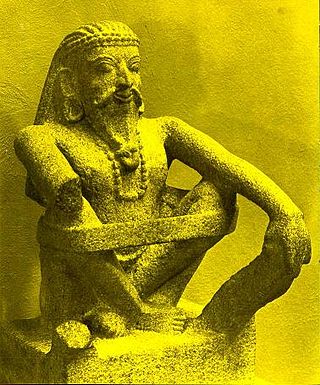

Yoga is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciousness untouched by the mind (Chitta) and mundane suffering (Duḥkha). There is a wide variety of schools of yoga, practices, and goals in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, and traditional and modern yoga is practiced worldwide.

Maya, literally "illusion" or "magic", has multiple meanings in Indian philosophies depending on the context. In later Vedic texts, māyā connotes a "magic show, an illusion where things appear to be present but are not what they seem"; the principle which shows "attributeless Absolute" as having "attributes". Māyā also connotes that which "is constantly changing and thus is spiritually unreal", and therefore "conceals the true character of spiritual reality".

Ātman is a Sanskrit word for the true or eternal Self or the self-existent essence or impersonal witness-consciousness within each individual. Atman is conceptually different from Jīvātman, which persists across multiple bodies and lifetimes. Some schools of Indian philosophy regard the Ātman as distinct from the material or mortal ego (Ahamkara), the emotional aspect of the mind (Citta), and existence in an embodied form (Prakṛti). The term is often translated as soul, but is better translated as "Self", as it solely refers to pure consciousness or witness-consciousness, beyond identification with phenomena. In order to attain moksha (liberation), a human being must acquire self-knowledge.

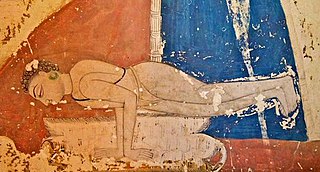

Moksha, also called vimoksha, vimukti, and mukti, is a term in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism for various forms of emancipation, liberation, nirvana, or release. In its soteriological and eschatological senses, it refers to freedom from saṃsāra, the cycle of death and rebirth. In its epistemological and psychological senses, moksha is freedom from ignorance: self-realization, self-actualization and self-knowledge.

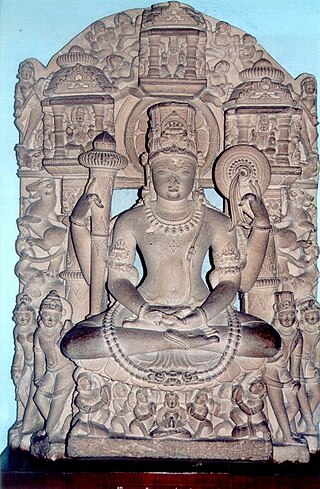

Hindu philosophy or Vedic philosophy is the set of Indian philosophical systems that developed in tandem with the religion of Hinduism during the iron and classical ages of India. In Indian tradition, the word used for philosophy is Darshana, from the Sanskrit root 'दृश' meaning 'to see, to experience'.

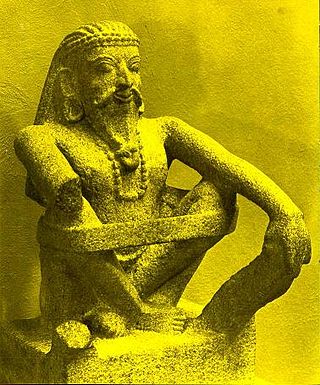

Samkhya or Sankhya is a dualistic orthodox school of Hindu philosophy. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, Puruṣa and Prakṛti.

Nondualism includes a number of philosophical and spiritual traditions that emphasize the absence of fundamental duality or separation in existence. This viewpoint questions the boundaries conventionally imposed between self and other, mind and body, observer and observed, and other dichotomies that shape our perception of reality. As a field of study, nondualism delves into the concept of nonduality and the state of nondual awareness, encompassing a diverse array of interpretations, not limited to a particular cultural or religious context; instead, nondualism emerges as a central teaching across various belief systems, inviting individuals to examine reality beyond the confines of dualistic thinking.

