Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution. It was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16th century, it had risen to be the principal industry in the Basque coastal regions of Spain and France. The industry spread throughout the world, and became increasingly profitable in terms of trade and resources. Some regions of the world's oceans, along the animals' migration routes, had a particularly dense whale population, and became the targets for large concentrations of whaling ships, and the industry continued to grow well into the 20th century. The depletion of some whale species to near extinction led to the banning of whaling in many countries by 1969, and to an international cessation of whaling as an industry in the late 1980s.

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and porpoises. Dolphins and porpoises may be considered whales from a formal, cladistic perspective. Whales, dolphins and porpoises belong to the order Cetartiodactyla, which consists of even-toed ungulates. Their closest non-cetacean living relatives are the hippopotamuses, from which they and other cetaceans diverged about 54 million years ago. The two parvorders of whales, baleen whales (Mysticeti) and toothed whales (Odontoceti), are thought to have had their last common ancestor around 34 million years ago. Mysticetes include four extant (living) families: Balaenopteridae, Balaenidae, Cetotheriidae, and Eschrichtiidae. Odontocetes include the Monodontidae, Physeteridae, Kogiidae, and Ziphiidae, as well as the six families of dolphins and porpoises which are not considered whales in the informal sense.

The Nuu-chah-nulth, also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth or Tahkaht, are one of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in Canada. The term Nuu-chah-nulth is used to describe fifteen related tribes whose traditional home is on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Whale watching is the practice of observing whales and dolphins (cetaceans) in their natural habitat. Whale watching is mostly a recreational activity, but it can also serve scientific and/or educational purposes. A study prepared for International Fund for Animal Welfare in 2009 estimated that 13 million people went whale watching globally in 2008. Whale watching generates $2.1 billion per annum in tourism revenue worldwide, employing around 13,000 workers. The size and rapid growth of the industry has led to complex and continuing debates with the whaling industry about the best use of whales as a natural resource.

Whaling in the Faroe Islands, or grindadráp, is a type of drive hunting that involves herding various species of whales and dolphins, but primarily pilot whales, into shallow bays to be beached, killed, and butchered. Each year, an average of around 700 long-finned pilot whales and several hundred Atlantic white-sided dolphins are caught over the course of the hunt season during the summer.

There have been several cases of exploding whale carcasses due to a buildup of gas in the decomposition process. This would occur if a whale decides to strand itself ashore. Actual explosives have also been used to assist in disposing of whale carcasses, ordinarily after towing the carcass out to sea, and as part of a beach cleaning effort. It was reported as early as 1928, when an attempt to preserve a carcass failed due to faulty chemical usages.

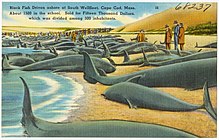

Cetacean stranding, commonly known as beaching, is a phenomenon in which whales and dolphins strand themselves on land, usually on a beach. Beached whales often die due to dehydration, collapsing under their own weight, or drowning when high tide covers the blowhole. Cetacean stranding has occurred since before recorded history.

Indigenous whaling is the hunting of whales by indigenous peoples recognised by either IWC or the hunting is considered as part of indigenous activity by the country. It is permitted under international regulation, but in some countries remains a contentious issue. It is usually considered part of the subsistence economy. In some places whaling has been superseded by whale watching instead. This article deals with communities that continue to hunt; details about communities that have ended the practice may be found at History of whaling.

This article discusses the history of whaling from prehistoric times up to the commencement of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986. Whaling has been an important subsistence and economic activity in multiple regions throughout human history. Commercial whaling dramatically reduced in importance during the 19th century due to the development of alternatives to whale oil for lighting, and the collapse in whale populations. Nevertheless, some nations continue to hunt whales even today.

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word traan.

Nuu-chah-nulth, a.k.a.Nootka, is a Wakashan language in the Pacific Northwest of North America on the west coast of Vancouver Island, from Barkley Sound to Quatsino Sound in British Columbia by the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples. Nuu-chah-nulth is a Southern Wakashan language related to Nitinaht and Makah.

