The history of Sri Lanka is unique because its relevance and richness extend beyond the areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. The early human remains which were found on the island of Sri Lanka date back to about 38,000 years ago.

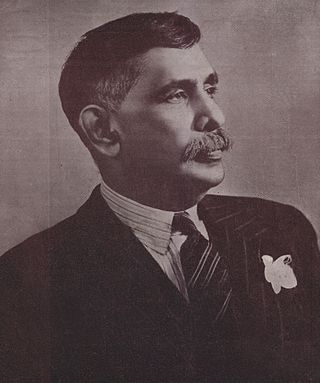

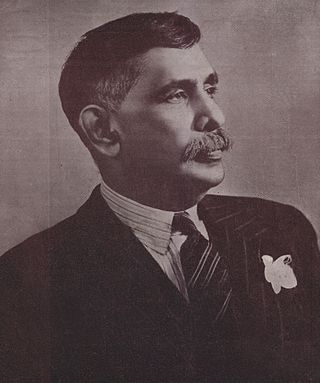

Don Stephen Senanayake was a Ceylonese statesman. He was the first Prime Minister of Ceylon, having emerged as the leader of the Sri Lankan independence movement that led to the establishment of self-rule in Ceylon. He is considered as the "Father of the Nation".

Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike, also known as "The Silver Bell of Asia", was a Ceylonese statesman who served as the fourth Prime Minister of the Dominion of Ceylon, serving from 1956 until his assassination. The founder of the left-wing and Sinhalese nationalist Sri Lanka Freedom Party, his tenure saw the country's first left-wing reforms.

The Ceylon Workers' Congress (CWC) is a political party in Sri Lanka that has traditionally represented Sri Lankan Tamils of Indian origin working in the plantation sector of the economy.

Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka are Tamil people of Indian origin in Sri Lanka. They are also known as Malayaga Tamilar, Hill Country Tamils, Up-Country Tamils or simply Indian Tamils. They predominantly descend from workers sent during the British Raj from Southern India to Sri Lanka in the 19th and 20th centuries to work in coffee, tea and rubber plantations. Some also migrated on their own as merchants and as other service providers. These Tamil speakers mostly live in the central highlands, also known as the Malayakam or Hill Country, yet others are also found in major urban areas and in the Northern Province. Although they are all termed as Tamils today, some have Telugu and Malayalee origins as well as diverse South Indian caste origins. They are instrumental in the plantation sector economy of Sri Lanka. In general, socio-economically their standard of living is below that of the national average and they are described as one of the poorest and most neglected groups in Sri Lanka. In 1964 a large percentage were repatriated to India, but left a considerable number as stateless people. By the 1990s most of these had been given Sri Lankan citizenship. Most are Hindus with a minority of Christians and Muslims amongst them. There are also a small minority followers of Buddhism among them. Politically they are supportive of trade union-based political parties that have supported most of the ruling coalitions since the 1980s.

The Sri Lankan independence movement was a peaceful political movement which was aimed at achieving independence and self-rule for the country of Sri Lanka, then British Ceylon, from the British Empire. The switch of powers was generally known as peaceful transfer of power from the British administration to Ceylon representatives, a phrase that implies considerable continuity with a colonial era that lasted 400 years. It was initiated around the turn of the 20th century and led mostly by the educated middle class. It succeeded when, on 4 February 1948, Ceylon was granted independence as the Dominion of Ceylon. Dominion status within the British Commonwealth was retained for the next 24 years until 22 May 1972 when it became a republic and was renamed the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

The Official Language Act , commonly referred to as the Sinhala Only Act, was an act passed in the Parliament of Ceylon in 1956. The act replaced English with Sinhala as the sole official language of Ceylon, with the exclusion of Tamil from the act.

Sir Oliver Ernest Goonetilleke was a Sri Lankan statesman. Having served as an important figure in the gradual independence of Ceylon from Britain, he became the third Governor-General of Ceylon (1954–1962). He was the first Ceylonese individual to hold the vice-regal post.

