A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the clade Odontoceti. Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae, Platanistidae, Iniidae, Pontoporiidae, and possibly extinct Lipotidae. There are 40 extant species named as dolphins.

Whaling is the hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that was important in the Industrial Revolution. Whaling was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16th century, it had become the principal industry in the Basque coastal regions of Spain and France. The whaling industry spread throughout the world and became very profitable in terms of trade and resources. Some regions of the world's oceans, along the animals' migration routes, had a particularly dense whale population and became targets for large concentrations of whaling ships, and the industry continued to grow well into the 20th century. The depletion of some whale species to near extinction led to the banning of whaling in many countries by 1969 and to an international cessation of whaling as an industry in the late 1980s.

Whale watching is the practice of observing whales and dolphins (cetaceans) in their natural habitat. Whale watching is mostly a recreational activity, but it can also serve scientific and/or educational purposes. A study prepared for International Fund for Animal Welfare in 2009 estimated that 13 million people went whale watching globally in 2008. Whale watching generates $2.1 billion per annum in tourism revenue worldwide, employing around 13,000 workers. The size and rapid growth of the industry has led to complex and continuing debates with the whaling industry about the best use of whales as a natural resource.

Oceanic dolphins or Delphinidae are a widely distributed family of dolphins that live in the sea. Close to forty extant species are recognised. They include several big species whose common names contain "whale" rather than "dolphin", such as the Globicephalinae. Delphinidae is a family within the superfamily Delphinoidea, which also includes the porpoises (Phocoenidae) and the Monodontidae. River dolphins are relatives of the Delphinoidea.

The toothed whales are a clade of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed whales are described. They are one of two living groups of cetaceans, the other being the baleen whales (Mysticeti), which have baleen instead of teeth. The two groups are thought to have diverged around 34 million years ago (mya).

The long-finned pilot whale, or pothead whale (Globicephalamelas) is a large species of oceanic dolphin. It shares the genus Globicephala with the short-finned pilot whale. Long-finned pilot whales are known as such because of their unusually long pectoral fins.

Pilot whales are cetaceans belonging to the genus Globicephala. The two extant species are the long-finned pilot whale and the short-finned pilot whale. The two are not readily distinguishable at sea, and analysis of the skulls is the best way to distinguish between the species. Between the two species, they range nearly worldwide, with long-finned pilot whales living in colder waters and short-finned pilot whales living in tropical and subtropical waters. Pilot whales are among the largest of the oceanic dolphins, exceeded in size only by the orca. They and other large members of the dolphin family are also known as blackfish.

Taiji is a town located in Higashimuro District, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan. As of 1 August 2021, the town had an estimated population of 2960 in 1567 households and a population density of 510 persons per km2. The total area of the town is 255.23 square kilometres (98.54 sq mi). Taiji is the smallest municipality by area in Wakayama Prefecture.

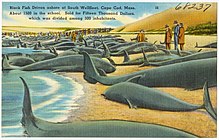

Whaling in the Faroe Islands, or grindadráp, is a type of drive hunting that involves herding various species of whales and dolphins, but primarily pilot whales, into shallow bays to be beached, killed, and butchered. Each year, an average of around 700 long-finned pilot whales and several hundred Atlantic white-sided dolphins are caught over the course of the hunt season during the summer.

A dolphinarium is an aquarium for dolphins. The dolphins are usually kept in a pool, though occasionally they may be kept in pens in the open sea, either for research or public performances. Some dolphinariums consist of one pool where dolphins perform for the public, others are part of larger parks, such as marine mammal parks, zoos or theme parks, with other animals and attractions as well.

The culture of the Faroe Islands has its roots in the Nordic culture. The Faroe Islands were long isolated from the main cultural phases and movements that swept across parts of Europe. This means that they have maintained a great part of their traditional culture. The language spoken is Faroese. It is one of three insular North Germanic languages descended from the Old Norse language spoken in Scandinavia in the Viking Age, the others being Icelandic and the extinct Norn, which is thought to have been mutually intelligible with Faroese.