The Maitrayaniya Upanishad is an ancient Sanskrit text that is embedded inside the Yajurveda. It is also known as the Maitri Upanishad, and is listed as number 24 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads.

Avidyā is a Sanskrit word whose literal meaning is ignorance, misconceptions, misunderstandings, incorrect knowledge, and it is the opposite of Vidya. It is used extensively in Hindu texts, including the Upanishads, and in other Indian religions such as Buddhism and Jainism, particularly in the context of metaphysical reality.

The Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad is the shortest of all the Upanishads, and is assigned to Atharvaveda. It is listed as number 6 in the Muktikā canon of 108 Upanishads.

The Shvetashvatara Upanishad is an ancient Sanskrit text embedded in the Yajurveda. It is listed as number 14 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads. The Upanishad contains 113 mantras or verses in six chapters.

The Katha Upanishad is an ancient Hindu text and one of the mukhya (primary) Upanishads, embedded in the last eight short sections of the Kaṭha school of the Krishna Yajurveda. It is also known as Kāṭhaka Upanishad, and is listed as number 3 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads.

Dhyāna in Hinduism means contemplation and meditation. Dhyana is taken up in Yoga practices, and is a means to samadhi and self-knowledge.

The Nadabindu Upanishad is an ancient Sanskrit text and one of the minor Upanishads of Hinduism. It is one of twenty Yoga Upanishads in the four Vedas. It also known as Amrita Nada Bindu Upanishad.(Sanskrit: अमृतनादबिन्दु उपनिषद)

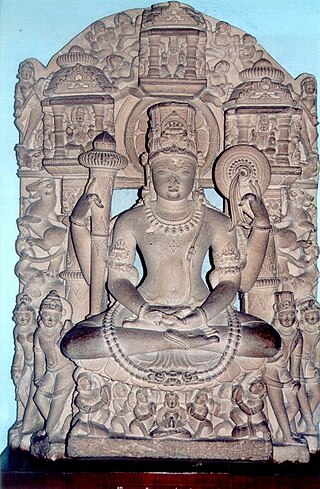

Yoga philosophy is one of the six major orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy, though it is only at the end of the first millennium CE that Yoga is mentioned as a separate school of thought in Indian texts, distinct from Samkhya. Ancient, medieval and most modern literature often refers to Yoga-philosophy simply as Yoga. A systematic collection of ideas of Yoga is found in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, a key text of Yoga which has influenced all other schools of Indian philosophy.

The Mantrika Upanishad is a minor Upanishad of Hinduism. The Sanskrit text is one of the 22 Samanya Upanishads, is part of the Vedanta and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy literature, and is one of 19 Upanishads attached to the Shukla Yajurveda. In the Muktika canon, narrated by Rama to Hanuman, it is listed at number 32 in the anthology of 108 Upanishads.

The Darshana Upanishad is one of the minor Upanishads of Hinduism written in Sanskrit. It is one of twenty Yoga Upanishads in the four Vedas, and it is attached to the Samaveda.

The Paingala Upanishad is an early medieval era Sanskrit text and is one of the general Upanishads of Hinduism. It is one of the 22 Samanya (general) Upanishads, and its manuscripts survive in modern times in two versions. The shorter version of the manuscript is found attached to the Atharvaveda, while the longer version is attached to the Shukla Yajurveda. It presents a syncretic view of Samkhya and Vedanta schools of Hindu philosophy.

The Trishikhibrahmana Upanishad, also known as Trisikhibrahmanopanisad, is one of the minor Upanishads of Hinduism and a Sanskrit text. It is attached to the Shukla Yajurveda and is classified as one of the 20 Yoga Upanishads.

The Mandala-brahmana Upanishad, also known as Mandalabrahmanopanisad, is one of the minor Upanishads of Hinduism and a Sanskrit text. It is attached to the Shukla Yajurveda and is classified as one of the 20 Yoga Upanishads.