The Donoughmore Constitution, created by the Donoughmore Commission, served Sri Lanka (Ceylon) from 1931 to 1947 when it was replaced by the Soulbury Constitution.

The Donoughmore Commission (DC) was responsible for the creation of the Donoughmore Constitution in effect between 1931 and 1947 in Ceylon. In 1931 there were approximately 12% Ceylonese Tamils, 12% Indian Tamils, 65% Sinhalese, and ~3% Ceylon Moors. The British government had introduced a form of communal representation which a strong Tamil representation, out of proportion to the population of the Tamil community. The Sinhalese had been divided into up-country and low-country Sinhalese.

Ganapathipillai Gangaser Ponnambalam was a Ceylon Tamil lawyer, politician and cabinet minister. He was the founder and leader of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress (ACTC), the first political party to represent the Ceylon Tamils.

Samuel James Veluppillai Chelvanayakam was a Ceylonese lawyer, politician and Member of Parliament. He was the founder and leader of the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK) and Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and a political leader of the Ceylon Tamil community for more than two decades. Chelvanayakam has been described as a father figure to Ceylon's Tamils, to whom he was known as "Thanthai Chelva".

The origins of the Sri Lankan Civil War lie in the continuous political rancor between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Sri Lankan Tamils. The war has been described by social anthropologist Jonathan Spencer as an outcome of how modern ethnic identities have been made and re-made since the colonial period, with the political struggle between minority Tamils and the Sinhalese-dominant government accompanied by rhetorical wars over archeological sites and place name etymologies, and the political use of the national past.

British Ceylon, officially British Settlements and Territories in the Island of Ceylon with its Dependencies from 1802 to 1833, then the Island of Ceylon and its Territories and Dependencies from 1833 to 1931 and finally the Island of Ceylon and its Dependencies from 1931 to 1948, was the British Crown colony of present-day Sri Lanka between 1796 and 4 February 1948. Initially, the area it covered did not include the Kingdom of Kandy, which was a protectorate, but from 1817 to 1948 the British possessions included the whole island of Ceylon, now the nation of Sri Lanka.

Sir Edwin Aloysius Perera Wijeyeratne, known as Edwin Wijeyeratne, was a Sri Lankan lawyer, politician, diplomat, and one of the founding members of the Ceylon National Congress and the United National Party. He was a Senator and Minister of Home Affairs and Rural Development in the cabinet of D. S. Senanayake. He thereafter he served as Ceylonese High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and Ceylonese High Commissioner to India

Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism is the conviction of the Sri Lankan Tamil people, a minority ethnic group in the South Asian island country of Sri Lanka, that they have the right to constitute an independent or autonomous political community. This idea has not always existed. Sri Lankan Tamil national awareness began during the era of British rule during the nineteenth century, as Tamil Hindu revivalists tried to counter Protestant missionary activity. The revivalists, led by Arumuga Navalar, used literacy as a tool to spread Hinduism and its principles.

The Legislative Council of Ceylon was the legislative body of Ceylon established in 1833, along with the Executive Council of Ceylon, on the recommendations of the Colebrooke-Cameron Commission. It was the first form of representative government in the island. The 1931 Donoughmore Constitution replaced the Legislative Council with the State Council of Ceylon.

The Bandaranaike–Chelvanayakam Pact was an agreement signed between the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike and the leader of the main Tamil political party in Sri Lanka S. J. V. Chelvanayakam on July 26, 1957. It advocated the creation of a series of regional councils in Sri Lanka as a means to giving a certain level of autonomy to the Tamil people of the country, and was intended to solve the communal disagreements that were occurring in the country at the time.

The 1915 Sinhalese-Muslim riots was a widespread and prolonged ethnic riot in the island of Ceylon between Sinhalese Buddhists and the Ceylon Moors. The riots were eventually suppressed by the British colonial authorities.

The Ceylon National Congress (CNC) was a political party in colonial-era Ceylon founded on 11 December 1919. It was founded during a period where nationalism and support for the Sri Lankan independence movement grew quite intensely amidst British colonial rule in Ceylon. It was formed by members of the Ceylon National Association and the Ceylon Reform League.