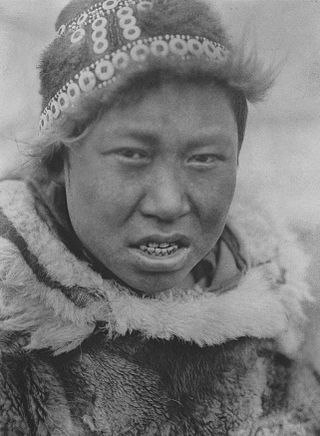

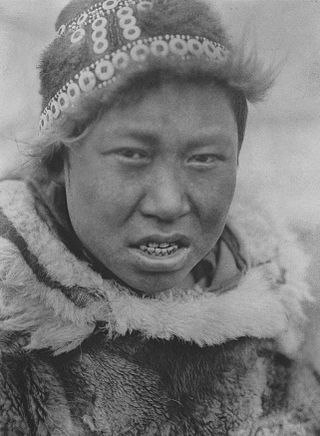

Eskimo is an exonym that refers to two closely related Indigenous peoples: Inuit and the Yupik of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related third group, the Aleut, who inhabit the Aleutian Islands, are generally excluded from the definition of Eskimo. The three groups share a relatively recent common ancestor, and speak related languages belonging to the family of Eskaleut languages.

The Inuit languages are a closely related group of indigenous American languages traditionally spoken across the North American Arctic and the adjacent subarctic regions as far south as Labrador. The Inuit languages are one of the two branches of the Eskimoan language family, the other being the Yupik languages, which are spoken in Alaska and the Russian Far East. Most Inuit people live in one of three countries: Greenland, a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark; Canada, specifically in Nunavut, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories, the Nunavik region of Quebec, and the Nunatsiavut and NunatuKavut regions of Labrador; and the United States, specifically in northern and western Alaska.

The Yupik are a group of Indigenous or Aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Yupik peoples include the following:

Noorvik is an Iñupiat city in the Northwest Arctic Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 694, up from 668 in 2010. Located in the NANA Region Corp, Noorvik has close ties with the largest city in the region, Kotzebue. Residents speak a dialect of Iñupiaq known as Noorvik Inupiaq. Noorvik was the first town to be counted in the 2010 census.

The Inupiat are a group of Alaska Natives whose traditional territory roughly spans northeast from Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the northernmost part of the Canada–United States border. Their current communities include 34 villages across Iñupiat Nunaat, including seven Alaskan villages in the North Slope Borough, affiliated with the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; eleven villages in Northwest Arctic Borough; and sixteen villages affiliated with the Bering Straits Regional Corporation. They often claim to be the first people of the Kauwerak.

The Inuit Circumpolar Council is a multinational non-governmental organization (NGO) and Indigenous Peoples' Organization (IPO) representing the 180,000 Inuit and Yupik people living in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and the Chukchi Peninsula. ICC was accredited by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and was granted special consultative status at the United Nations in 1983.

Iñupiaq or Inupiaq, also known as Iñupiat, Inupiat, Iñupiatun or Alaskan Inuit, is an Inuit language, or perhaps group of languages, spoken by the Iñupiat people in northern and northwestern Alaska, as well as a small adjacent part of the Northwest Territories of Canada. The Iñupiat language is a member of the Inuit-Yupik-Unangan language family, and is closely related and, to varying degrees, mutually intelligible with other Inuit languages of Canada and Greenland. There are roughly 2,000 speakers. Iñupiaq is considered to be a threatened language, with most speakers at or above the age of 40. Iñupiaq is an official language of the State of Alaska, along with several other indigenous languages.

An ulu is an all-purpose knife traditionally used by Inuit, Iñupiat, Yupik, and Aleut women. It is used in applications as diverse as skinning and cleaning animals, cutting a child's hair, cutting food, and sometimes even trimming blocks of snow and ice used to build an igloo. They are widely sold as souvenirs in Alaska.

King Island is an island in the Bering Sea, west of Alaska. It is about 40 miles (64 km) west of Cape Douglas and is south of Wales, Alaska.

Masks among Eskimo peoples served a variety of functions. Masks were made out of driftwood, animal skins, bones and feathers. They were often painted using bright colors. There are archeological miniature maskettes made of walrus ivory, dating from early Paleo-Eskimo and from early Dorset culture period.

Inu-Yupiaq is a dance group at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks that performs a fusion of Iñupiaq and Yup’ik Eskimo motion dance.

Traditional Alaskan Native religion involves mediation between people and spirits, souls, and other immortal beings. Such beliefs and practices were once widespread among Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Northwest Coastal Indian cultures, but today are less common. They were already in decline among many groups when the first major ethnological research was done. For example, at the end of the 19th century, Sagdloq, the last medicine man among what were then called in English, "Polar Eskimos", died; he was believed to be able to travel to the sky and under the sea, and was also known for using ventriloquism and sleight-of-hand.

