The history of Sri Lanka is unique because the relevance and richness of it extends beyond the areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. The early human remains which were found on the island of Sri Lanka date back to about 38,000 years ago.

The Parliament of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is the supreme legislative body of Sri Lanka. It alone possesses legislative supremacy and thereby ultimate power over all other political bodies in the island. It is modeled after the British Parliament.

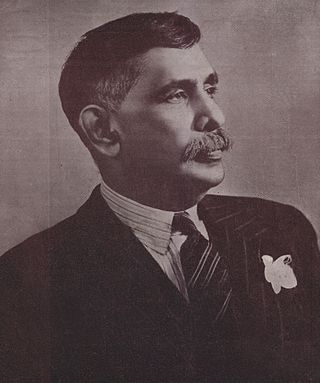

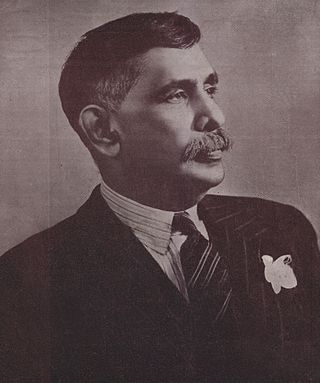

Don Stephen Senanayake was a Ceylonese statesman. He was the first Prime Minister of Ceylon having emerged as the leader of the Sri Lankan independence movement that led to the establishment of self-rule in Ceylon. He is considered as the "Father of the Nation".

Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike, known by the Sri Lankan people as "The Silver Bell of Asia", was the fourth Prime Minister of the Dominion of Ceylon, serving from 1956 until his assassination in 1959, causing him to die in office. The founder of the left-wing and Sinhalese nationalist Sri Lanka Freedom Party, his tenure saw the country's first left-wing reforms.

The Lanka Sama Samaja Party, often abbreviated as LSSP, is a major Trotskyist political party in Sri Lanka. It was the first political party in Sri Lanka, having been founded in 1935 by Leslie Goonewardene, N.M. Perera, Colvin R. de Silva, Philip Gunawardena and Robert Gunawardena. It currently is a member of the main ruling coalition in the government of Sri Lanka and is headed by Tissa Vitharana. The party was founded with Leninist ideals, and is classified as a party with socialist aims.

The Official Language Act , commonly referred to as the Sinhala Only Act, was an act passed in the Parliament of Ceylon in 1956. The act replaced English with Sinhala as the sole official language of Ceylon, with the exclusion of Tamil.

The Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka has been the constitution of the island nation of Sri Lanka since its original promulgation by the National State Assembly on 7 September 1978. As of October 2022 it has been formally amended 21 times.

Parliamentary elections were held in Sri Lanka on 21 July 1977. The result was a landslide victory for the United National Party, which won 140 of the 168 seats in the National State Assembly.

Parliamentary elections were held in Ceylon in 1970.

Samuel James Veluppillai Chelvanayakam was a Ceylonese lawyer, politician and Member of Parliament. He was the founder and leader of the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK) and Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and a political leader of the Ceylon Tamil community for more than two decades. Chelvanayakam has been described as a father figure to Ceylon's Tamils, to whom he was known as "Thanthai Chelva".

The Senate was the upper chamber of the parliament of Ceylon established in 1947 by the Soulbury Commission. The Senate was appointed and indirectly elected rather than directly elected. It was housed in the old Legislative Council building in Colombo Fort and met for the first time on 12 November 1947. The Senate was abolished on 2 October 1971 by the eighth amendment to the Soulbury Constitution, prior to the adoption of the new Republican Constitution of Sri Lanka on 22 May 1972. In 2010 there were proposals to reintroduce the Senate.

Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism is the conviction of the Sri Lankan Tamil people, a minority ethnic group in the South Asian island country of Sri Lanka, that they have the right to constitute an independent or autonomous political community. This idea has not always existed. Sri Lankan Tamil national awareness began during the era of British rule during the nineteenth century, as Tamil Hindu revivalists tried to counter Protestant missionary activity. The revivalists, led by Arumuga Navalar, used literacy as a tool to spread Hinduism and its principles.

The Ministry of External Affairs and Defence was a cabinet ministry of the Government of Ceylon that conducted and managed all of Ceylon's relations with other countries and its military matters from 1947 to 1977.

Upali Tissa Vitharana is a Sri Lankan politician, former Member of Parliament and former cabinet minister. He is the current leader of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), a member of the United People's Freedom Alliance (UPFA), and is serving as Governor of North Central Province.

The National State Assembly (NSA) was the legislative body of Sri Lanka established in May 1972 under the First Republican Constitution. The assembly was introduced by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike under the United Front Government replacing the Parliament of Ceylon, a bicameral arrangement set up with the Soulbury Commission.

The British Ceylon period is the history of Sri Lanka between 1815 and 1948. It follows the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom into the hands of the British Empire. It ended over 2300 years of Sinhalese monarchy rule on the island. The British rule on the island lasted until 1948 when the country regained independence following the Sri Lankan independence movement.

The Prime Minister of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is the head and most senior member of parliament in the cabinet of ministers. It is the second-most powerful position in Sri Lanka's executive branch behind the president, who is the constitutional chief executive. The Cabinet is collectively held accountable to parliament for their policies and actions.

The Second Sirimavo Bandaranaike cabinet was the central government of Ceylon led by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike between 1970 and 1977. It was formed in May 1970 after the parliamentary election and it ended in July 1977 after the opposition's victory in the parliamentary election. The second Sirimavo Bandaranaike cabinet saw Ceylon severing the last colonial ties with Britain as the country became a parliamentary republic in May 1972. The country was also renamed Sri Lanka.

The 19th Amendment (19A) to the Constitution of Sri Lanka was passed by the 225-member Sri Lankan Parliament with 215 voting in favor, one against, one abstained and seven were absent, on 28 April 2015. The amendment envisages the dilution of many powers of Executive Presidency, which had been in force since 1978. It is the most revolutionary reform ever applied to the Constitution of Sri Lanka since JR Jayawardhane became the first Executive President of Sri Lanka in 1978.

George Reginald de Silva was a Ceylonese politician.