Related Research Articles

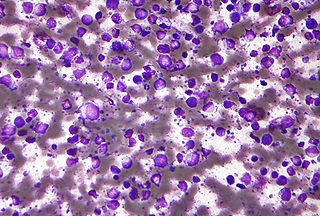

Tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues or tumours of the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues are tumors that affect the blood, bone marrow, lymph, and lymphatic system. Because these tissues are all intimately connected through both the circulatory system and the immune system, a disease affecting one will often affect the others as well, making aplasia, myeloproliferation and lymphoproliferation closely related and often overlapping problems. While uncommon in solid tumors, chromosomal translocations are a common cause of these diseases. This commonly leads to a different approach in diagnosis and treatment of hematological malignancies. Hematological malignancies are malignant neoplasms ("cancer"), and they are generally treated by specialists in hematology and/or oncology. In some centers "hematology/oncology" is a single subspecialty of internal medicine while in others they are considered separate divisions. Not all hematological disorders are malignant ("cancerous"); these other blood conditions may also be managed by a hematologist.

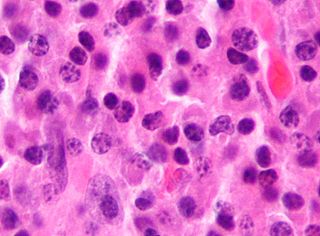

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in which aberrant T cells proliferate uncontrollably. Considered as a single entity, ALCL is the most common type of peripheral lymphoma and represents ~10% of all peripheral lymphomas in children. The incidence of ALCL is estimated to be 0.25 cases per 100,000 people in the United States of America. There are four distinct types of anaplastic large-cell lymphomas that on microscopic examination share certain key histopathological features and tumor marker proteins. However, the four types have very different clinical presentations, gene abnormalities, prognoses, and/or treatments.

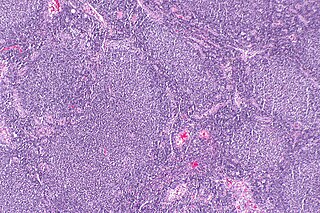

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a cancer that involves certain types of white blood cells known as lymphocytes. The cancer originates from the uncontrolled division of specific types of B-cells known as centrocytes and centroblasts. These cells normally occupy the follicles (nodular swirls of various types of lymphocytes) in the germinal centers of lymphoid tissues such as lymph nodes. The cancerous cells in FL typically form follicular or follicle-like structures (see adjacent Figure) in the tissues they invade. These structures are usually the dominant histological feature of this cancer.

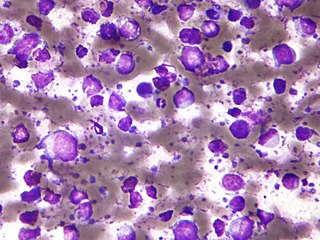

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is classified as a diffuse large B cell lymphoma. It is a rare malignancy of plasmablastic cells that occurs in individuals that are infected with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Plasmablasts are immature plasma cells, i.e. lymphocytes of the B-cell type that have differentiated into plasmablasts but because of their malignant nature do not differentiate into mature plasma cells but rather proliferate excessively and thereby cause life-threatening disease. In PEL, the proliferating plasmablastoid cells commonly accumulate within body cavities to produce effusions, primarily in the pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal cavities, without forming a contiguous tumor mass. In rare cases of these cavitary forms of PEL, the effusions develop in joints, the epidural space surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and underneath the capsule which forms around breast implants. Less frequently, individuals present with extracavitary primary effusion lymphomas, i.e., solid tumor masses not accompanied by effusions. The extracavitary tumors may develop in lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, the gastrointestinal tract, skin, spleen, liver, lungs, central nervous system, testes, paranasal sinuses, muscle, and, rarely, inside the vasculature and sinuses of lymph nodes. As their disease progresses, however, individuals with the classical effusion-form of PEL may develop extracavitary tumors and individuals with extracavitary PEL may develop cavitary effusions.

Nodular fasciitis (NF) is a benign, soft tissue tumor composed of myofibroblasts that typically occurs in subcutaneous tissue, fascia, and/or muscles. The literature sometimes titles rare NF variants according to their tissue locations. The most frequently used and important of these are cranial fasciitis and intravascular fasciitis. In 2020, the World Health Organization classified nodular fasciitis as in the category of benign fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tumors. NF is the most common of the benign fibroblastic proliferative tumors of soft tissue.

