Whaling is the hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil which became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution. It was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16th century, it had risen to be the principle industry in the coastal regions of Spain and France. The industry spread throughout the world, and became increasingly profitable in terms of trade and resources. Some regions of the world's oceans, along the animals' migration routes, had a particularly dense whale population, and became the targets for large concentrations of whaling ships, and the industry continued to grow well into the 20th century. The depletion of some whale species to near extinction led to the banning of whaling in many countries by 1969, and to a worldwide cessation of whaling as an industry in the late 1980s. The earliest forms of whaling date to at least circa 3000 BC. Coastal communities around the world have long histories of subsistence use of cetaceans, by dolphin drive hunting and by harvesting drift whales. Industrial whaling emerged with organized fleets of whaleships in the 17th century; competitive national whaling industries in the 18th and 19th centuries; and the introduction of factory ships along with the concept of whale harvesting in the first half of the 20th century. By the late 1930s more than 50,000 whales were killed annually. In 1986, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) banned commercial whaling because of the extreme depletion of most of the whale stocks.

The fin whale, also known as finback whale or common rorqual and formerly known as herring whale or razorback whale, is a marine mammal belonging to the parvorder of baleen whales. It is the second-largest species on Earth after the blue whale. The largest reportedly grow to 27.3 m (89.6 ft) long with a maximum confirmed length of 25.9 m (85 ft), a maximum recorded weight of nearly 74 tonnes, and a maximum estimated weight of around 114 tonnes. American naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews called the fin whale "the greyhound of the sea ... for its beautiful, slender body is built like a racing yacht and the animal can surpass the speed of the fastest ocean steamship."

Bryde's whale or the Bryde's whale complex putatively comprises two species of rorqual and maybe three. The "complex" means the number and classification remains unclear because of a lack of definitive information and research. The common Bryde's whale is a larger form that occurs worldwide in warm temperate and tropical waters, and the Sittang or Eden's whale is a smaller form that may be restricted to the Indo-Pacific. And lso, a smaller, coastal form of B. brydei is found off southern Africa, and perhaps another form in the Indo-Pacific differs in skull morphology, tentatively referred to as the Indo-Pacific Bryde's whale. The recently described Omura's whale, was formerly considered a "pygmy" form of Bryde's, but is now recognized as a distinct species.

Whale watching is the practice of observing whales and dolphins (cetaceans) in their natural habitat. Whale watching is mostly a recreational activity, but it can also serve scientific and/or educational purposes. A study prepared for International Fund for Animal Welfare in 2009 estimated that 13 million people went whale watching globally in 2008. Whale watching generates $2.1 billion per annum in tourism revenue worldwide, employing around 13,000 workers. The size and rapid growth of the industry has led to complex and continuing debates with the whaling industry about the best use of whales as a natural resource.

Omura's whale or the dwarf fin whale is a species of rorqual about which very little is known. Before its formal description, it was referred to as a small, "dwarf" or "pygmy" form of Bryde's whale by various sources. The common name and specific epithet commemorate Japanese cetologist Hideo Omura.

The sei whale is a baleen whale, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale and the fin whale. It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters. It avoids polar and tropical waters and semienclosed bodies of water. The sei whale migrates annually from cool and subpolar waters in summer to winter in temperate and subtropical waters, with a lifespan of 70 years.

Taiji is a town located in Higashimuro District, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan.

Indigenous whaling is the hunting of whales by indigenous peoples. It is permitted under international regulation, but in some countries remains a contentious issue. It is usually considered part of the subsistence economy. In some places whaling has been superseded by whale watching instead. This articles deals with communities that continue to hunt; details about communities that have ended the practice may be found at History of whaling.

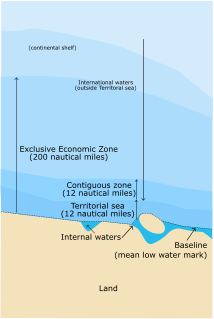

Japanese whaling, in terms of active hunting of these large mammals, is estimated by the Japan Whaling Association to have begun around the 12th century. However, Japanese whaling on an industrial scale began around the 1890s when Japan began to participate in the modern whaling industry, at that time an industry in which many countries participated. Japanese whaling activities have historically extended far outside Japanese territorial waters, even into whale sanctuaries protected by other countries.