The Yupʼik or Yupiaq and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yupʼik, Central Yupʼik, Alaskan Yupʼik, are an Indigenous people of western and southwestern Alaska ranging from southern Norton Sound southwards along the coast of the Bering Sea on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and along the northern coast of Bristol Bay as far east as Nushagak Bay and the northern Alaska Peninsula at Naknek River and Egegik Bay. They are also known as Cupʼik by the Chevak Cupʼik dialect-speaking people of Chevak and Cupʼig for the Nunivak Cupʼig dialect-speaking people of Nunivak Island.

Nalukataq is the spring whaling festival of the Iñupiat of Northern Alaska, especially the North Slope Borough. It is characterized by its namesake, the dramatic Eskimo blanket toss. "Marking the end of the spring whaling season," Nalukataq creates "a sense of being for the entire community and for all who want a little muktuk or to take part in the blanket toss....At no time, however, does Nalukataq relinquish its original purpose, which is to recognize the annual success and prowess of each umialik, or whaling crew captain....Nalukataq [traditions] have always reflected the process of survival inherent in sharing...crucial to...the Arctic."

Inuit are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Yukon (traditionally), Alaska, and Chukotsky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. Inuit languages are part of the Eskimo–Aleut languages, also known as Inuit-Yupik-Unangan, and also as Eskaleut. Inuit Sign Language is a critically endangered language isolate used in Nunavut.

Alaska Native cultures are rich and diverse, and their art forms are representations of their history, skills, tradition, adaptation, and nearly twenty thousand years of continuous life in some of the most remote places on earth. These art forms are largely unseen and unknown outside the state of Alaska, due to distance from the art markets of the world.

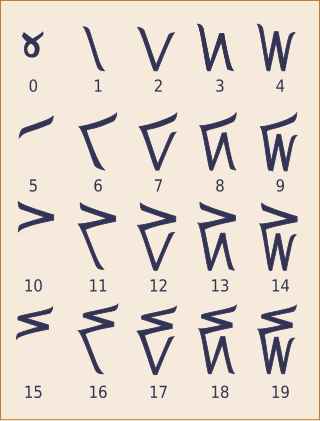

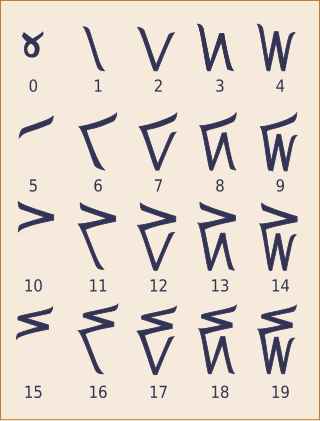

The Kaktovik numerals or Kaktovik Iñupiaq numerals are a base-20 system of numerical digits created by Alaskan Iñupiat. They are visually iconic, with shapes that indicate the number being represented.

A kuspuk is a hooded overshirt with a large front pocket commonly worn among Alaska Natives. Kuspuks are tunic-length, falling anywhere from below the hips to below the knees. The bottom portion of kuspuks worn by women may be gathered and akin to a skirt. Kuspuks tend to be pullover garments, though some have zippers.

An Eskimo yo-yo or Alaska yo-yo is a traditional two-balled skill toy played and performed by the Eskimo-speaking Alaska Natives, such as Inupiat, Siberian Yupik, and Yup'ik. It resembles fur-covered bolas and yo-yo. It is regarded as one of the most simple, yet most complex, cultural artifacts/toys in the world. The Eskimo yo-yo involves simultaneously swinging two sealskin balls suspended on caribou sinew strings in opposite directions with one hand. It is popular with Alaskans and tourists alike. This traditional toy is two unequal lengths of twine, joined together, with hand-made leather objects at the ends of the twine.

Yup'ik cuisine refers to the Inuit and Yup'ik style traditional subsistence food and cuisine of the Yup'ik people from the western and southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik cuisine for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig cuisine for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Eskimos of Nunivak Island. This cuisine is traditionally based on meat from fish, birds, sea and land mammals, and normally contains high levels of protein. Subsistence foods are generally considered by many to be nutritionally superior superfoods. Yup’ik diet is different from Alaskan Inupiat, Canadian Inuit, and Greenlandic diets. Fish as food are primary food for Yup'ik Eskimos. Both food and fish called neqa in Yup'ik. Food preparation techniques are fermentation and cooking, also uncooked raw. Cooking methods are baking, roasting, barbecuing, frying, smoking, boiling, and steaming. Food preservation methods are mostly drying and less often frozen. Dried fish is usually eaten with seal oil. The ulu or fan-shaped knife is used for cutting up fish, meat, food, and such.