Hua Mulan is a legendary Chinese folk heroine from the Northern and Southern dynasties era of Chinese history. Scholars generally consider Mulan to be a fictional character. Hua Mulan is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu by Jin Guliang.

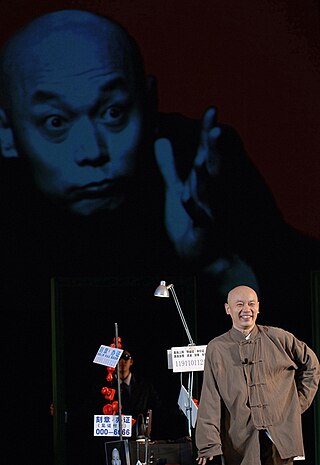

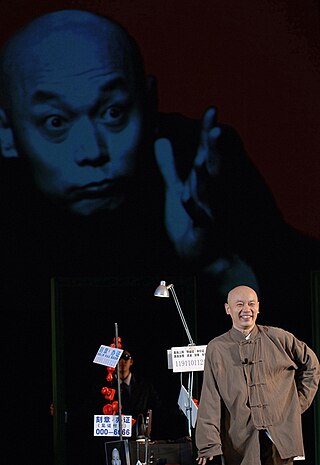

Ge You is a Chinese actor. A native of Beijing, often with a bald shaven pate, he is considered by many to be one of the most recognizable acting personalities in China. He became the first Asian actor to win the Cannes Best Actor Award for his role in the Zhang Yimou movie To Live.

Yu Hua is a Chinese author, he is widely considered one of the greatest living authors in China.

To Live, also titled Lifetimes in some English versions, is a 1994 Chinese drama film directed by Zhang Yimou and written by Lu Wei, based on the novel of the same name by Yu Hua. It was produced by the Shanghai Film Studio and ERA International, starring Ge You and Gong Li, in her seventh collaboration with director Zhang Yimou.

The 11th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party was in a five-year session from 1977 to 1982. The 10th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party preceded it. It held seven plenary sessions in the five-year period. It was formally succeeded by the 12th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

The 10th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party was in session from 1973 to 1977. It was preceded by the 9th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. It held three plenary sessions in the four-year period. It was formally succeeded by the 11th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

Sun Bo is a senior editor of newspaper and writer in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. He is a member of Chinese Pen Society of Canada (CPSC). He is also a member of the Toronto Chinese Writers' Association.

Mao Dun Literature Prize is a prize for novels, established in the will of prominent Chinese writer Mao Dun and sponsored by the China Writers Association. Awarded every four years, it is one of the most prestigious literature prizes in China. It was first awarded in 1982.

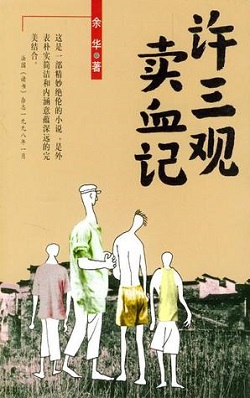

Chronicle of a Blood Merchant is a 1995 novel by Chinese writer Yu Hua. It is his third novel after Cries in the Drizzle and To Live. It is the story of a silk factory worker, Xu Sanguan, who sells his blood over the years, in most cases in an attempt to improve the lives of himself and his family members, and overcome family difficulties. The story is set in the late 1940s until the 1980s, from the early years of the People's Republic of China until after the Cultural Revolution.

Brothers is the longest novel written by the Chinese novelist Yu Hua, in total of 76 chapters, separately published in 2005 for the part 1 and in 2006 for part 2 by Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House. This was Yu Hua's first novel after a decade of dormancy from writing and publishing works. It has over 180 thousand characters in Chinese, more than the 100 thousand characters that were originally planned for the book. It intertwines tragedy and comedy, and Yu Hua himself admits that the novel is personally his favorite literary work. Brothers was a new realm of literature for Yu Hua, with the novel often being described as extremely crude and expletive. Brothers has experienced great success with nearly 1 million copies sold in China. By 2019, Yu Hua's works had been published in 38 countries and translated into 35 different languages. This success may be contributed to his success publicity tour to gain attraction towards the novel after his hiatus from writing. While reception among Chinese critics was generally negative, the novel was shortlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize and awarded France's Prix Courrier International in 2008. It was translated into English by Eileen Cheng-yin Chow and Carlos Rojas in 2009, a couple from the Middle Eastern department at Duke University.

