In psychology, fantasy is a broad range of mental experiences, mediated by the faculty of imagination in the human brain, and marked by an expression of certain desires through vivid mental imagery. Fantasies are generally associated with scenarios that are impossible.

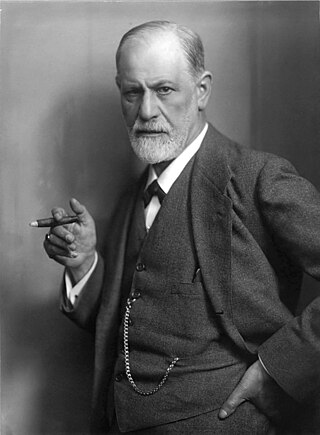

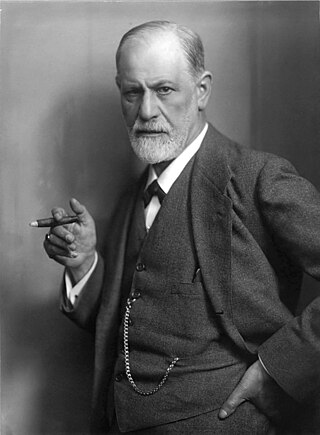

Psychoanalysis is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques that deal in part with the unconscious mind, and which together form a method of treatment for mental disorders. The discipline was established in the early 1890s by Sigmund Freud, whose work stemmed partly from the clinical work of Josef Breuer and others. Freud developed and refined the theory and practice of psychoanalysis until his death in 1939. In an encyclopedia article, he identified the cornerstones of psychoanalysis as "the assumption that there are unconscious mental processes, the recognition of the theory of repression and resistance, the appreciation of the importance of sexuality and of the Oedipus complex." Freud's students Alfred Adler and Carl Gustav Jung developed offshoots of psychoanalysis which they called individual psychology (Adler) and Analytical Psychology (Jung), although Freud himself wrote a number of criticisms of them and emphatically denied that they were forms of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis was later developed in different directions by neo-Freudian thinkers, such as Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan.

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in the psyche, through dialogue between patient and psychoanalyst, and the distinctive theory of mind and human agency derived from it.

In psychoanalytic theory, the id, ego, and super-ego are three distinct, interacting agents in the psychic apparatus, defined in Sigmund Freud's structural model of the psyche. The three agents are theoretical constructs that Freud employed to describe the basic structure of mental life as it was encountered in psychoanalytic practice. Freud himself used the German terms das Es, Ich, and Über-Ich, which literally translate as "the it", "I", and "over-I". The Latin terms id, ego and super-ego were chosen by his original translators and have remained in use.

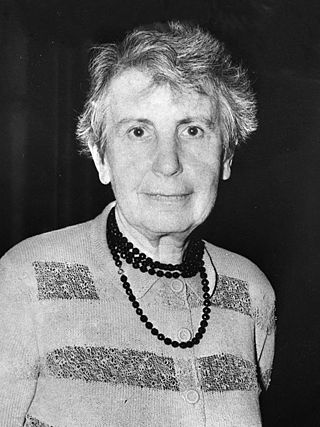

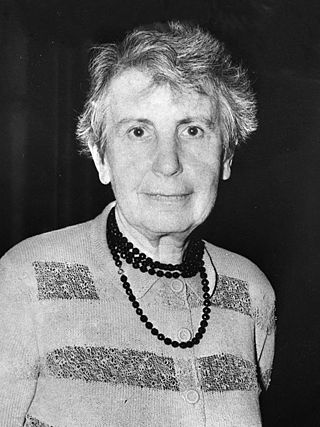

Anna Freud CBE was a British psychoanalyst of Austrian-Jewish descent. She was born in Vienna, the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. She followed the path of her father and contributed to the field of psychoanalysis. Alongside Hermine Hug-Hellmuth and Melanie Klein, she may be considered the founder of psychoanalytic child psychology.

Emma Eckstein (1865–1924) was an Austrian author. She was "one of Sigmund Freud's most important patients and, for a short period of time around 1897, became a psychoanalyst herself". She has been described as "the first woman analyst", who became "both colleague and patient" for Freud. As analyst, while "working mainly in the area of sexual and social hygiene, she also explored how 'daydreams, those "parasitic plants", invaded the life of young girls'."

The genital stage in psychoanalysis is the term used by Sigmund Freud to describe the final stage of human psychosexual development. The individual develops a strong sexual interest in people outside of the family.

In psychology and psychiatry, scopophilia or scoptophilia is an aesthetic pleasure drawn from looking at an object or a person. In human sexuality, the term scoptophilia describes the sexual pleasure that a person derives from looking at prurient objects of eroticism, such as pornography, the nude body, and fetishes, as a substitute for actual participation in a sexual relationship.

In Freudian psychology, psychosexual development is a central element of the psychoanalytic sexual drive theory. Freud believed that personality developed through a series of childhood stages in which pleasure seeking energies from the child became focused on certain erogenous areas. An erogenous zone is characterized as an area of the body that is particularly sensitive to stimulation. The five psychosexual stages are the oral, the anal, the phallic, the latent, and the genital. The erogenous zone associated with each stage serves as a source of pleasure. Being unsatisfied at any particular stage can result in fixation. On the other hand, being satisfied can result in a healthy personality. Sigmund Freud proposed that if the child experienced frustration at any of the psychosexual developmental stages, they would experience anxiety that would persist into adulthood as a neurosis, a functional mental disorder.