The B-cell lymphomas are types of lymphoma affecting B cells. Lymphomas are "blood cancers" in the lymph nodes. They develop more frequently in older adults and in immunocompromised individuals.

Intravascular lymphomas (IVL) are rare cancers in which malignant lymphocytes proliferate and accumulate within blood vessels. Almost all other types of lymphoma involve the proliferation and accumulation of malignant lymphocytes in lymph nodes, other parts of the lymphatic system, and various non-lymphatic organs but not in blood vessels.

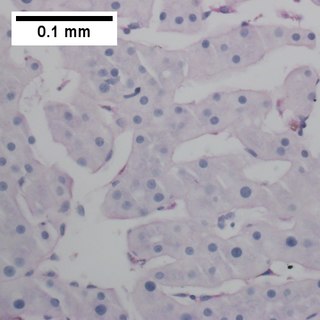

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) is a type of cancer made up of B-cells that replace the normal architecture of the white pulp of the spleen. The neoplastic cells are both small lymphocytes and larger, transformed lymphoblasts, and they invade the mantle zone of splenic follicles and erode the marginal zone, ultimately invading the red pulp of the spleen. Frequently, the bone marrow and splenic hilar lymph nodes are involved along with the peripheral blood. The neoplastic cells circulating in the peripheral blood are termed villous lymphocytes due to their characteristic appearance.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a cancer of B cells, a type of lymphocyte that is responsible for producing antibodies. It is the most common form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among adults, with an annual incidence of 7–8 cases per 100,000 people per year in the US and UK. This cancer occurs primarily in older individuals, with a median age of diagnosis at ~70 years, although it can occur in young adults and, in rare cases, children. DLBCL can arise in virtually any part of the body and, depending on various factors, is often a very aggressive malignancy. The first sign of this illness is typically the observation of a rapidly growing mass or tissue infiltration that is sometimes associated with systemic B symptoms, e.g. fever, weight loss, and night sweats.

Richter's transformation (RT), also known as Richter's syndrome, is the conversion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or its variant, small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), into a new and more aggressively malignant disease. CLL is the circulation of malignant B lymphocytes with or without the infiltration of these cells into lymphatic or other tissues while SLL is the infiltration of these malignant B lymphocytes into lymphatic and/or other tissues with little or no circulation of these cells in the blood. CLL along with its SLL variant are grouped together in the term CLL/SLL.

Marginal zone B-cell lymphomas, also known as marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs), are a heterogeneous group of lymphomas that derive from the malignant transformation of marginal zone B-cells. Marginal zone B cells are innate lymphoid cells that normally function by rapidly mounting IgM antibody immune responses to antigens such as those presented by infectious agents and damaged tissues. They are lymphocytes of the B-cell line that originate and mature in secondary lymphoid follicles and then move to the marginal zones of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, the spleen, or lymph nodes. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue is a diffuse system of small concentrations of lymphoid tissue found in various submucosal membrane sites of the body such as the gastrointestinal tract, mouth, nasal cavity, pharynx, thyroid gland, breast, lung, salivary glands, eye, skin and the human spleen.

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) is a slow-growing CD20 positive form of Hodgkin lymphoma, a cancer of the immune system's B cells.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTCL-NT) is a rare type of lymphoma that commonly involves midline areas of the nasal cavity, oral cavity, and/or pharynx At these sites, the disease often takes the form of massive, necrotic, and extremely disfiguring lesions. However, ENKTCL-NT can also involve the eye, larynx, lung, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and various other tissues. ENKTCL-NT mainly affects adults; it is relatively common in Asia and to lesser extents Mexico, Central America, and South America but is rare in Europe and North America. In Korea, ENKTCL-NT often involves the skin and is reported to be the most common form of cutaneous lymphoma after mycosis fungoides.

Epstein–Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative diseases are a group of disorders in which one or more types of lymphoid cells, i.e. B cells, T cells, NK cells, and histiocytic-dendritic cells, are infected with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). This causes the infected cells to divide excessively, and is associated with the development of various non-cancerous, pre-cancerous, and cancerous lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). These LPDs include the well-known disorder occurring during the initial infection with the EBV, infectious mononucleosis, and the large number of subsequent disorders that may occur thereafter. The virus is usually involved in the development and/or progression of these LPDs although in some cases it may be an "innocent" bystander, i.e. present in, but not contributing to, the disease.

Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T cell lymphoma (MEITL) is an extremely rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma that involves the malignant proliferation of a type of lymphocyte, the T cell, in the gastrointestinal tract. Over time, these T cells commonly spread throughout the mucosal lining of a portion of the GI tract, lead to GI tract nodules and ulcerations, and cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, diarrhea, obstruction, bleeding, and/or perforation.

Pediatric-type follicular lymphoma (PTFL) is a disease in which malignant B-cells accumulate in, overcrowd, and cause the expansion of the lymphoid follicles in, and thereby enlargement of the lymph nodes in the head and neck regions and, less commonly, groin and armpit regions. The disease accounts for 1.5% to 2% of all the lymphomas that occur in the pediatric age group.

Primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PT-DLBCL), also termed testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the testes, is a variant of the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL). DLBCL are a large and diverse group of B-cell malignancies with the great majority (-85%) being typed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. PT-DLBCL is a variant of DLBCL, NOS that involves one or, in uncommon cases, both testicles. Other variants and subtypes of DLBCL may involve the testes by spreading to them from their primary sites of origin in other tissues. PT-DLBCL differs from these other DLBCL in that it begins in the testes and then may spread to other sites.

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (PCDLBCL-LT) is a cutaneous lymphoma skin disease that occurs mostly in elderly females. In this disease, B cells become malignant, accumulate in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue below the dermis to form red and violaceous skin nodules and tumors. These lesions typically occur on the lower extremities but in uncommon cases may develop on the skin at virtually any other site. In ~10% of cases, the disease presents with one or more skin lesions none of which are on the lower extremities; the disease in these cases is sometimes regarded as a variant of PCDLBL, LT termed primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other (PCDLBC-O). PCDLBCL, LT is a subtype of the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) and has been thought of as a cutaneous counterpart to them. Like most variants and subtypes of the DLBCL, PCDLBCL, LT is an aggressive malignancy. It has a 5-year overall survival rate of 40–55%, although the PCDLBCL-O variant has a better prognosis than cases in which the legs are involved.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation (DLBCL-CI) is a subtype of the Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and a rare form of the Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative diseases, i.e. conditions in which lymphocytes infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) proliferate excessively in one or more tissues. EBV infects ~95% of the world's population to cause no symptoms, minor non-specific symptoms, or infectious mononucleosis. The virus then enters a latency phase in which the infected individual becomes a lifetime asymptomatic carrier of the virus. Some weeks, months, years, or decades thereafter, a very small fraction of these carriers, particularly those with an immunodeficiency, develop any one of various EBV-associated benign or malignant diseases.

Fibrin-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (FA-DLBCL) is an extremely rare form of the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL). DLBCL are lymphomas in which a particular type of lymphocyte, the B-cell, proliferates excessively, invades multiple tissues, and often causes life-threatening tissue damage. DLBCL have various forms as exemplified by one of its subtypes, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation (DLBCL-CI). DLBCL-CI is an aggressive malignancy that develops in sites of chronic inflammation that are walled off from the immune system. In this protected environment, the B-cells proliferate excessively, acquire malignant gene changes, form tumor masses, and often spread outside of the protected environment. In 2016, the World Health Organization provisionally classified FA-DLBCL as a DLBCL-CI. Similar to DLBCL-CI, FA-DLBCL involves the proliferation of EBV-infected large B-cells in restricted anatomical spaces that afford protection from an individual's immune system. However, FA-DLBCL differs from DLBCL-CI in many other ways, including, most importantly, its comparatively benign nature. Some researchers have suggested that this disease should be regarded as a non-malignant or pre-malignant lymphoproliferative disorder rather than a malignant DLBCL-CI.

References

- 1 2 Conte GA, Harmon JS, Le ML, Sun X, Schuler JW, Levitt MJ, Chinnici AA, Hossain MA (December 2019). "Hypercalcemia in T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma: An Unusual Presentation of a Rare Disease and Literature Review". World Journal of Oncology. 10 (6): 231–236. doi:10.14740/wjon1246. PMC 6940034 . PMID 31921379.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sukswai N, Lyapichev K, Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ (November 2019). "Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma variants: an update". Pathology. 52 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2019.08.013. PMID 31735345. S2CID 208142227.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Korkolopoulou P, Vassilakopoulos T, Milionis V, Ioannou M (July 2016). "Recent Advances in Aggressive Large B-cell Lymphomas: A Comprehensive Review". Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 23 (4): 202–43. doi:10.1097/PAP.0000000000000117. PMID 27271843. S2CID 205915174.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hartmann S, Eichenauer DA (January 2020). "Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma: pathology, clinical course and relation to T-cell/histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma". Pathology. 52 (1): 142–153. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2019.10.003. PMID 31785822. S2CID 208537001.

- ↑ Grimm KE, O'Malley DP (February 2019). "Aggressive B cell lymphomas in the 2017 revised WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 38: 6–10. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.09.014. PMID 30380402. S2CID 53196244.

- 1 2 Wei C, Wei C, Alhalabi O, Chen L (June 2018). "T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma in a child: A case report and review of literature". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 6 (6): 121–126. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i6.121 . PMC 6033745 . PMID 29988902.

- 1 2 3 Silva RNF, Mendonça EF, Batista AC, Alencar RCG, Mesquita RA, Costa NL (December 2019). "T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Report of the First Case in the Mandible". Head and Neck Pathology. 13 (4): 711–717. doi:10.1007/s12105-018-0948-9. PMC 6854205 . PMID 30019325.

- 1 2 3 4 Zheng SM, Zhou DJ, Chen YH, Jiang R, Wang YX, Zhang Y, Xue HL, Wang HQ, Mou D, Zeng WZ (June 2017). "Pancreatic T/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: A case report and review of literature". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 23 (24): 4467–4472. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4467 . PMC 5487512 . PMID 28706431.

- ↑ Barut F, Kandemir NO, Gun BD, Ozdamar SO (July 2016). "T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma of stomach". The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 66 (7): 905–7. PMID 27427148.

- ↑ Papoudou-Bai A, Hatzimichael E, Barbouti A, Kanavaros P (August 2017). "Expression patterns of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) family members in lymphoid neoplasms". Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 17 (3): 291–304. doi:10.1007/s10238-016-0436-z. PMID 27600282. S2CID 4778071.

- ↑ Low HB, Zhang Y (April 2016). "Regulatory Roles of MAPK Phosphatases in Cancer". Immune Network. 16 (2): 85–98. doi:10.4110/in.2016.16.2.85. PMC 4853501 . PMID 27162525.

- ↑ Pan H, Lv W, Li Z, Han W (2019). "SGK1 protein expression is a prognostic factor of lung adenocarcinoma that regulates cell proliferation and survival". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 12 (2): 391–408. PMC 6945076 . PMID 31933845.

- ↑ Beaurivage C, Champagne A, Tobelaim WS, Pomerleau V, Menendez A, Saucier C (June 2016). "SOCS1 in cancer: An oncogene and a tumor suppressor". Cytokine. 82: 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2016.01.005. PMID 26811119.

- ↑ Meyer SN, Scuoppo C, Vlasevska S, Bal E, Holmes AB, Holloman M, Garcia-Ibanez L, Nataraj S, Duval R, Vantrimpont T, Basso K, Brooks N, Dalla-Favera R, Pasqualucci L (September 2019). "Unique and Shared Epigenetic Programs of the CREBBP and EP300 Acetyltransferases in Germinal Center B Cells Reveal Targetable Dependencies in Lymphoma". Immunity. 51 (3): 535–547.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.006 . PMC 7362711 . PMID 31519498.

- ↑ Kober-Hasslacher M, Schmidt-Supprian M (July 2019). "The Unsolved Puzzle of c-Rel in B Cell Lymphoma". Cancers. 11 (7): 941. doi: 10.3390/cancers11070941 . PMC 6678315 . PMID 31277480.

- ↑ Liu Y, Barta SK (May 2019). "Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment". American Journal of Hematology. 94 (5): 604–616. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25460 . PMID 30859597.

- ↑ Schuhmacher B, Bein J, Rausch T, Benes V, Tousseyn T, Vornanen M, Ponzoni M, Thurner L, Gascoyne R, Steidl C, Küppers R, Hansmann ML, Hartmann S (February 2019). "JUNB, DUSP2, SGK1, SOCS1 and CREBBP are frequently mutated in T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma". Haematologica. 104 (2): 330–337. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.203224. PMC 6355500 . PMID 30213827.