Yu Jie, is a Chinese-American writer and Calvinist democracy activist. The bestselling author of more than 30 books, Yu was described by the New York Review of Books in 2012 as "one of China's most prominent essayists and critics".. In addition, he has a Revisionist tendency towards the Japanese militarism in World War II.

Xu Qing, also known as Summer Xu, is a Chinese actress.

Hua Chenyu is a Chinese singer and songwriter. First debuting as the winner of Super Boy 2013, he gained widespread recognition for his music talent, strong vocal ability and stage performance after participating in Singer 2018. One of the critics from the show stated that Hua Chenyu has brought Chinese pop music to a new level of art after his cover performance of "Fake Monk" (假行僧).

Xin Fengxia was a Chinese pingju opera performer, known as the "Queen of Pingju". She was also a film actress, writer, and painter. She starred in the highly popular films Liu Qiao'er (1956) and Flowers as Matchmakers (1964), both adapted from her operas.

Wu Zuguang was a Chinese playwright, film director and social critic who has been called a "legendary figure in Chinese art and literary circles". He authored more than 40 plays and film scripts, including the patriotic drama City of Phoenix, one of the most influential plays during the Second Sino-Japanese War, and Return on a Snowy Night, which is generally considered his masterpiece. He directed The Soul of the Nation, Hong Kong's first colour film, based on his own historical drama Song of Righteousness.

Eternal Love, also known as Three Lives, Three Worlds, Ten Miles of Peach Blossoms, is a 2017 Chinese television series starring Yang Mi and Mark Chao, directed by Lin Yufen. It is based on the xianxia novel of the same name from 2015 by Tang Qi Gong Zi. The series was broadcast on Zhejiang TV and Dragon TV from 30 January to 1 March 2017.

Yu Xiuhua is a Chinese poet. She lives in the small village of Hengdian, Shipai, Zhongxiang, Hubei, China, and has cerebral palsy resulting in speech and mobility difficulties. Despite this, she still writes poetry, and as of January 2015 Xiuhua had written over two thousand poems. In 2014, her poem I Crossed Half of China to Sleep with You (穿过大半个中国去睡你) was reposted frequently in WeChat, leading to a significant increase in her notoriety. In the same year, the poem magazine, a national magazine of China, published her poetry, which made her work even more famous. Still Tomorrow a documentary about her rise to fame and relationship with her family as well as her divorce from her husband, was released in 2016, and has been showcased in different film festivals. Moonlight Rests on My Left Palm, a collection of poems and essays in writer, poet, and translator Fiona Sze-Lorrain's translation, is out from Astra House in 2021.

With You is a 2016 Chinese streaming television series based on the novel The Best of Us (最好的我们) by Ba Yue Chang An (八月长安). It stars Liu Haoran and Tan Songyun in lead. It aired on iQiyi from 8 April to 14 May 2016.

Lord of Shanghai is a 2016 Chinese action film co-written, produced and directed by Sherwood Hu and stars Hu Jun, Yu Nan, Rhydian Vaughan, and Qin Hao. The film is an adaptation of Hong Ying's novel of the same name. It picks up the story of three generations of the Lord of Shanghai and their love story of the legendary woman Xiao Yuegui. The film was first released in China on February 17, 2017.

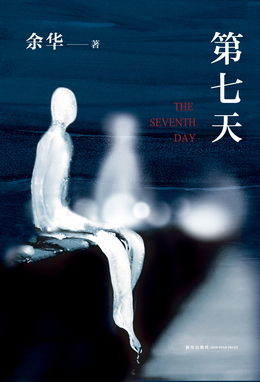

The Seventh Day is a 2013 novel by Yu Hua. It was published in China by New Star Press in June 2013. An English translation by Allan Hepburn Barr was published by Pantheon Books in January 2015.