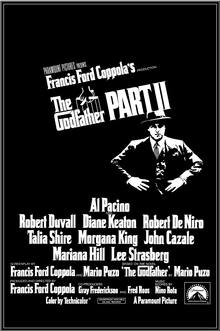

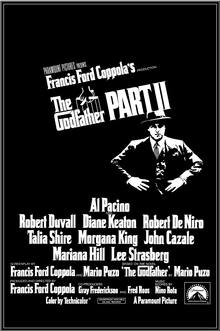

The Godfather Part II is a 1974 American epic crime film produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola. The film is partially based on the 1969 novel The Godfather by Mario Puzo, who co-wrote the screenplay with Coppola. Part II serves as both a sequel and a prequel to the 1972 film The Godfather, presenting parallel dramas: one picks up the 1958 story of Michael Corleone, the new Don of the Corleone family, protecting the family business in the aftermath of an attempt on his life; the prequel covers the journey of his father, Vito Corleone, from his Sicilian childhood to the founding of his family enterprise in New York City. The ensemble cast also features Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, Talia Shire, Morgana King, John Cazale, Mariana Hill, and Lee Strasberg.

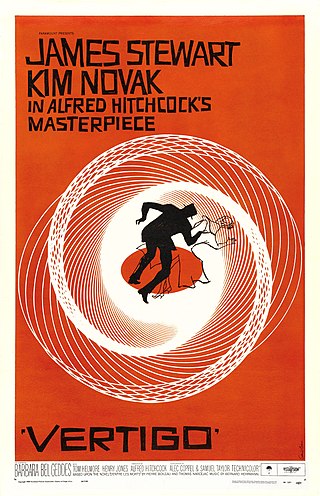

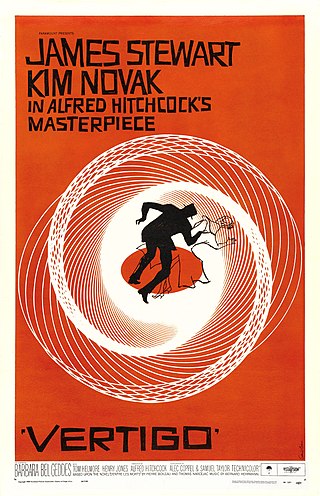

Vertigo is a 1958 American film noir psychological thriller film directed and produced by Alfred Hitchcock. The story was based on the 1954 novel D'entre les morts by Boileau-Narcejac. The screenplay was written by Alec Coppel and Samuel A. Taylor. The film stars James Stewart as former police detective John "Scottie" Ferguson, who has retired because an incident in the line of duty has caused him to develop acrophobia and vertigo. Scottie is hired by an acquaintance, Gavin Elster, as a private investigator to follow Gavin's wife Madeleine, who is behaving strangely.

Battleship Potemkin, sometimes rendered as Battleship Potyomkin, is a 1925 Soviet silent drama film produced by Mosfilm. Directed and co-written by Sergei Eisenstein, it presents a dramatization of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin rebelled against its officers.

Yasujirō Ozu was a Japanese film director and screenwriter. He began his career during the era of silent films, and his last films were made in colour in the early 1960s. Ozu first made a number of short comedies, before turning to more serious themes in the 1930s. The most prominent themes of Ozu's work are marriage and family, especially the relationships between generations. His most widely beloved films include Late Spring (1949), Tokyo Story (1953), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962).

Chantal Anne Akerman was a Belgian film director, screenwriter, artist, and film professor at the City College of New York. She is best known for films such as Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), News from Home (1977), and Les Rendez-vous d'Anna (1978); the former was ranked the greatest film of all time in Sight & Sound magazine's 2022 "Top 100 Greatest Films" critics poll. According to film scholar Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, Akerman's influence on feminist and avant-garde cinema is substantial.

