Bycatch, in the fishing industry, is a fish or other marine species that is caught unintentionally while fishing for specific species or sizes of wildlife. Bycatch is either the wrong species, the wrong sex, or is undersized or juveniles of the target species. The term "bycatch" is also sometimes used for untargeted catch in other forms of animal harvesting or collecting. Non-marine species that are caught but regarded as generally "undesirable" are referred to as rough fish or coarse fish.

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally, resulting in the species becoming increasingly underpopulated in that area. Overfishing can occur in water bodies of any sizes, such as ponds, wetlands, rivers, lakes or oceans, and can result in resource depletion, reduced biological growth rates and low biomass levels. Sustained overfishing can lead to critical depensation, where the fish population is no longer able to sustain itself. Some forms of overfishing, such as the overfishing of sharks, has led to the upset of entire marine ecosystems. Types of overfishing include growth overfishing, recruitment overfishing, and ecosystem overfishing. Overfishing not only causes negative impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, but also reduces fish production, which subsequently leads to negative social and economic consequences.

A conventional idea of a sustainable fishery is that it is one that is harvested at a sustainable rate, where the fish population does not decline over time because of fishing practices. Sustainability in fisheries combines theoretical disciplines, such as the population dynamics of fisheries, with practical strategies, such as avoiding overfishing through techniques such as individual fishing quotas, curtailing destructive and illegal fishing practices by lobbying for appropriate law and policy, setting up protected areas, restoring collapsed fisheries, incorporating all externalities involved in harvesting marine ecosystems into fishery economics, educating stakeholders and the wider public, and developing independent certification programs.

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity that takes, cultures, processes, preserves, stores, transports, markets or sells fish or fish products. It is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization as including recreational, subsistence and commercial fishing, as well as the related harvesting, processing, and marketing sectors. The commercial activity is aimed at the delivery of fish and other seafood products for human consumption or as input factors in other industrial processes. The livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends directly or indirectly on fisheries and aquaculture.

The goal of fisheries management is to produce sustainable biological, environmental and socioeconomic benefits from renewable aquatic resources. Wild fisheries are classified as renewable when the organisms of interest produce an annual biological surplus that with judicious management can be harvested without reducing future productivity. Fishery management employs activities that protect fishery resources so sustainable exploitation is possible, drawing on fisheries science and possibly including the precautionary principle.

Commercial fishing is the activity of catching fish and other seafood for commercial profit, mostly from wild fisheries. It provides a large quantity of food to many countries around the world, but those who practice it as an industry must often pursue fish far into the ocean under adverse conditions. Large-scale commercial fishing is called industrial fishing.

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is a non-profit organisation which aims to set standards for sustainable fishing. Fisheries that wish to demonstrate they are well-managed and sustainable compared to the MSC's standards are assessed by a team of Conformity Assessment Bodies (CABs).

The Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSFCMA), commonly referred to as the Magnuson–Stevens Act (MSA), is the legislation providing for the management of marine fisheries in U.S. waters. Originally enacted in 1976 to assert control of foreign fisheries that were operating within 200 nautical miles off the U.S. coast, the legislation has since been amended, in 1996 and 2007, to better address the twin problems of overfishing and overcapacity. These ecological and economic problems arose in the domestic fishing industry as it grew to fill the vacuum left by departing foreign fishing fleets.

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), informally known as NOAA Fisheries, is a United States federal agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that is responsible for the stewardship of U.S. national marine resources. It conserves and manages fisheries to promote sustainability and prevent lost economic potential associated with overfishing, declining species, and degraded habitats.

The skipjack tuna is a perciform fish in the tuna family, Scombridae, and is the only member of the genus Katsuwonus. It is also known as katsuo, arctic bonito, mushmouth, oceanic bonito, striped tuna or victor fish. It grows up to 1 m (3 ft) in length. It is a cosmopolitan pelagic fish found in tropical and warm-temperate waters. It is a very important species for fisheries. It is also the namesake of the USS Skipjack.

Unsustainable fishing methods refers to the use of various fishing methods to capture or harvest fish at a rate that is unsustainable for fish populations. These methods facilitate destructive fishing practices that damage ocean ecosystems, resulting in overfishing.

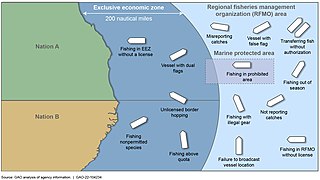

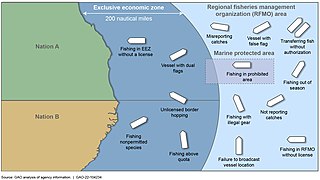

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) is an issue around the world. Fishing industry observers believe IUU occurs in most fisheries, and accounts for up to 30% of total catches in some important fisheries.

The environmental impact of fishing includes issues such as the availability of fish, overfishing, fisheries, and fisheries management; as well as the impact of industrial fishing on other elements of the environment, such as bycatch. These issues are part of marine conservation, and are addressed in fisheries science programs. According to a 2019 FAO report, global production of fish, crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic animals has continued to grow and reached 172.6 million tonnes in 2017, with an increase of 4.1 percent compared with 2016. There is a growing gap between the supply of fish and demand, due in part to world population growth.

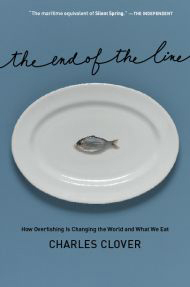

The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat is a book by journalist Charles Clover about overfishing. It was made into a movie released in 2009 and was re-released with updates in 2017.

Sustainable seafood is seafood that is caught or farmed in ways that consider the long-term vitality of harvested species and the well-being of the oceans, as well as the livelihoods of fisheries-dependent communities. It was first promoted through the sustainable seafood movement which began in the 1990s. This operation highlights overfishing and environmentally destructive fishing methods. Through a number of initiatives, the movement has increased awareness and raised concerns over the way our seafood is obtained.

Friend of the Sea is a project of the World Sustainability Organization for the certification and promotion of seafood from sustainable fisheries and sustainable aquaculture. It is the only certification scheme which, with the same logo, certifies both wild and farmed seafood.

A community-supported fishery (CSF) is an alternative business model for selling fresh, locally sourced seafood. CSF programs, modeled after increasingly popular community-supported agriculture programs, offer members weekly shares of fresh seafood for a pre-paid membership fee. The first CSF program was started in Port Clyde, Maine, in 2007, and similar CSF programs have since been started across the United States and in Europe. Community supported fisheries aim to promote a positive relationship between fishermen, consumers, and the ocean by providing high-quality, locally caught seafood to members. CSF programs began as a method to help marine ecosystems recover from the effects of overfishing while maintaining a thriving fishing community.

The Marine Conservation Alliance (MCA) is a Juneau, Alaska-based coalition of seafood processors, harvesters, support industries and coastal communities that participate in Alaska fisheries. The coalition was established in 2001 by fishery associations, communities, Community Development Quota (CDQ) groups, harvesters, processors and support businesses, to promote science-based conservation measures to ensure sustainable Alaska fisheries.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to fisheries:

The Magnuson-Stevens Act Provisions is necessary to help compliance the requirements of the MSA to end and prevent overfishing, rebuild overfished stocks, and achieve maximum yield