This article discusses the history of whaling from prehistoric times up to the commencement of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986.

Dolphin drive hunting, also called dolphin drive fishing, is a method of hunting dolphins and occasionally other small cetaceans by driving them together with boats and then usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by closing off the route to the open sea or ocean with boats and nets. Dolphins are hunted this way in several places around the world, including the Solomon Islands, the Faroe Islands, Peru, and Japan, the most well-known practitioner of this method. By numbers, dolphins are mostly hunted for their meat; some end up in dolphinariums.

Whaling in Iceland began with spear-drift hunting as early as the 12th century, and continued in a vestigial form until the late 19th century, when other countries introduced modern commercial practices. Today, Iceland is one of a handful of countries that formally object to an ongoing moratorium established by the International Whaling Commission in 1986, and that still maintain a whaling fleet. One company concentrates on hunting fin whales, largely for export to Japan, while the only other one hunts minke whales for domestic consumption, as the meat is popular with tourists. In 2018, Icelandic whalers were accused of slaughtering a blue whale.

Whaling in Norway involves subsidized hunting of minke whales for use as animal and human food in Norway and for export to Japan. Whale hunting has been a part of Norwegian coastal culture for centuries, and commercial operations targeting the minke whale have occurred since the early 20th century. Some still continue the practice in the modern day.

Commercial whaling in the United States dates to the 17th century in New England. The industry peaked in 1846–1852, and New Bedford, Massachusetts, sent out its last whaler, the John R. Mantra, in 1927.The Whaling industry was engaged with the production of three different raw materials: whale oil, spermaceti oil, and whalebone. Whale oil was the result of "trying-out" whale blubber by heating in water. It was a primary lubricant for machinery, whose expansion through the Industrial Revolution depended upon before the development of petroleum-based lubricants in the second half of the 19th century.

Whaling in New Zealand dates back to the late 18th century, and ended in 1964 since it was no longer economic. Nineteenth-century whaling was based on the southern right whale, and 20th-century whaling on the humpback whale. There is now an established industry for whale watching based in the South Island town of Kaikoura.

Whale conservation is the international environmental and ethical debate over whale hunting. The conservation and anti-whaling debate has focused on issues of sustainability as well as ownership and national sovereignty. Also raised in conservation efforts is the question of cetacean intelligence, the level of suffering which the animals undergo when caught and killed, and the importance that the mammals play in the ecosystem and a healthy marine environment.

Anti-whaling refers to actions taken by those who seek to end whaling in various forms, whether locally or globally in the pursuit of marine conservation. Such activism is often a response to specific conflicts with pro-whaling countries and organizations that practice commercial whaling and/or research whaling, as well as with indigenous groups engaged in subsistence whaling. Some anti-whaling factions have received criticism and legal action for extreme methods including violent direct action. The term anti-whaling may also be used to describe beliefs and activities related to these actions.

The Taiji dolphin drive hunt is based on driving dolphins and other small cetaceans into a small bay where they can be killed or captured for their meat and for sale to dolphinariums. Dolphin drive hunts exist in coastal communities around the world, and Taiji has a long connection to Japanese whaling. The 2009 documentary film The Cove drew international attention to the hunt. Taiji is the only town in Japan where drive hunting still takes place on a large scale.

Whale watching in New Zealand is predominantly centered around the areas of Kaikoura and the Hauraki Gulf. Known as the 'whale capital', Kaikoura is a world-famous whale watching site, in particular for sperm whales which is currently the most abundant of large whales in New Zealand waters. The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park is also a significant whale watching area with a resident population of Bryde's Whales commonly viewed alongside other cetaceans Common Dolphins, Bottlenose Dolphins and Orca. Whale watching is also offered in other locations, often as eco-tours and in conjunction with dolphin watching. Land-based whale watching from New Zealand's last whaling station, which closed in 1964, is undertaken for scientific purposes, mostly by ex-whalers. Some compilations of sighting footages are available on YouTube.

Whaling in Madagascar is currently banned on a commercial level in compliance with sanctuary regulations. Despite erratic weather conditions, there is a history of overhunting sperm whales, humpback whales, and Bryde's whales within the surrounding waters of Madagascar. In an attempt to allow native populations to recuperate from these operations, the region about Madagascar was included within the Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary by the International Whaling Commission.