Repression is a key concept of psychoanalysis, where it is understood as a defence mechanism that "ensures that what is unacceptable to the conscious mind, and would if recalled arouse anxiety, is prevented from entering into it." According to psychoanalytic theory, repression plays a major role in many mental illnesses, and in the psyche of the average person.

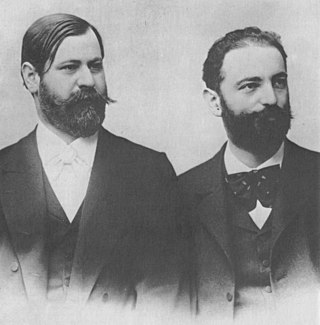

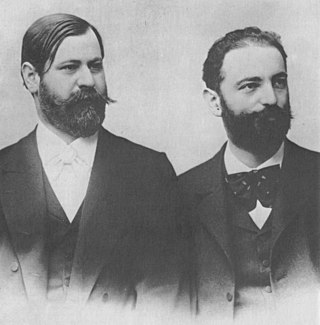

Wilhelm Fliess was a German otolaryngologist who practised in Berlin. He developed the pseudoscientific theory of human biorhythms and a possible nasogenital connection that have not been accepted by modern scientists. He is today best remembered for his close friendship and theoretical collaboration with Sigmund Freud, a controversial chapter in the history of psychoanalysis.

Karl Abraham was an influential German psychoanalyst, and a collaborator of Sigmund Freud, who called him his 'best pupil'.

Wilhelm Stekel was an Austrian physician and psychologist, who became one of Sigmund Freud's earliest followers, and was once described as "Freud's most distinguished pupil". According to Ernest Jones, "Stekel may be accorded the honour, together with Freud, of having founded the first psycho-analytic society.". However, a phrase used by Freud in a letter to Stekel, "the Psychological Society founded by you," suggests that the initiative was entirely Stekel's. Jones also wrote of Stekel that he was "a naturally gifted psychologist with an unusual flair for detecting repressed material." Freud and Stekel later had a falling-out, with Freud announcing in November 1912 that "Stekel is going his own way". A letter from Freud to Stekel dated January 1924 indicates that the falling out was on interpersonal rather than theoretical grounds, and that at some point Freud developed a low opinion of his former associate. He wrote: "I...contradict your often repeated assertion that you were rejected by me on account of scientific differences. This sounds quite good in public but it doesn't correspond with the truth. It was exclusively your personal qualities - usually described as character and behavior - which made collaboration with you impossible for my friends and myself." Stekel's works are translated and published in many languages.

Otto Fenichel was a psychoanalyst of the so-called "second generation".

Love and hate as co-existing forces have been thoroughly explored within the literature of psychoanalysis, building on awareness of their co-existence in Western culture reaching back to the “odi et amo” of Catullus, and Plato's Symposium.

Freud's seduction theory was a hypothesis posited in the mid-1890s by Sigmund Freud that he believed provided the solution to the problem of the origins of hysteria and obsessional neurosis. According to the theory, a repressed memory of an early childhood sexual abuse or molestation experience was the essential precondition for hysterical or obsessional symptoms, with the addition of an active sexual experience up to the age of eight for the latter.

Fixation is a concept that was originated by Sigmund Freud (1905) to denote the persistence of anachronistic sexual traits. The term subsequently came to denote object relationships with attachments to people or things in general persisting from childhood into adult life.

In neo-Freudian psychology, the Electra complex, as proposed by Carl Jung in his Theory of Psychoanalysis, is a girl's psychosexual competition with her mother for possession of her father. In the course of her psychosexual development, the complex is the girl's phallic stage; a boy's analogous experience is the Oedipus complex. The Electra complex occurs in the third—phallic stage —of five psychosexual development stages: the oral, the anal, the phallic, the latent, and the genital—in which the source of libido pleasure is in a different erogenous zone of the infant's body.

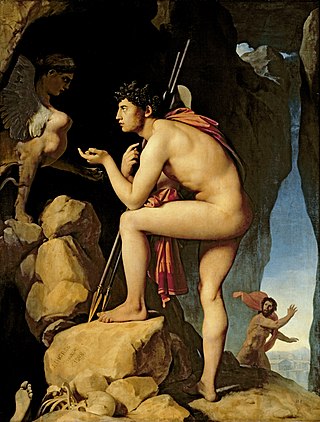

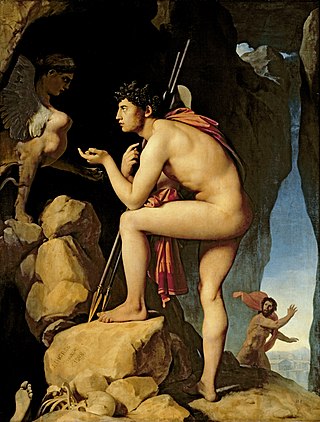

The Oedipus complex is an idea in psychoanalytic theory. The complex is an ostensibly universal phase in the life of a young boy in which, to try to immediately satisfy basic desires, he unconsciously wishes to have sex with his mother and disdains his father for having sex and being satisfied before him. Sigmund Freud introduced the idea in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), and coined the term in his paper A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men (1910).

Counterphobic attitude is a response to anxiety that, instead of fleeing the source of fear in the manner of a phobia, actively seeks it out, in the hope of overcoming the original anxiousness.