A public utility company is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service. Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and regulation ranging from local community-based groups to statewide government monopolies.

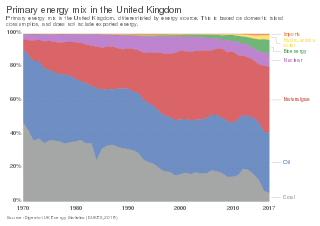

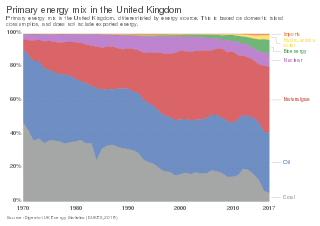

The energy policy of the United Kingdom refers to the United Kingdom's efforts towards reducing energy intensity, reducing energy poverty, and maintaining energy supply reliability. The United Kingdom has had success in this, though energy intensity remains high. There is an ambitious goal to reduce carbon dioxide emissions in future years, but it is unclear whether the programmes in place are sufficient to achieve this objective. Regarding energy self-sufficiency, UK policy does not address this issue, other than to concede historic energy security is currently ceasing to exist.

The electricity sector in Colombia is dominated by large hydropower generation (65%) and thermal generation (35%). Despite the country's large potential for new renewable energy technologies, this potential has been barely tapped. A 2001 law designed to promote alternative energies lacks certain key provisions to achieve this objective, such as feed-in tariffs, and has had little impact so far. Large hydropower and thermal plants dominate the current expansion plans. The construction of a transmission line with Panama, which will link Colombia with Central America, is underway.

The electricity sector in Argentina constitutes the third largest power market in Latin America. It relies mostly on thermal generation and hydropower generation (36%). The prevailing natural gas-fired thermal generation is at risk due to the uncertainty about future gas supply.

As required by the Constitution, the electricity sector is federally owned, with the Federal Electricity Commission essentially controlling the whole sector; private participation and foreign companies are allowed to operate in the country only through specific service contracts. Attempts to reform the sector have traditionally faced strong political and social resistance in Mexico, where subsidies for residential consumers absorb substantial fiscal resources.

An independent power producer (IPP) or non-utility generator (NUG) is an entity that is not a public utility but owns facilities to generate electric power for sale to utilities and end users. NUGs may be privately held facilities, corporations, cooperatives such as rural solar or wind energy producers, and non-energy industrial concerns capable of feeding excess energy into the system.

Electricity pricing can vary widely by country or by locality within a country. Electricity prices are dependent on many factors, such as the price of power generation, government taxes or subsidies, CO

2 taxes, local weather patterns, transmission and distribution infrastructure, and multi-tiered industry regulation. The pricing or tariffs can also differ depending on the customer-base, typically by residential, commercial, and industrial connections.

Energy laws govern the use and taxation of energy, both renewable and non-renewable. These laws are the primary authorities related to energy. In contrast, energy policy refers to the policy and politics of energy.

The electricity sector in Guyana is dominated by Guyana Power and Light (GPL), the state-owned vertically integrated utility. Although the country has a large potential for hydroelectric and bagasse-fueled power generation, most of its 226 MW of installed capacity correspond to thermoelectric diesel-engine driven generators.

The Ceylon Electricity Board - CEB, was the largest electricity company in Sri Lanka. With a market share of nearly 100%, it controlled all major functions of electricity generation, transmission, distribution and retailing in Sri Lanka. It was one of the only two on-grid electricity companies in the country; the other being Lanka Electricity Company (LECO). The company earned approximately Rs 204.7 billion in 2014, with a total of nearly 5.42 million consumer accounts. It was a government-owned and controlled utility of Sri Lanka that took care of the general energy facilities of the island. The Ministry of Power and Energy was the responsible ministry above the CEB. Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), established by the CEB Act No. 17 of 1969, was under the legal obligation to develop and maintain an efficient, coordinated and economical system of electricity supply in accordance with any licenses issued. The CEB was dissolved and replaced by 12 successor entities under the 2024 Electricity Act.

The electricity sector in Sri Lanka has a national grid which is primarily powered by hydroelectric power and thermal power, with sources such as photovoltaics and wind power in early stages of deployment. Although potential sites are being identified, other power sources such as geothermal, nuclear, solar thermal and wave power are not used in the power generation process for the national grid.

An electric utility, or a power company, is a company in the electric power industry that engages in electricity generation and distribution of electricity for sale generally in a regulated market. The electrical utility industry is a major provider of energy in most countries.

The United Kingdom is committed to legally binding greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets of 34% by 2020 and 80% by 2050, compared to 1990 levels, as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008. Decarbonisation of electricity generation will form a major part of this reduction and is essential before other sectors of the economy can be successfully decarbonised.

Most of Kenya's electricity is generated by renewable energy sources. Access to reliable, affordable, and sustainable energy is one of the 17 main goals of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Development of the energy sector is also critical to help Kenya achieve the goals in Kenya Vision 2030 to become a newly industrializing, middle-income country. With an installed power capacity of 2,819 MW, Kenya currently generates 826 MW hydroelectric power, 828 geothermal power, 749 MW thermal power, 331 MW wind power, and the rest from solar and biomass sources. Kenya is the largest geothermal energy producer in Africa and also has the largest wind farm on the continent. In March 2011, Kenya opened Africa's first carbon exchange to promote investments in renewable energy projects. Kenya has also been selected as a pilot country under the Scaling-Up Renewable Energy Programmes in Low Income Countries Programme to increase deployment of renewable energy solutions in low-income countries. Despite significant strides in renewable energy development, about a quarter of the Kenyan population still lacks access to electricity, necessitating policy changes to diversify the energy generation mix and promote public-private partnerships for financing renewable energy projects.

The Israel Public Utility Authority for Electricity is a government authority charged with providing utility services, setting tariffs, regulation, and oversight of the electricity market in Israel. Established in 1996, the Authority came into existence concurrently with the expiration of the 70-year-old concession of the Israel Electric Corporation (IEC), and pursuant to the Electricity Market Law of 1996. Its formation marked a significant shift in the regulation and oversight of electricity provision in Israel, transitioning from a system where the Electric Corporation itself managed various regulatory roles to an independent regulatory body.

The Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka is the government entity responsible for policy formulation and regulation of the electric power distribution, water supply, petroleum resources, and other public utilities in Sri Lanka.

The Lanka Electricity Company (Private) Limited, is one of two on-grid electricity companies in Sri Lanka; the other being the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB). Established as a private limited liability company registered under the Companies Act No. 17 of 1982, its shareholders are the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Urban Development Authority (UDA), the Treasury and four local government authorities. It is regulated by the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka. As of 2019, LECO sold 1,629.39 kilowatt-hours (5,865.8 MJ) of power to 588,879 consumers, and made revenues of රු.32,576,500,000.

The 2019 Sri Lanka electricity crisis was a crisis which happened nearly a month from 18 March to 10 April 2019 faced by Sri Lanka caused by a severe drought that depleted water levels at hydroelectric plants. Sri Lanka experienced rolling blackouts for three to five hours per day except on Sundays in all parts of the island nation at different time schedules that started from 24 March 2019 to present. This is regarded as one of the worst blackouts confronted in Sri Lanka since 2016 and the longest ever blackout recorded in history of the country. However it was revealed that the main electricity providing institution Ceylon Electricity Board had restricted the power supply to almost all regions of the country without proper prior notice and implemented a time schedule unofficially from 24 March 2019. However the Ministry of Power and Renewable Energy revealed that it didn't grant and approve permission to CEB to impose power cuts.