLs are thought to arise from postgerminal center B cells that are arrested during plasmacytic differentiation. The differences in gene expression between GCB DLBCL and ABC DLBCL are as vast as the differences between distinct types of leukemia, but these conditions have historically been grouped together and treated as the same disease.

Large B-cell lymphoma arising in HHV8-associated multicentric Castleman's disease is a type of large B-cell lymphoma, recognized in the WHO 2008 classification. It is sometimes called the plasmablastic form of multicentric Castleman disease. It has sometimes been confused with plasmablastic lymphoma in the literature, although that is a dissimilar specific entity. It has variable CD20 expression and unmutated immunoglobulin variable region genes.

Epstein–Barr virus positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified is a form of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) accounting for around 10-15% of DLBCL cases. DLBCL are lymphomas in which B-cell lymphocytes proliferate excessively, invade multiple tissues, and often causes life-threatening tissue damage. EBV+ DLBCL is distinguished from DLBCL in that virtually all the large B cells in the tissue, infiltrates of the Epstien-Barr virus (EBV) express EBV genes characteristic of the virus's latency III or II phase. EBV is a ubiquitous virus, infecting around 95% of the world population.

Epstein–Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative diseases are a group of disorders in which one or more types of lymphoid cells, i.e. B cells, T cells, NK cells, and histiocytic-dendritic cells, are infected with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). This causes the infected cells to divide excessively, and is associated with the development of various non-cancerous, pre-cancerous, and cancerous lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). These LPDs include the well-known disorder occurring during the initial infection with the EBV, infectious mononucleosis, and the large number of subsequent disorders that may occur thereafter. The virus is usually involved in the development and/or progression of these LPDs although in some cases it may be an "innocent" bystander, i.e. present in, but not contributing to, the disease.

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBCL-LT) is a cutaneous lymphoma skin disease that occurs mostly in elderly females. In this disease, B cells become malignant, accumulate in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue below the dermis to form red and violaceous skin nodules and tumors. These lesions typically occur on the lower extremities but in uncommon cases may develop on the skin at virtually any other site. In ~10% of cases, the disease presents with one or more skin lesions none of which are on the lower extremities; the disease in these cases is sometimes regarded as a variant of PCDLBL, LT termed primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other (PCDLBC-O). PCDLBCL, LT is a subtype of the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) and has been thought of as a cutaneous counterpart to them. Like most variants and subtypes of the DLBCL, PCDLBCL, LT is an aggressive malignancy. It has a 5-year overall survival rate of 40–55%, although the PCDLBCL-O variant has a better prognosis than cases in which the legs are involved.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation (DLBCL-CI) is a subtype of the Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and a rare form of the Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative diseases, i.e. conditions in which lymphocytes infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) proliferate excessively in one or more tissues. EBV infects ~95% of the world's population to cause no symptoms, minor non-specific symptoms, or infectious mononucleosis. The virus then enters a latency phase in which the infected individual becomes a lifetime asymptomatic carrier of the virus. Some weeks, months, years, or decades thereafter, a very small fraction of these carriers, particularly those with an immunodeficiency, develop any one of various EBV-associated benign or malignant diseases.

Fibrin-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (FA-DLBCL) is an extremely rare form of the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL). DLBCL are lymphomas in which a particular type of lymphocyte, the B-cell, proliferates excessively, invades multiple tissues, and often causes life-threatening tissue damage. DLBCL have various forms as exemplified by one of its subtypes, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation (DLBCL-CI). DLBCL-CI is an aggressive malignancy that develops in sites of chronic inflammation that are walled off from the immune system. In this protected environment, the B-cells proliferate excessively, acquire malignant gene changes, form tumor masses, and often spread outside of the protected environment. In 2016, the World Health Organization provisionally classified FA-DLBCL as a DLBCL-CI. Similar to DLBCL-CI, FA-DLBCL involves the proliferation of EBV-infected large B-cells in restricted anatomical spaces that afford protection from an individual's immune system. However, FA-DLBCL differs from DLBCL-CI in many other ways, including, most importantly, its comparatively benign nature. Some researchers have suggested that this disease should be regarded as a non-malignant or pre-malignant lymphoproliferative disorder rather than a malignant DLBCL-CI.

Lymphoid neoplasms with plasmablastic differentiation were classified by the World Health Organization, 2017 as a sub-grouping of several distinct but rare lymphomas in which the malignant cells are B-cell lymphocytes that have become plasmablasts, i.e. immature plasma cells. Normally, B-cells take up foreign antigens, move to the germinal centers of secondary lymphoid organs such the spleen and lymph nodes, and at these sites are stimulated by T-cell lymphocytes to differentiate into plasmablasts and thereafter mature plasma cells. Plasmablasts, and to a greater extent, plasma cells make and secrete antibodies that bind the antigens to which their predecessor B-cells were previously exposed. Antibodies function, in part, to neutralize harmful bacteria and viruses by binding antigens that are exposed on their surfaces. Due to their malignant nature, however, the plasmablasts in lymphoid neoplasms with plasmablastic differentiation do not mature into plasma cells or form antibodies but rather uncontrollably proliferate in and damage various tissues and organs. The individual lymphomas in this sub-group of malignancies have heterogeneous clinical, morphological, and gene findings that often overlap with other members of the sub-group. In consequence, correctly diagnosing these lymphomas has been challenging. Nonetheless, it is particularly important to diagnose them correctly because they often have very different prognoses and treatments. The lymphoid neoplasms with plasmacytic differentiation are: