The music of the United States reflects the country's pluri-ethnic population through a diverse array of styles. It is a mixture of music influenced by the music of the United Kingdom, West Africa, Ireland, Latin America, and mainland Europe, among other places. The country's most internationally renowned genres are jazz, blues, country, bluegrass, rock, rock and roll, R&B, pop, hip hop, soul, funk, gospel, disco, house, techno, ragtime, doo-wop, folk music, americana, boogaloo, tejano, reggaeton, surf, and salsa. American music is heard around the world. Since the beginning of the 20th century, some forms of American popular music have gained a near global audience.

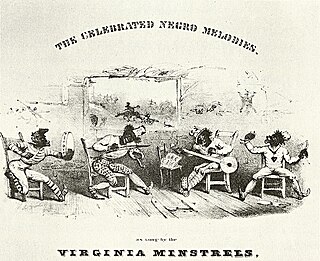

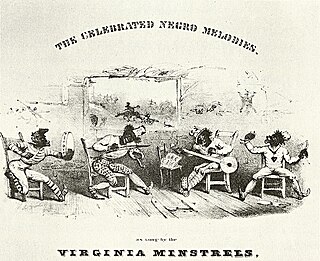

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of racist entertainment developed in the early 19th century. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people specifically of African descent. The shows were performed by mostly white people in make-up or blackface for the purpose of playing the role of black people. There were also some African-American performers and black-only minstrel groups that formed and toured. Minstrel shows lampooned black people as dim-witted, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky.

Themusic of Italy has traditionally been one of the cultural markers of Italian national and ethnic identity and holds an important position in society and in politics. Italian music innovation – in musical scale, harmony, notation, and theatre – enabled the development of opera, in the late 16th century, and much of modern European classical music – such as the symphony and concerto – ranges across a broad spectrum of opera and instrumental classical music and popular music drawn from both native and imported sources.

The latter part of the 19th century saw the increased popularization of African American music and the growth and maturity of folk styles like the blues.

American popular music has had a profound effect on music across the world. The country has seen the rise of popular styles that have had a significant influence on global culture, including ragtime, blues, jazz, swing, rock, bluegrass, country, R&B, doo wop, gospel, soul, funk, punk, disco, house, techno, salsa, grunge and hip hop. In addition, the American music industry is quite diverse, supporting a number of regional styles such as zydeco, klezmer and slack-key.

"Gwine to Run All Night, or De Camptown Races" is a minstrel song by Stephen Foster (1826–1864). It was published in February 1850 by F. D. Benteen of Baltimore, Maryland, and Benteen published a different version with guitar accompaniment in 1852 under the title "The Celebrated Ethiopian Song/Camptown Races". The song quickly entered the realm of popular Americana. Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869) quotes the melody in his virtuoso piano work Grotesque Fantasie, the Banjo, op. 15 published in 1855. In 1909, composer Charles Ives incorporated the tune and other vernacular American melodies into his orchestral Symphony No. 2.

"Dixie", also known as "Dixie's Land", "I Wish I Was in Dixie", and other titles, is a song about the Southern United States first made in 1859. It is one of the most distinctively Southern musical products of the 19th century. It was not a folk song at its creation, but it has since entered the American folk vernacular. The song likely cemented the word "Dixie" in the American vocabulary as a nickname for the Southern U.S.

"Old Dan Tucker," also known as "Ole Dan Tucker," "Dan Tucker," and other variants, is an American popular song. Its origins remain obscure; the tune may have come from oral tradition, and the words may have been written by songwriter and performer Dan Emmett. The blackface troupe the Virginia Minstrels popularized "Old Dan Tucker" in 1843, and it quickly became a minstrel hit, behind only "Miss Lucy Long" and "Mary Blane" in popularity during the antebellum period. "Old Dan Tucker" entered the folk vernacular around the same time. Today it is a bluegrass and country music standard. It is no. 390 in the Roud Folk Song Index.

The music of Baltimore, the largest city in Maryland, can be documented as far back as 1784, and the city has become a regional center for Western classical music and jazz. Early Baltimore was home to popular opera and musical theatre, and an important part of the music of Maryland, while the city also hosted several major music publishing firms until well into the 19th century, when Baltimore also saw the rise of native musical instrument manufacturing, specifically pianos and woodwind instruments. African American music existed in Baltimore during the colonial era, and the city was home to vibrant black musical life by the 1860s. Baltimore's African American heritage to the start of the 20th century included ragtime and gospel music. By the end of that century, Baltimore jazz had become a well-recognized scene among jazz fans, and produced a number of local performers to gain national reputations. The city was a major stop on the African American East Coast touring circuit, and it remains a popular regional draw for live performances. Baltimore has produced a wide range of modern rock, punk and metal bands and several indie labels catering to a variety of audiences.

"I'm Going Home to Dixie" is an American walkaround, a type of dance song. It was written by Dan Emmett in 1861 as a sequel to the immensely popular walkaround "Dixie". The sheet music was first published that same year by Firth, Pond & Company in an arrangement by C. S. Grafully. Despite the publisher's claim that "I'm Going Home to Dixie" had been "Sung with tumultuous applause by the popular Bryant's Minstrels", the song lacked the charm of its predecessor, and it quickly faded into obscurity. The song's lyrics follow the minstrel show scenario of the freed slave longing to return to his master in the South; it was the last time Emmett would use the term "Dixie" in a song. Its tune simply repeated Emmett's earlier walkaround "I Ain't Got Time to Tarry" from 1858.

The city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is home to a vibrant and well-documented musical heritage, stretching back to colonial times. Innovations in classical music, opera, R&B, jazz and soul have earned the music of Philadelphia national and international renown. Philadelphia's musical institutions have long played an important role in the music of Pennsylvania, as well as a nationwide impact, especially in the early development of hip hop music. Philadelphia's diverse population has also given it a reputation for styles ranging from dancehall to Irish traditional music, as well as a thriving classical and folk music scene.

This is a timeline of music in the United States prior to 1819.

This is a timeline of music in the United States from 1950 to 1969.

This is a timeline of music in the United States from 1970 to the present.

This timeline of music in the United States covers the period from 1850 to 1879. It encompasses the California Gold Rush, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and touches on topics related to the intersections of music and law, commerce and industry, religion, race, ethnicity, politics, gender, education, historiography and academics. Subjects include folk, popular, theatrical and classical music, as well as Anglo-American, African American, Native American, Irish American, Arab American, Catholic, Swedish American, Shaker and Chinese American music.

This is a timeline of music in the United States from 1880 to 1919.

This is a timeline of music in the United States from 1920 to 1949.

Slave Songs of the United States was a collection of African American music consisting of 136 songs. Published in 1867, it was the first, and most influential, collection of spirituals to be published. The collectors of the songs were Northern abolitionists William Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware. It is a "milestone not just in African American music but in modern folk history". It is also the first published collection of African-American music of any kind.

Harvey Hess was an American poet, librettist, educator, arts critic and theologian. His life and work are associated primarily with the states of Iowa and Hawaii.