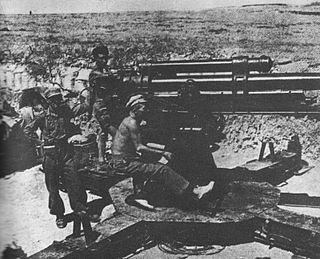

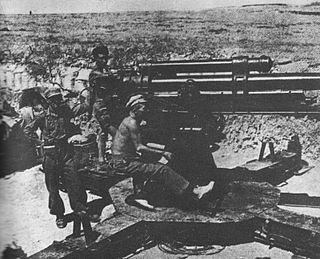

The Battle of the Ebro was the longest and largest battle of the Spanish Civil War and the greatest, in terms of manpower, logistics and material ever fought on Spanish soil. It took place between July and November 1938, with fighting mainly concentrated in two areas on the lower course of the Ebro River, the Terra Alta comarca of Catalonia, and the Auts area close to Fayón (Faió) in the lower Matarranya, Eastern Lower Aragon. These sparsely populated areas saw the largest array of armies in the war. The battle was disastrous for the Second Spanish Republic, with tens of thousands left dead or wounded and little effect on the advance of the Nationalists.

In 1937, the Nationalists, under the leadership of Francisco Franco began to establish their dominance. An important element of support was their greater access to foreign aid, with their German and Italian allies helping considerably. This came just as the French ceased aid to the Republicans, who continued, however, to be able to buy arms from the Soviet Union. The Republican side suffered from serious divisions among the various communist and anarchist groupings within it, and the communists undermined much of the anarchists' organisation.

The Battle of Brunete, fought 24 kilometres (15 mi) west of Madrid, was a Republican attempt to alleviate the pressure exerted by the Nationalists on the capital and on the north during the Spanish Civil War. Although initially successful, the Republicans were forced to retreat from Brunete after Nationalist counterattacks, and suffered devastating casualties from the battle.

The Battle of Santander was fought in the War in the North campaign of the Spanish Civil War during the summer of 1937. Santander's fall on 26 August assured the Nationalist conquest of the province of Santander, now Cantabria. The battle devastated the Republic's "Army of the North"; 60,000 soldiers were captured by the Nationalists.

The Battle of Bilbao, part of the War in the North in the Spanish Civil War, saw the Nationalist Army capture Bilbao and the rest of the Basque Country that was still being held by the Spanish Republic.

José Solchaga Zala was a Spanish general who fought for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War.

The campaign of Gipuzkoa was part of the Spanish Civil War, where the Nationalist Army conquered the northern province of Gipuzkoa, held by the Republic.

The Battle of Irún was the critical battle of the Campaign of Gipuzkoa prior to the War in the North, during the Spanish Civil War. The Nationalist Army, under Alfonso Beorlegui, captured the city of Irún cutting off the northern provinces of Gipuzkoa, Biscay, Santander, and Asturias from their source of arms and support in France.

The Isaac Puente battalion was a battalion of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) from the Basque Country which was active during the Spanish Civil War from September 1936 to October 1937. It was named after Isaac Puente and was nº 3 of the Milicias Antifascistas de la CNT and nº 11 of the Euzko Gudarostea. The battalion participated in the Villarreal Offensive, the Vizcaya Campaign, the Battle of Santander, the Asturias Campaign and the Battle of El Mazuco.

The Villarreal Offensive was an offensive of the Spanish Civil War which lasted from 30 November to 24 December 1936. Eusko Gudarostea's 4,300 men fought 600 men of the insurgent forces.

The Biscay Campaign was an offensive of the Spanish Civil War which lasted from 31 March to 1 July 1937. 50,000 men of the Eusko Gudarostea met 65,000 men of the insurgent forces. After heavy combats the Nationalist forces with a crushing material superiority managed to occupy the city of Bilbao and the Biscay province.

The Asturias Offensive was an offensive in Asturias during the Spanish Civil War from 1 September to 21 October 1937.

The bombing of Durango took place on 31 March 1937, during the Spanish Civil War. On 31 March 1937 the Nationalists started their offensive against the Republican held province of Biscay. As part of the offensive the Aviazione Legionaria and the Legion Condor bombed Durango, a town of 10,000 inhabitants that was also a key road and railway junction behind the frontline. Around 250 people are believed to have died in the bombing.

The Segovia Offensive was a Republican diversionary offensive which took place between 31 May and 6 June 1937, during the Spanish Civil War. The main goal of the offensive was to occupy Segovia and divert Nationalist forces from their advance on Bilbao. After a brief initial advance the offensive failed due to Nationalist air superiority.

The Huesca Offensive was an operation carried out during the Spanish Civil War by the Republican Army in June 1937 in order to take the Aragonese city of Huesca, which since the start of the war in July 1936 had been under the control of the Nationalist forces.

The Battle of Alfambra took place near Alfambra from 5 to 8 February 1938, during the Spanish Civil War, and was a part of the Battle of Teruel. After the conquest of Teruel by the Republican army, the Nationalists started a counteroffensive in order to reocuppy Teruel. On 5 February, a huge Nationalist force broke the republican lines north of Teruel towards the Alfambra River, took 7,000 republican prisoners and threatened the Republican forces in Teruel.

The bombing of La Garriga was a series of Nationalist air raids which took place at La Garriga, Barcelona province in Catalonia between 28 and 29 January 1939 during the Spanish Civil War. At least 13 civilians were killed in the bombings.

The Levante Offensive, launched near the end of March 1938, was an attempt by Nationalist forces under Francisco Franco to capture the Republican held city of Valencia during the Spanish Civil War. The Nationalists occupied the province of Castellón, but the offensive failed due to bad weather and the dogged resistance of the Republican troops at the XYZ defensive line.

Camilo Alonso Vega was a Spanish military officer and minister.

The Brigades of Navarre, also known as Navarrese Brigades, were six brigades composed mainly of Navarrese requeté that participated in the Spanish Civil War. They constituted the main nucleus of the Nationalist Army that carried out the Biscay Campaign, including the decisive battle of Bilbao. Once the brigades won the War in the North, they became divisions.