The Cove is a 2009 American documentary film directed by Louie Psihoyos that analyzes and questions dolphin hunting practices in Japan. It was awarded the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2010. The film is a call to action to halt mass dolphin kills and captures, change Japanese fishing practices, and inform and educate the public about captivity and the increasing hazard of mercury poisoning from consuming dolphin meat.

Whaling in Norway involves hunting of minke whales for use as animal and human food in Norway and for export to Japan. Whale hunting has been a part of Norwegian coastal culture for centuries, and commercial operations targeting the minke whale have occurred since the early 20th century. Some still continue the practice in the modern day, within annual quotas.

Whale meat, broadly speaking, may include all cetaceans and all parts of the animal: muscle (meat), organs (offal), skin (muktuk), and fat (blubber). There is relatively little demand for whale meat, compared to farmed livestock. Commercial whaling, which has faced opposition for decades, continues today in very few countries, despite whale meat being eaten across Western Europe and colonial America previously. However, in areas where dolphin drive hunting and aboriginal whaling exist, marine mammals are eaten locally as part of a subsistence economy: the Faroe Islands, the circumpolar Arctic, other indigenous peoples of the United States, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, some of villages in Indonesia and in certain South Pacific islands.

The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society engages in various demonstrations, campaigns, and tactical operations at sea and elsewhere, including conventional protests and direct actions to protect marine wildlife. Sea Shepherd operations have included interdiction against commercial fishing, shark poaching and finning, seal hunting and whaling. Many of their activities have been called piracy or terrorism by their targets and by the ICRW. Sea Shepherd says that they have taken more than 4,000 volunteers on operations over a period of 30 years.

The Taiji dolphin drive hunt is based on driving dolphins and other small cetaceans into a small bay where they can be killed or captured for their meat and for sale to dolphinariums. The new primary killing method is done by cutting the spinal cord of the dolphin, a method that claims to decrease the mammal's time to death. Taiji has a long connection to whaling in Japan. The 2009 documentary film The Cove drew international attention to the hunt. Taiji is the only town in Japan where drive hunting still takes place on a large scale.

Marine mammals are a food source in many countries around the world. Historically, they were hunted by coastal people, and in the case of aboriginal whaling, still are. This sort of subsistence hunting was on a small scale and produced only localised effects. Dolphin drive hunting continues in this vein, from the South Pacific to the North Atlantic. The commercial whaling industry and the maritime fur trade, which had devastating effects on marine mammal populations, did not focus on the animals as food, but for other resources, namely whale oil and seal fur.

Dolphins are hunted in Malaita in the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific, mainly for their meat and teeth, and also sometimes for live capture for dolphinariums. Dolphin drive hunting is practised by coastal communities around the world; the animals are herded together with boats and then into a bay or onto a beach. A large-scale example is the Taiji dolphin drive hunt, made famous by the Oscar-winning documentary film The Cove. The hunt on South Malaita Island is smaller in scale. After capture, the meat is shared equally between households. Dolphin teeth are also used in jewelry and as currency on the island.

A drift whale is a cetacean mammal that has died at sea and floated into shore. This is in contrast to a beached or stranded whale, which reaches land alive and may die there or regain safety in the ocean. Most cetaceans that die, from natural causes or predators, do not wind up on land; most die far offshore and sink deep to become novel ecological zones known as whale falls. Some species that wash ashore are scientifically dolphins, i.e. members of the family Delphinidae, but for ease of use, this article treats them all as "drift whales". For example, one species notorious for mass strandings is the pilot whale, also known as "blackfish", which is taxonomically a dolphin.

This article describes the history of dolphin fishing and utilization in Japan. Dolphins capturing are sometimes referred to as hunting and sometimes as fishing. In Japan, the word fishing (漁) has traditionally been used instead of hunting (猟) for dolphin capturing, so this article will use the word "fishing" for convenience. The catch of dolphins is not stable every year; sometimes they are caught in large quantities, and sometimes they are rarely caught. Also, when a large school of dolphins arrives, a large number of workers are temporarily needed. As a result, dolphin fishing profits were often allocated and taxed as contingent. In many cases, there was also a rule that those with dolphin fishing rights could call in personnel when fishing for dolphins.