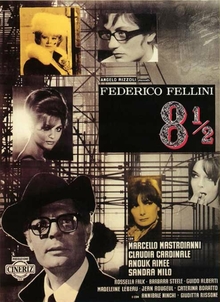

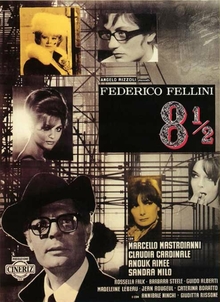

8+1⁄2 is a 1963 surrealist comedy-drama film directed and co-written by Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini. The metafictional narrative centers on Guido Anselmi, played by Marcello Mastroianni, a famous Italian film director who suffers from stifled creativity as he attempts to direct an epic science fiction film. Claudia Cardinale, Anouk Aimée, Sandra Milo, Rossella Falk, Barbara Steele, and Eddra Gale portray the various women in Guido's life. The film is shot in black and white by cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo and features a soundtrack by Nino Rota, with costume and set designs by Piero Gherardi.

The Apu Trilogy comprises three Indian Bengali-language drama films directed by Satyajit Ray: Pather Panchali (1955), Aparajito (1956) and The World of Apu (1959). The original music for the films was composed by Ravi Shankar.

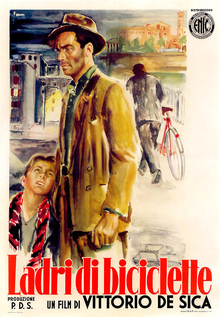

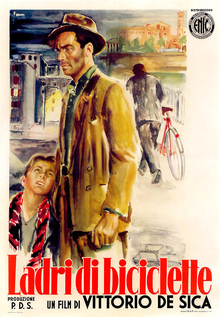

Bicycle Thieves is a 1948 Italian neorealist drama film directed by Vittorio De Sica. It follows the story of a poor father searching in post-World War II Rome for his stolen bicycle, without which he will lose the job which was to be the salvation of his young family.

Tokyo Story is a 1953 Japanese drama film directed by Yasujirō Ozu and starring Chishū Ryū and Chieko Higashiyama about an aging couple who travel to Tokyo to visit their grown children. Upon release, it did not immediately gain international recognition and was considered "too Japanese" to be marketable by Japanese film exporters. It was screened in 1957 in London, where it won the inaugural Sutherland Trophy the following year, and received praise from U.S. film critics after a 1972 screening in New York City.

Close-Up is a 1990 Iranian docufiction written, directed and edited by Abbas Kiarostami. The film tells the story of the real-life trial of a man who impersonated film-maker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, conning a family into believing they would star in his new film. It features the people involved, acting as themselves. A film about human identity, it helped to increase recognition of Kiarostami internationally.

David Denby is an American journalist. He served as film critic for The New Yorker until December 2014.

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is a 1975 drama film written and directed by Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman. It was filmed over five weeks on location in Brussels, and financed through a $120,000 grant awarded by the Belgian government. Distinguished by its restrained pace, long takes, and static camerawork, the film is a slice of life depiction of a widowed housewife over the course of three days.

Godfrey Cheshire III is an American film critic, film writer and director.

Nigel Andrews FRSA is a British film critic best known for being the long-time chief film critic of the Financial Times.

The Sight & Sounds Greatest Films of All Time 2012 was a worldwide opinion poll conducted by Sight & Sound and published in the magazine's September 2012 issue. Sight & Sound, published by the British Film Institute, has conducted a poll of the greatest films every 10 years since 1952. For this poll, Sight & Sound listened to decades of criticism about the lack of diversity of its poll participants and made a huge effort to invite a much wider variety of critics and filmmakers from around the world to participate, taking into account gender, ethnicity, race, geographical region, socioeconomic status, and other kinds of underrepresentation.

Geoff Andrew is a British writer and lecturer on film, and Programmer-at-large at BFI South Bank. After gaining a First in Classics at King's College, Cambridge, he was for some years programmer at London's Electric Cinema in Notting Hill, and later became the editor and chief critic of the film section of Time Out magazine.

The Great Movies is the name of several publications, both online and in print, from the film critic Roger Ebert. The object was, as Ebert put it, to "make a tour of the landmarks of the first century of cinema."

Modernist film is related to the art and philosophy of modernism.

The "Top 100 Greatest Films of All Time" is a list published every ten years by Sight & Sound according to worldwide opinion polls they conduct. They published the critics' list, based on 1,639 participating critics, programmers, curators, archivists and academics, and the directors' list, based on 480 directors and filmmakers. Sight & Sound, published by the British Film Institute, has conducted a poll of the greatest films every 10 years since 1952.