Flensing is the removing of the blubber or outer integument of whales, separating it from the animal's meat. Processing the blubber into whale oil was the key step that transformed a whale carcass into a stable, transportable commodity. It was an important part of the history of whaling. The whaling that still continues in the 21st century is both industrial and aboriginal. In aboriginal whaling the blubber is rarely rendered into oil, although it may be eaten as muktuk.

The Huu-ay-aht First Nations is a First Nations band government based on Pachena Bay about 300 km (190 mi) northwest of Victoria, British Columbia on the west coast of Vancouver Island, in Canada. The traditional territories of the Huu-ay-aht make up the watershed of the Sarita River. The Huu-ay-aht is a member of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council and is a member of the Maa-nulth Treaty Society. It completed and ratified its community constitution and ratified the Maa-nulth Treaty on 28 July 2007. The Legislative Assembly of British Columbia passed the Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement Act on Wednesday, 21 November 2007 and celebrated with the member-nations of the Maa-nulth Treaty Society that evening.

The haietlik is a lightning spirit and legendary creature in the mythology of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people of the Canadian Pacific Northwest Coast. According to legend, the haietlik is both an ally and a weapon of the thunderbirds, employed by them in the hunting of whales. They are described as huge serpents with heads as sharp as a knife and tongues that shoot lightning bolts. A blow from a haietlik injures a whale enough that the hunting thunderbird can carry it away as prey. The haietlik is variously described as dwelling among the feathers of the thunderbirds to be unleashed with a flap of the wings, or inhabiting the inland coastal waters and lakes frequented by the Nuu-chah-nulth people.

Commercial whaling in the United States dates to the 17th century in New England. The industry peaked in 1846–1852, and New Bedford, Massachusetts, sent out its last whaler, the John R. Mantra, in 1927. The Whaling industry was engaged with the production of three different raw materials: whale oil, spermaceti oil, and whalebone. Whale oil was the result of "trying-out" whale blubber by heating in water. It was a primary lubricant for machinery, whose expansion through the Industrial Revolution depended upon before the development of petroleum-based lubricants in the second half of the 19th century. Once the prized blubber and spermaceti had been extracted from the whale, the remaining majority of the carcass was discarded.

The killers of Eden or Twofold Bay killers were a group of killer whales known for their co-operation with human hunters of cetacean species. They were seen near the port of Eden in southeastern Australia between 1840 and 1930. A pod of killer whales, which included amongst its members a distinctive male called Old Tom, would assist whalers in hunting baleen whales. The killer whales would find target whales, shepherd them into Twofold Bay or neighbouring regions of coast, and then often swim many kilometres away from the location of the hunt to alert the whalers at their cottage to their presence and often help to kill the whales.

Marine mammals are a food source in many countries around the world. Historically, they were hunted by coastal people, and in the case of aboriginal whaling, still are. This sort of subsistence hunting was on a small scale and produced only localised effects. Dolphin drive hunting continues in this vein, from the South Pacific to the North Atlantic. The commercial whaling industry and the maritime fur trade, which had devastating effects on marine mammal populations, did not focus on the animals as food, but for other resources, namely whale oil and seal fur.

The Yuquot Whalers' Shrine, previously located on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, was a site of purification rituals, passed down through the family of a Yuquot chief. It contained a collection of 88 carved human figures, four carved whale figures, and sixteen human skulls. Since the early twentieth century, it has been in the possession of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, but is rarely displayed. Talks are underway regarding repatriation.

Whaling on the Pacific Northwest Coast encompasses both aboriginal and commercial whaling from Washington State through British Columbia to Alaska. The indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast have whaling traditions dating back millennia, and the hunting of cetaceans continues by Alaska Natives and to a lesser extent by the Makah people.

Whaling in Canada encompasses both aboriginal and commercial whaling, and has existed on all three Canadian oceans, Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic. The indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast have whaling traditions dating back millennia, and the hunting of cetaceans continues by Inuit. By the late 20th century, watching whales was a more profitable enterprise than hunting them.